Ching-chih Chen

Graduate School of Library & Information Science

Simmons College

Boston, MA 02115, USA

E-Mail: CCHEN@VMSVAX.SIMMONS.EDU

Abstracts: A brief overview on the recent technological development in the area of multi-media technologies to enhance information access. Topics covered include optical techno-logies, digital technologies and their interactive multimedia applications, as well as the current media-mixed information provision environment. Implications of these technolo-gies in enhancing information access and provisions will be discussed. The changing role of information specialists in this visual digital information age will also be articulated.

In every area of information technology -- computing, communications, and content -- there has been tremendous development over the last decade. In the area of computing, we have watched: the advent of personal computers, worldwide packet networks, new information technologies such as optical disc and other mass storage media, interactive video, electronic imaging, computer graphic, scanning and digitizing, voice, animation, communications, and multimedia/hypermedia. In the area of content, we have witnessed the growth both in size and in number of massive public and private databases -- bibliographic first, then numeric, and now multimedia. In the area of communications, there has been enormous development in electronic digital communications via which we hope to be able to transmit multimedia information worldwide at an incredible speed. Computing, communica-tions, and content were rather disparate in earlier years, but are becoming increasingly integrated and quite international in scope and impact. In addition, we have also seen the convergence of all these new information technologies with conventional media. This is why we are witnessing the conver-gence of professional activities of all types of information professionals.

In the previous decade, delivery of multimedia information was only possible in a limited way. Most computer information systems were almost exclusively textual and numeric in nature. Yet, in this current information environment, our information seekers are no longer satisfied with only print-based information. Advances in multimedia technologies make it possible now for us to provide instant information access to any type of information one desires -- text, data, still image, motion picture, and sound. Thus, we have entered into this "digital" "visual" and "multimedia" information age, information landscape has become much more interesting and complex, and consequently our work as information professionals are much more challenging, difficult, but also exciting and rewarding.

With the above as a preface, this paper will attempt to cover multimedia, information network, and the new opportunities and problems/issues for information access and sharing.

2. WHAT IS MULTIMEDIA/HYPERMEDIA?

In Vannevar Bush's famous article entitled "As we may think" published in the July 1945 issue of Atlantic Monthly, he projected that "information overload" would be a serious problem. It would be increasingly difficult for one to keep up with the latest knowledge in any given field. He then described his vision of a device called "Memex," an electronic disk that could access any text of linking files within seconds. Although Memex was never actually developed, the foundation for a system now known as hypertext was laid. Bush's idea inspired two people about 20 years later -- Douglas C. Englebart of the Stanford Research Institute and Ted Nelson of Xanadu. In the 1960s Nelson coined the word "hypertext," which he describes as a non-sequential reading and writing that links different nodes of the text.

Various experiments on the development of hypertext applications and systems took place in the following decade, followed by the introduction of a few commercial products and tools, such as Guide by Owl. Yet, it is generally accepted that the hypermedia and multimedia applications have exploded only since Apple introduced its incredibly cheap but powerful HyperCard™ in the last quarter of 1987. Space limitation prevents me from presenting a detailed discussion on the develop-ment of hypertext and hypermedia beyond this brief mention.

However, in order to facilitate our later discussion on online multimedia/hypermedia information seeking and provision, I have provided a simple working definition of "multimedia/ hypermedia":

Since the introduction of HyperCard™, each year has been considered as one of the most signi-ficant years for the development of multimedia technologies. There have been so many significant advances related to various components of multimedia technologies -- computer processing, image processing, optical storage technologies (including CD-ROM, analog videodisc, WORM, and erasable), display technologies, digital audio, consumer electronics, telecommunications, scanning, digitized video technologies, desk-top video technology, etc. All have contributed greatly to the development of multimedia applications.

For example, in the optical technology area, there are so many different types of media (Figure 1). They include:

CD-ROM Photo CD

CD-ROM XA (eXtended Architecture) CD-WORM

CD-I (Compact Disc-Interactive) Videodisc

DVI (Digital Video Interactive) Erasable

CD-TV

While all of them share some common features, such as large storage capacity, quick random access, portability, durability, etc..., they differ from each other as well in functionalities. When integrated with computerized information systems, they can be powerful tools to provide incredibly powerful solutions to information related problems. Time does not permit discussion of each of the optical media. Brief mention to a few of them serves to illustrate the great potential of these techno-logies.

CD-ROM

In the CD-ROM technology area, the rate of increase in both the number of drives installed and the number of CD-ROM products available continue to grow steadily and fast. The market platform for CD-ROM with an installed base of only 171,000 drives in 1988, has already reached more than 2 million drives now. Many early obstacles to acceptance of CD-ROM technology, such as price, performance of drives, ability to daisy-chain the drives, etc..., have been lifted. Furthermore, the capability to do one's own desk-top CD-ROM publishing is in place, thanks to the powerful but low-cost software and peripherals below the price tag of $1,000, and the low reproductive cost, at $500 for the production of a 600-MB master discs with 10 copies, and each additional for only $1.50. Two students of mine were able to produce a CD-ROM with full-text access to over 2,000 pages of text and over 200 digital images in two month.

CD-ROM Jukebox

Now, high-end CD-ROM jukebox is also available to provide large networked full-image datbase access. Take the commercially available UMI's ProQuest MultiAccess System as an example, the CD-ROM jukebox is a significant component of an integrated information system. While the jukebox occupies less than 2 square feet of table space, it hold 240 discs with 600-MB of storage capacity for each of the discs. The 240 discs have the capacity to include 1.44 million full-page images. Up to sever such jukeboxes can be daisy-chained together to be connected to a system network, which can then deliver full-text and full-image document delivery over the network to system users in a few seconds.

CD-ROM XA, CDI, DVI, Photo CD, CD WORM, etc...

One step of pushing CD-ROM technology to areas of

multimedia is the introduction of CD-ROM Extended Architecture (CD-ROM

XA) by Microsoft and Sony in 1989. This standard enables the

inclusion of FM video on a standard CD-ROM. More advances also continue with DVI (Digital Video Interactive), CD-ROM XA (eXtended Architecture), CD-I (Compact Disc-Interactive), Photo CD, etc... While some are more for meeting wide-scale consumers' needs, such as CD-I and Photo CD products, others are more geared for industrial and academic use, such as DVI.

CD-I

Compact Disc Interactive (CD-I) is a new consumer multimedia product invented by Philips of the Netherlands and introduced in 1986. CD-I allows audio, video, and graphic materials to be stored simultaneously on the familiar CD format. The CD-I system is capable of handling a large amount of interrelated data in real time. The result is a combination of synchronized audio, video, and text information. The total disc capacity of CD-I is shared between the various types of inter-related audio or video data. A wide range of interactive effects and video images are available, including full motion, full screen video, scrolling and partial updates. For audios, it is possible to store 16 languages on a same disc, although from practical point of view, it is not commonly done.

DVI

Digital Video Interactive (DVI) technology combines interactivity and high-quality graphics with the presentation of full-color motion digital video, stills, and audio; all in an IBM compatible per-sonal computer. Since Intel shipped its first Pro750™ ADP Application Development Platform in mid 1989, it has been much easier for application developers to create interactive applications with full-screen/full-motion video, multiple-track audio, still video images, and dynamic graphics. Thus, broad and multimedia applications in a variety of markets, particularly in the industrial sector, have been introduced.

Photo CD

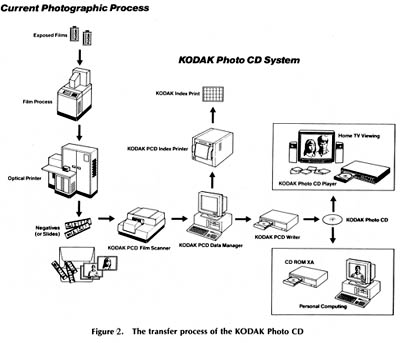

Building on audio CD technology, the Kodak Photo CD system transfers images captured on exposed and processed 35 mm film onto a writable CD in the process as shown in Figure 2. A dual-purpose photo/audio CD player reads the information, and then displays a photographic image, onto the most user-friendly of appliances, the family TV. Once a roll of exposed film, or a given number of slides and photos have been processed, there are numerous possibilities. Since the images are digitally stored, the digital prints will give finishers the ability to crop and retouch with great ease. Digital imagining also makes it possible to produce easily various products, such as personalized postcards, business cards via desktop PC.

CD-WORM

In the electronic publishing area, aside from the use of CD-ROM as ideal publishing medium as seen from the proliferation of CD-ROM products (over 4000 titles in the current market place) and desktop CD-ROM publishing, it is now possible for us to not only having ROM products in compact discs, but also write on CDs once with the CD-WORM disc by using the CD WORM technology recently introduced in 1991. For the first time, it is possible for us to write about 600 MBs of infor-mation on a CD which costs around $40 with a system configuration around $10,000.

Clearly, we have entered the digital environment, and have witnessed the fading electronic boun-daries among text, picture, sound, and moving image, and the coming of multimedia information age. In late 1989, a research report on Micro Multimedia predicted that the worldwide market for multimedia products and services will grow from $2.1 billion in 1989 to $15.9 billion in 1994. It was expected that the convergence of end user needs with advances in various multimedia, compu-ter, and communications technologies will drive such growth with $15.9 billion expected to be spent in 1994 in the following areas:

Video games - $4.9 billion

Information retrieval - $3.4 billion

Education/training - $2.6 billion

Professional - $2.4 billion

Other consumer - $2.6 billion.

Although we are only in 1992, yet, all indications seem to suggest that expectation in growth in all areas will be even higher than expected in this prediction. Of these categories, three -- information retrieval, education/training, and professional -- are relevant to the interest of this group!

A few words should be said about information seeking from the users' side. For centuries, we have been conditioned to access information mainly through printed sources. Because non-print information sources could not be readily available to us, we have trained ourselves either not to seek or to offer information available in those formats. Now, with text, picture, sound, and moving image all available in digital form, we clearly see the fading electronic boundaries among them. Once information is being presented in digital format, both the applications developers and users can retrieve the needed information easily, can cut-and-paste as they wish, and can also manipulate it in whatever way they see fit. Taking image as an example, an analog image can only be presented in its entirety as one frame of picture, while a digital image can be stored as a file and retrieved as such as well. Depending on the resolution and scale it is stored in digital format, it presents its users endless possibilities for processing in any way relevant to the users' need, such as zoom in, zoom out, flipping horizontally or vertically, "fat-bit" in looking at each individual pixel, etc...

3. TECHNOLOGY vs CONTENT

In my speaking and publications throughout the years, I have repeatedly stressed that techno-logy is only a tool. It is a very effective means to an end, but not the end itself. What is most significant is the "content." In other words, conceptually how knowledge of a given subject is being structured, and what and how it can be presented to the end-users via the use of the present multimedia technological tools is the most important question.

As we all know, the basic concept of multimedia information access refers to the non-linear and no-sequential ways of accessing information. In other words, an information seeker does not have to follow a specific sequential path to request and/or locate information. Yet, this does not mean that information will be presented in "chaotic" state. In fact, we need to have so much more information organization in order to be able to provide the kind of flexibility so prominently characterized by only "good" multimedia applications. In other words, the developer of a good multimedia information system has to be able to, behind the application, structure so clearly the entire knowledge domain of a chosen topic and provide so many necessary links to those related ideas, concepts, and topics, that the information seekers are permitted to ask for needed information non-sequentially, and without following any pre-determined and pre-structured path.

Even more importantly, good multimedia applications, and the development of multimedia infor-mation systems require a healthy and efficient team work. Most importantly, we need subject/ information specialists to create, select, collect, acquire, and organize all the needed and relevant multimedia information sources; and to decide on how these sources can be utilized, linked, and presented in multimedia applications. In this regards, we talk about quality, value, relevancy, up-to-dateness, comprehensive of information. Without even getting into the subject of "innovation", let's be very specific. Being in Hong Kong in such a free market environment, let's take business infor-mation as an example, it goes without saying that "information" can make or break a company or an industry. In this sense, depending on how it is used, almost any business information -- including manufacturing processes, products, advertising and promotional budgets, competition's finances, market research, legal affairs, field sales, industry forecast, etc... -- may be termed "strategic intelligence." In order to develop a viable shared information system and network to provide this type of information, clearly technology places a supporting role to enable the specialists to gain that very competitive edge in the business environment. Let me stress here the importance of "multi-media" information. Just visualize a strategic analysis session in a boardroom environment, how many presentations can be successful without colorful charts, and illustrations? How much more effective if motions and sounds are also introduced at the right moments?

Having built a rich information resource, we need competent information specialists not only knowing how to organize these information sources with appropriate and advanced methodologies in cataloging and classification, database construction, abstracting and indexing, information retrieval, and information and document delivery; but also utilize these information sources innovatively. This is where technologies come in again! They are tools to help us in every step of the information process, as either already or to be articulated in several of the papers in this conference.

4. MULTIMEDIA AND RECENT DEVELOPMENT IN DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS

Aside from the dynamic growth of computing technologies, it is important to take note seriously of the recent development in communications and networking. "We live in an era of change in modes of communication. Few countries on earth have not already been effected by electronic broadcast technology. Today more and more nations are feeling the increasing effects of modern two-way electronic communication in the forms of cellular telephones and fax machines. Today's emerging communications media differ from those of the past in a singularly important way. Those that had dominated the majority of the 20th century did not inter-operate; telephone, telegraphy and broadcast media stood alone and apart from each other. But, during the 1980's each of these modes went digital, in the wake of computing technology. As a consequence, notwithstanding their perceived differences, voice, music, text, graphics, motion video, numerical data and computer programs have all entered the domain of digital electronics. Today each can be conveyed across a common digital network." By means of digital electronics they can all be created, collected, organized, distributed, reorganized, copied, displayed or performed. Clearly, not only is electronic communication growing faster than communication through the traditional medium of print, but also the convergence of the modes of delivery (print, common carriage, and broadcasting) is bringing newspapers, journals, and books to the threshold of digital electronic communication.... In the past our various modes of communication were separate from each other, and the enterprises built upon them similarly distinct... But today the historically separate modes of communication are converging due to the adroitness of digital electronics.

In this regard, as many of us are still in the midst of developing campus-wide computerized information network, super-developing is going on. Those of you connected to academic as well as industrial research institutions, you are very likely connected to the INTERNET and many other networks. INTERNET is a product of the National Research and Education Network (NREN) in the U.S. NREN is a telecommunications infrastructure that would expand and upgrade the existing interconnected array of mostly scientific research networks in the US. The aim is to reach a 3-GB per second capacity by 1996, increasing current bandwidth by over 2,000 times. To state this capa-city in a simple way, this 3-GB/second network could move 100,000 typed pages or 1,000 satellite photos every second. It will be indeed an information superhighway! The thought of combining this superhighway with the powerful multimedia technologies for information provision to every segment of the society is indeed both mind-boggling and exciting!

Now, digital electronics have prompted the convergence of the historically separate modes of communication. This convergence of the modes of delivery -- print, common carriage, and broad-casting -- is bringing conventional information sources, such as books, magazine, journals, and newspapers; as well as those others -- music, images, motion video, numerical data, and computer programs, to the threshold of digital electronic communication With the advent of digital communi-cation network, multimedia information not only can all be created, collected, organized, reor-ganized, copied, displayed or performed, but also can be distributed and shared globally through high-speed communication networks. Again, since technology is either here or will be ready soon, we should ask again "what are the contents, in multimedia format, which can benefit the end-users through the use of the available digital network? And who is going to create these contents and make them available?"

Time and space limitations do not permit further elaboration on the above discussions. Instead, I choose to end this talk by sharing with you some of the very recent developments of a multi-year cutting-edge multimedia R&D project, PROJECT EMPEROR-I, particularly those since my multi-media presentation at the 2nd Pacific Conference in Singapore in May 1989. While the subject matters of this project may be very different from those of your immediate interests, the multimedia application development is rather generic in nature, and can be applied to almost all subject fields.

5. PROJECT EMPEROR-I'S NEW DEVELOPMENT & APPLICATIONS

5.1. Background

PROJECT EMPEROR-I, supported by the US National Endowment for the Humanities, started in late 1984 as an interactive videodisc project. Since then, because of the technological develop-ment, it has become a rather extensive multimedia application project with more than 60-hour inter-active courseware running on Apple's Macintosh, and also various prototype applications running on a great variety of delivery platforms, such as DEC's MicroVax and IBM PC. It has since been covered in over 15 countries public media, featured on over two dozen international conferences, and a large number (over 70) of professional and general-interest publications.

5.2. Most Recent Project Activities (since 1991)1

Since 1985, the project has grown rapidly, and has a number of major products and activities, which include the production of a set of two 12" NTSC CAV videodiscs, entitled "The First Emperor of China: Qin Shi Huang Di, " in 1985, etc... But, since 1991, efforts have been directed to the continuing of the multi-year efforts in the development of extensive multimedia courseware (more than 60 hours) for both general and scholarly audience, running on Macintosh. In this case, the courseware are used together with the comprehensive set of 4-side videodiscs, The First Emperor of China. Within this multimedia application, system users can access to multimedia information on any related topics -- video segments, images, descriptive information, texts, biblio-graphies, maps, glossaries, commentaries by experts, etc... -- at a simple click of the mouse. In addition, an image database of over 2,000 selected images, with extensive frame-to-frame database and descriptive information, has been built; and capabilities to access selective multi-lingual texts in both English and Chinese have also been provided. These have been developed in the HyperCard environment. Specifically, available commercial and demonstration products include:

A popular version of an one-sided videodisc by The Voyager Company also entitled The First Emperor of China. A popular version of interactive software running on both Macintosh is also avai-lable for distribution from The Voyager Company, and soon the IBM PC version will be available as well; (see Figure 3 for the openning screens of The Voyager's interactive courseware.)

60-hours interactive courses running on Apple's Macs under the HyperCard environments;

Multimedia prototype courses for IBM PCs using Linkway™ and IBM's M-Motion card, as well as for IBM new Ultimedia system using Windows and ToolBook; and prototype multimedia course development on DEC-MicroVax with MIT's Project Athena.

Electronic Image Databases -- Extensive image database of over 2,000 images has been deve-loped on Mac in the HyperCard environment. Joint research activities also took place with several Universities in different parts of the world.

High-resolution image digitization and electronic imaging for high-end applications on Sun Microsystems Sun 3-160, as well as common applications by MicroTek color slide and flatbed scanners. With the cooperation of Kodak, an Initial Test Format Disc of the Kodak's Photo-CD was created.

Converting and creating large textual files with images and Chinese characters by using Micro-Teks MSF-300G image scanner and optical character recognition software. In addition, using Xanatech's Mishu™, we have been successful in finding ways to include mixed English-Chinese languages on the same HyperCard in the word-processing mode.

5.3. Industrial Cooperation and Most Recent Developments and Applications

PROJECT EMPEROR-I has been fortunate to be able to work with a number of leading high-tech companies. These include:

Hardware Software

Apple Apple

Digital Equipment Corporation AimTech Corporation

IBM ASYS Computer System

Mass Microsystems Image Concept, Inc.

MicroTek Lab Image Understanding Systems

Pioneer Kodak

Philip INOVATIC

Sony Xanatech, Inc.

Sun MicroSystems

In addition to the above, the electronic publishing of an interactive multimedia product, a video-disc entitled The First Emperor of China, together with interactive software, involves the cooperation with The Voyager Company. Currently, with Bokförlaget Bra Böcker AB of Sweden, a CD-I pro-duct with full-motion video is being planned.

From the above, it is clear that PROJECT EMPEROR-I has benefited a great deal by the advent of digital technologies. New activities since late 1990 have shifted considerably to the digital domain, although considerable efforts have continued to be made in content building for multimedia course-ware development. The experiment in the digital domain has been related to areas, such as the use of high-end video digitizing boards for full motion video, color image scanning and processing, and the use of Kodak Photo CD Acquire test software, etc...

5.4. The Future

Experience gained in all the above mentioned activities in the digital domain will facilitate PRO-JECT EMPEROR-I's further development in multimedia applications, specifically those using digital information sources. Specifically, in addition to multimedia applications using analog videodisc, developments of consumer-based applications using CD-I with full motion videos is being planned with BBB of Sweden. Educational applications using DVI technologies are being explored serious-ly. Extensive efforts have been made in the last five years in building an extensive knowledge base for the project, the availability of high-quality content materials in multimedia formats will greatly facilitate both the creation of new applications and adaptation to new technological developments.

In the midst of this very dynamic technological environment, PROJECT EMPEROR-I has experienced a wide range of exciting development over time since its beginning. Technology has been indeed utilized as both essential and effective tools in achieving and surpassing a number of rather ambitious goals and objectives of the project. Yet, powerful technology will have no way to demonstrate its potentials without the richness of contents. Our emphasis on the building of the knowledge base and the extensive effort made in conceptualizing and planning for each type of multimedia applications have certainly paid off.

6. CONCLUSION

PROJECT EMPEROR-I is only one of the many examples which demonstrates vividly that technologies are here to assist us in developing very user-friendly and sophisticated knowledge-based information systems. These knowledge bases differ greatly from the conventional type of databases, will revolutionize our information services.

During the 1960s and 1970s, automated information systems were mainly designed to serve staff needs by replacing cumbersome manual systems, filing, and record keeping processes with inven-tory control systems mainly either "borrowed" or derived from the business community. Informa-tion clientele were seldom considered as the primary users of these systems. In the 1980s, service to information clientele became increasingly more important for information systems, and this prompted the development of various online databases and public access catalogs, such as OPAC, in informa-tion centers. As we enter the visual and multimedia information age of the 1990s, it is expected that information systems will have to provide even more dynamic and demanding services to patrons who are increasingly more sophisticated. Thus, printed-based or text-based information systems are no longer satisfactory. The users are becoming more and more demanding for information in all formats -- text, images, and audio -- for information as they think.

For information centers, currently they are in the midst of a period of unprecedented change and adjustment, I have long advocated the need for them to shift focus. In order to meet the complex and diversified information requirements of the industry/academic/research community, modern day information centers must utilize flexible, distributed systems to provide needed information at the workstation level. These systems must be able to support access to multimedia information in a variety of formats as well as materials that are not confined within the four walls of the information centers. Since print-based information provision alone can no longer satisfy the information seekers' needs, multimedia information provision is not only essential but will soon be mandatory. Further-more, in light of the continued exponential growth of information, the increasing demand for infor-mation from a knowledge-based society, and the tremendous financial and space constraints on actual information source acquisitions, the networking of these information systems into national and global information networks is critical. Many of you know that the MIT's Media Lab is known for its provocative role in developing future multimedia systems. At the two-day Celebration Conferen-ce on the Media Laboratory (MIT)'s 5th Anniversary on October 1-2, 1990, at MIT, I remember the titles of a few talks presented by the key speakers

"From the Media's Mind to the Mind's Media: Turning Learning Upside Down," Seymour Papert

"People Will Like Computers More When Computers Act More Like People," Marvin Minsky

"Good-bye to Mass Communication: So Long Broadcast, Newspapers, Books," Nicholas Negroponte

"Television of Tomorrow: Signals with a Sense about Themselves," Andrew Lippman

It should not be difficult for you to guess the contents of these talks even that you were not there. How do these scenarios compare with our current information-related environments? Are our computers acting more like people now? Or, are we telling our system users that they have to con-form to our ways of design, otherwise they won't be able to retrieve relevant information? As an information science educator, I know that many of us have to use a couple of courses to teach retrieval techniques for even just print-based information? We know that we have a very long way to go!

Yet, those systems talked about by some of these futurists are really not future systems. I have been privileged to see some of them, which either are being developed or have been developed, though they may be some distant from perfect.

It is worth mentioning that when Nicholas Negroponte entitled his talk "Good-bye to Mass Com-munication: So Long Broadcast, Newspapers, Books," he did not mean to say that there will be no broadcasts, newspapers, and books. He contended that broadcasts, newspapers, and books will be very different from what they are today. He emphasized that computers will be developed to "know" their users, read for them, and screen the diversified information sources for them. They will also be able to meet their users' information needs automatically from a vast array of sources through the great variety of information delivery systems that we may take for granted in tomorrow's society. He predicts that individuals will increasingly rely upon the use of "filters" to select out the most needed information. Before the end of this century, how many of our information systems will be able to "filter" for our users? Within this context, how is the industrial or academic computing network fit in?

It is undeniable that information technologies have had, and will continue to have a fundamental impact on the manner in which information can and will be used. While it is easy to witness a reali-zation of these new technologies as time progresses, it is important to keep in mind that the whirl-wind pace of new technological developments has generally greatly outpaced our ability and effort to conceptualize..." I realize that as I have run over many current new information technologies which are available to us as tools, I have also raised more questions than answers. These questions are those which we must address in our process to develop innovative information service systems and programs, so that our users can have information for innovation, regardless what field we are in.

We are indeed living in a very interesting time! The challenge is great, so are the promise!

REFERENCES

Chen, Ching-chih. (1987). "Libraries in the information age: Where are the microcomputer and laser optical disc technologies taking us?" Microcomputers for Information Management, 3 (4): 253-265 (December 1986). Reprinted in Proceedings of the First Pacific Conference on New Information Technology, Bangkok, June 16-18, 1987, ed. by Ching-chih Chen & David Raitt. Newton, MA: MicroUse Information. pp. P1-P12.

Chen, Ching-chih. (1989a). HyperSource on Multimedia/HyperMedia Technologies. Chicago, IL: Library and Information Technology Association. pp. 169-178.

Chen, Ching-chih. (1989b). HyperSource on Optical Technologies. Chicago, IL: Library and Information Technology Association.

Chen, Ching-chih. (June 1989). "As we think: Thriving in the HyperWeb environment," in Proceedings of the 2nd Pacific Conference on New Information Technology, Singapore, May 29-31, 1989 edited by Ching-chih Chen & David I. Raitt. W. Newton, MA: MicroUse Information, May 1989. pp. 37-52. Modified version also to be published in Microcomputers for Information Management, 6 (2): 77-98.

Chen, Ching-chih. (1990). "Online hypermedia information delivery," in Proceedings of the 11th National Online Meeting, May 1-3, 1990, New York. Medford, NJ: Learned Information, 1990. pp. 75-79.

Chen, Ching-chih. (December 1991). "The coming of

digital visual information age: Implications for information access," In

Proceedings

of NIT '91: The 4th International Conference on New Information Technology,

Budapest, December 2-4, 1991, ed. by Ching-chih Chen. Newton, MA: MicroUse

Information, 1991. pp. 5-18. Also in Microcomputers for Information

Management, 8 (4): 255-275 (December 1991).