Robert M. Hayes

Graduate School of Library & Information Science

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA

E-Mail:

Abstract: This paper provides a basis for determining the distribution of the workforce among various functions, both internal to organizations using information and within the information industries. It serves as a basis for policy making at both national and corporate levels.

Structure

of Information Industries

Libraries as a Component

THE MODEL

Resulting

Distributions

Percentage Distribution of Workforce

Total

Workforce

USE OF THE MODEL

Librarians

as Components of the Information Economy

National

Policy Planning

General

Economic Policies

Business

planning in General

Business

Plans for "Information Industry" Enterprises

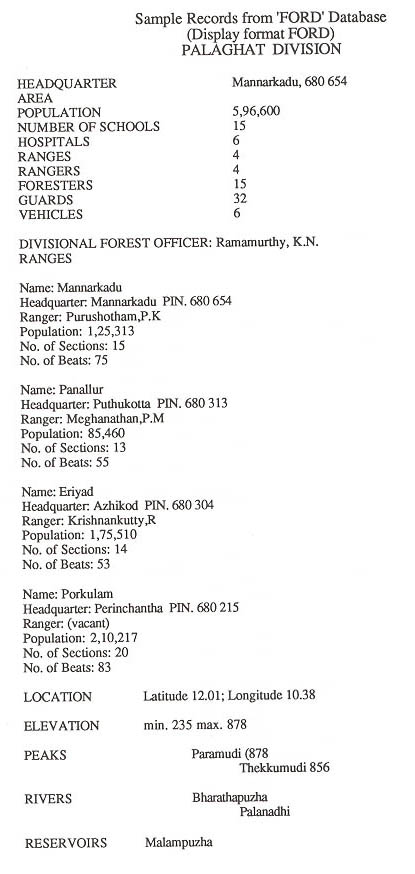

As shown in Figure 1, this paper presents a simplified model for describing the fine structure of national information economies. As background, the introduction briefly summarizes the large-scale structure of information economies. Details of the model are then presented. The model is illustrated with the situation in the United States (including individual states, such as California), and a range of countries in other stages toward development of their information economies. Use of the model is discussed considering issues of importance in national planning, general business planning, and information industry business planning. Special attention is given to libraries and similar organiza-tions.

2. THE CONTEXT

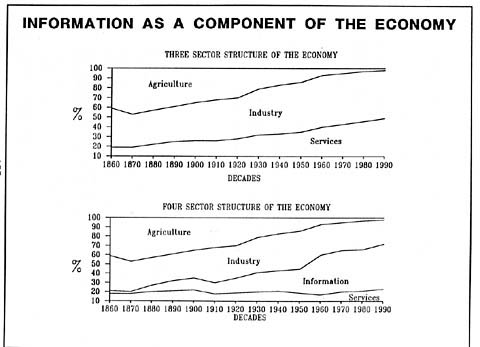

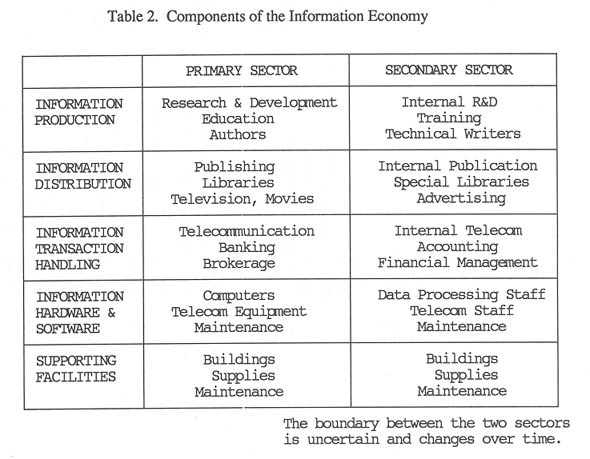

In his landmark study of The Information Economy of the United States, Marc Porat replaced the traditional three sectors of the national economy -- Agriculture, Industry, and Services -- by four sectors, adding an Information sector to them, as shown in Figure 2.

Based on the latter structure, he presented a distribution of the national workforce in three major categories: 1) Primary Information Sector workers, 2) Secondary Information Sector workers, and 3) Non-information workers.

The first, the Primary Information sector, included all persons working

in organizations whose primary product or service was essentially information-oriented.

As Porat illustrated in his The Information Economy, examples of

such organizations and activities include:

• Knowledge Production & Invention• Information Distribution & Communication

• Risk Management (Insurance, in particular)

• Search & Coordination (Brokerage, in particular)

• Information Processing & Transaction Handling

• Computer & Telecommunications Hardware & Software

• A variety of Governmental Activities

• Information Support Facilities

The second, the Secondary Sector, included those persons working

in all other organizations but whose activities were also essentially information-oriented.

In these two sectors, the functions per-formed by information workers are

essentially the same as described in the following:

• INFORMATION PROCESSORS Administrators

& Managers

Process Controllers

Computing Center Staff

• INFORMATION PRODUCERS

Scientists & Engineers

Information Gatherers

Authors

• INFORMATION DISTRIBUTORS Educators

Market Coordinators

Consultants

Librarians

• TRANSACTION HANDLERS

Postal Workers

Communications Workers

Clerical & Accounting Staff

Banking Staff

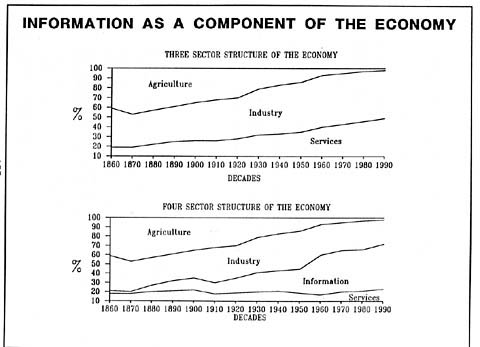

The Porat study has shown that over 50% of the nation's workforce today

is engaged in informa-tion related activities, almost equally divided between

the Primary and Secondary Information sectors, as shown in Table 1.

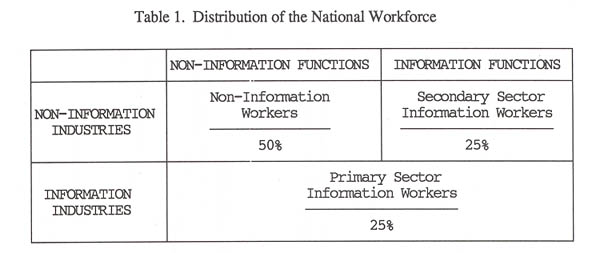

3. STRUCTURE OF INFORMATION INDUSTRIES

Within each sub-sector, information products and services can be roughly, but usefully, classified into five components with obvious parallels across the sub-sectors (Table 2):

• Information Production

• Information Distribution

• Transaction Management

• Information Hardware and Software

• Supporting Facilities and Services

The parallels across the sub-sectors highlight the fact that management has the choice between committing resources to them in-house or contracting for them from the primary information sector. For valid management reasons, though, there does appear to be a steady trend toward drawing on the primary information sector, especially in areas such as software development and training, as illus-trated in the following table comparing, over time, the percentages of various activities that are "out-sourced" (Table 3). To illustrate, industrial training is one of the areas of largest growth in the U.S. economy.

Table 3. Percentage of Services Out Sourced

3.1. Libraries as a Component

Libraries are an identified part of the information economy. But clearly, when we talk of 50% of the nation's workforce, we are dealing with a large-scale phenomenon, based on broad definition of information work, within which libraries and librarians are almost invisible. General studies of manpower distributions have, as a result, not given a clear picture of more specific elements at a level that would permit meaningful examination of libraries as a component of large-scale information economies. It is largely for this reason that the model being presented here was created.

3.2. Row & Column Totals

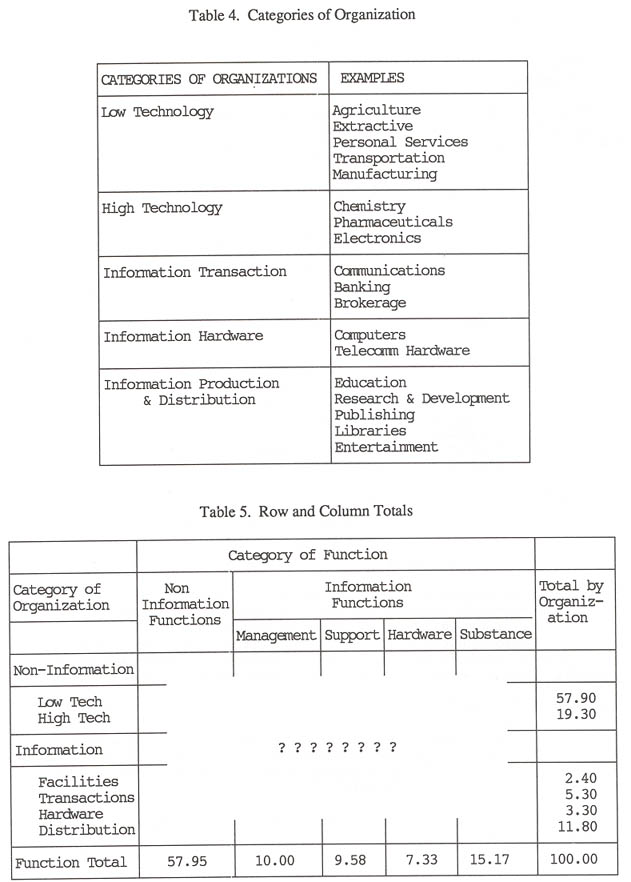

It is relatively easy to obtain data by which to measure the distribution of the workforce by category of organization (from national input/output data) (Table 4) or by category of function (from labor statistics). Those represent the row and column totals, respectively, for the matrix of manpower distribution are shown in both Tables 4 and 5:

The problem of concern in this presentation is the estimation of the

distribution of the labor force within this matrix -- the "fine structure"

of the information economy.

4. THE MODEL

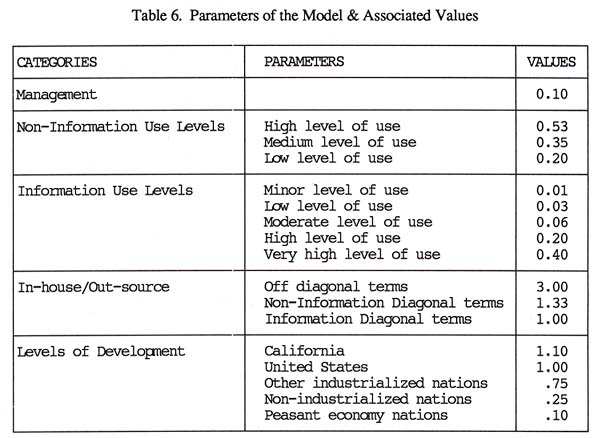

The model presented is intended to be a descriptive basis for assessing that fine structure, not a predictive one, even though it will be presented numerically. So the numbers used to represent the relevant parameters are deliberately at a low level of precision -- just one or two decimal digits. Furthermore, the number of parameters is limited. The following table presents five categories, the parameters associated with each, and values used to represent each. For two categories -- manage-ment and levels of information use -- the parameter is the relevant proportion of total employment in an industry category, as shown in Table 6.

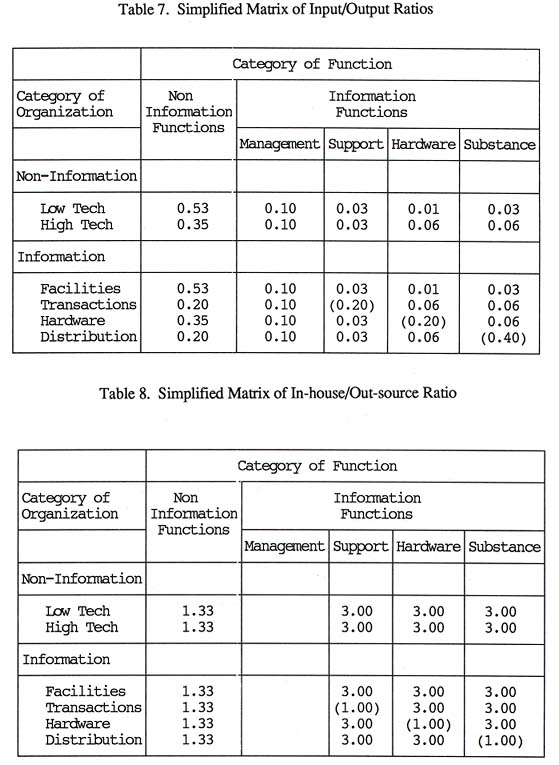

The value for "management" is taken uniformly, over all categories of organization, at 10%, based on the reported data for employment in the United States (Table 7). The values for "levels of use" (information and non-information) are derived from the input/output accounts for the United States and reflect the relative levels for purchase of products and services by different categories of organization.

The values for the ratio "In-house/Out-source" are taken at 3/1 for all functions except those specific to each type of industry. This reflects data, as illustrated above, on that ratio for different specific functions. However, for information industries, there is evidence of a strong "diagonal dominance", with transaction industries purchasing heavily from transaction industries, information hardware purchasing heavily from hardware, and distribution purchasing heavily from distribution. For those diagonal elements, therefore, the ratio is taken at 1/1. For non-information industries, there is a similar diagonal dominance, taken at 1.33/1.

The category "Levels of Development" involves a single parameter, but the table shows five representative values for economies at different stages in transition to "information economies".

4.1. Resulting Distributions

The values for these parameters are distributed as follows in Tables

7 & 8:

In each of these two matrices, the diagonal elements have been emphasized to highlight the difference between them and the other elements

4.2. Percentage Distribution of Workforce

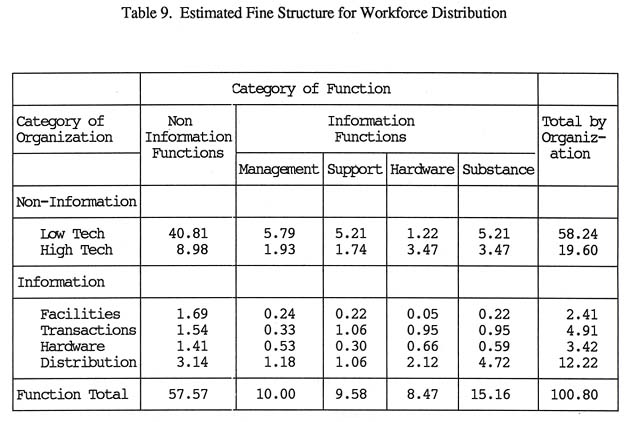

The estimated fine structure for distribution of the workforce is then derived by multiplying the values in corresponding cells of these two matrices with the respective row totals. The result is as follows (Table 9):

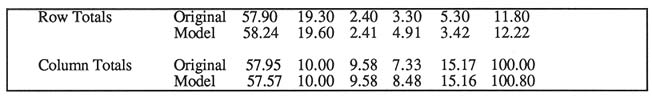

Despite the limited number of parameters and the low precision in the related values, the row and column totals are remarkably close to those from the original data showing in the following:

4.3. Total Workforce

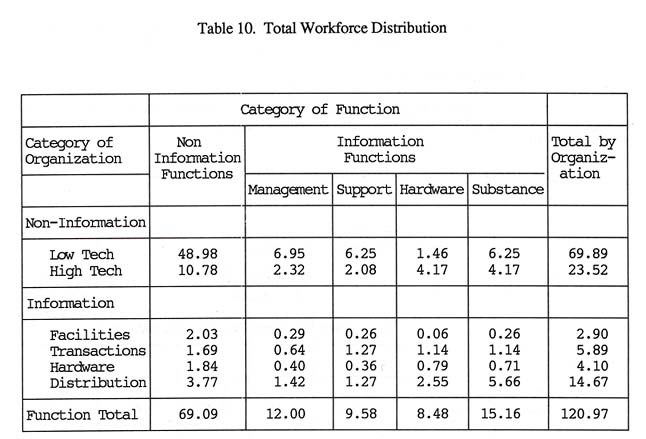

Given the absolute value for the total workforce for the United States (taken at 120 million, for example), the distribution of persons can then easily be derived, as shown in Table 10:

Table 10. Total Workforce Distribution

5. USE OF THE MODEL

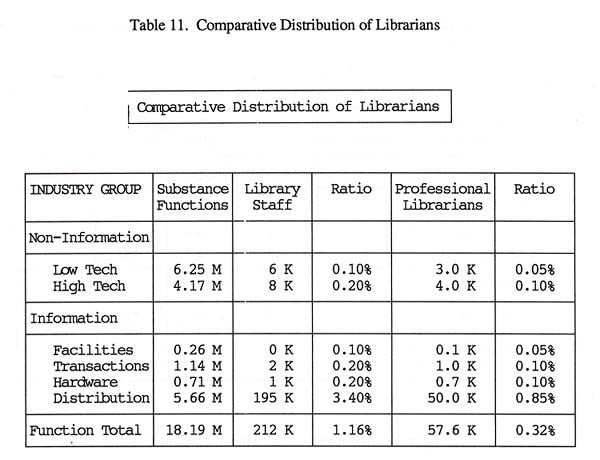

5.1. Librarians as Components of the Information Economy (Table 11)

Librarians are by definition part of the workforce of the "substance" function and, especially, within the "information distribution" industries. In the US in 1989, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, there were about 212,000 of them including both professional and non-professional staff of libraries and library-like agencies. They thus were about 1.3% of the workforce for substan-tive information staffing.

The librarians are heavily concentrated within distribution industries, though, especially in educa-tional institutions. For example, the major university libraries (those that are members of the Asso-ciation of Research Libraries) in 1989 employed about 35,000 persons (25% being professionals); higher education as a whole employed about 90,000. Public libraries employed another 90,000. That leaves about 32,000 for the rest of industry, with about half being professionals.

The distribution of professional librarians (Table 11) among the several classes of industry is derived from statistics for the Special Libraries Association in the US. The important point is the mis-match between those numbers and the workforce engaged in substantive information work in the low technology industries. The implication is that there is a substantial need to upgrade the level of library support in those industries. Most particularly, the amount of use made of "published infor-mation" (the province of the librarian) is dramatically less in those industries than it is in the high technologies.

5.2. National Policy Planning

To this point, the model has been derived as a representation of the information economy of the United States. If that were the end of it, there would be at most descriptive value. The intent in developing the model is to provide a basis for assessment of other contexts, especially those in coun-tries in transition through the stages from subsistence agriculture to industry into the information age.

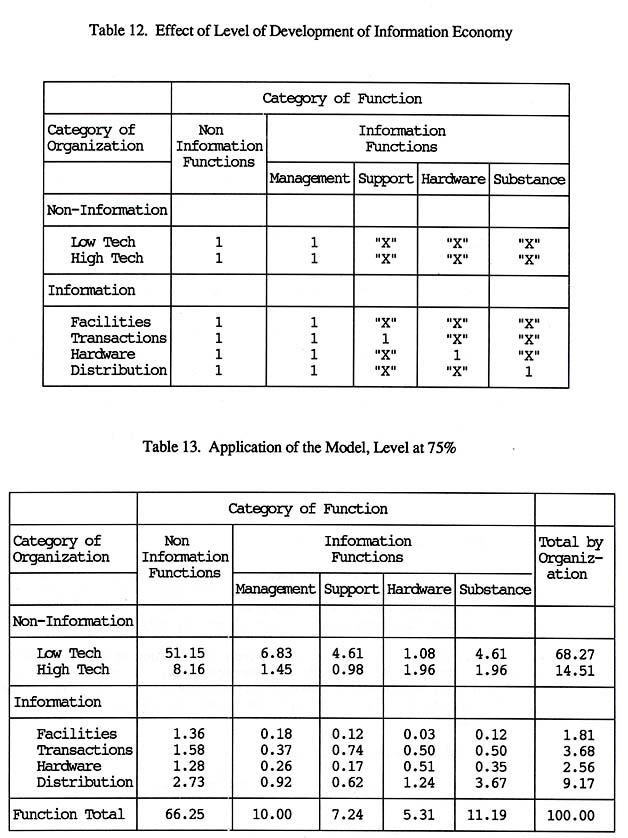

To that end, one more parameter is needed -- one that represents the stage or level in that deve-lopment. The underlying assumption is that the level of development is exhibited in the extent to which various kinds of information resource is used within the economy (Table 12). That parame-ter (shown by "X") enters into the model as a multiplier on the percentage values shown , in the fashion as stated in Table 12.

5.2.1. Illustration with Industrially Developed Countries

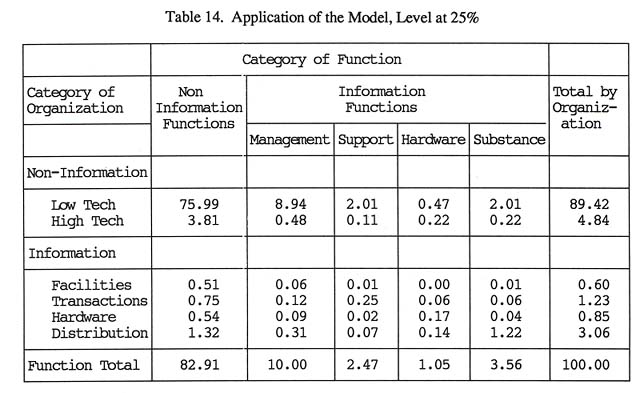

For illustration, the parameter "X" will be taken at .75, representing a typical industrially developed country, as shown in Table 13.

5.2.2. Illustration with Developing Countries

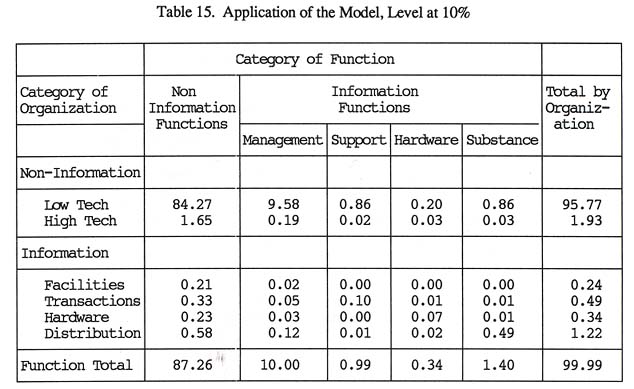

For a second illustration, the parameter "X" will be taken at .25, representing a typical industrially developing country, as shown in Table 14.

5.2.3. Illustration with Subsistence Agriculture Countries

For a third illustration, the parameter "X" will be taken at .10, representing a typical peasant, subsistence agriculture based country, as shown in Table 15.

5.3. General Economic Policies

I will now conclude with a brief commentary on the implications for national policy and Business Planning in an information-based, market-oriented economy. Underlying them is the nature of general economic policies. These implications include a number of politically explosive decisions, a number of sociologically disruptive transitions, and a number of capital intensive requirements as listed in the following:

• General Economic Policies

- Shift from Planned Economy to Market-Driven Economy

- Shift to Entrepreneurship

- Shift from Agriculture to Industry

- Shift from Low Technology to High Technology

- Shift from Production of Physical Goods to Information

• Development of the "Information Economy"

- Encouragement to Effective Use of Information in Business

- Incentives for Development of Information Industries

- Information Skills Development

• Management of Information Enterprises

- Technical Information Skills

- Support Staff

Can these be accommodated and reconciled? While I cannot answer that question, I can say that they are all essential if an information-based, market-oriented economy is to be achieved.

5.4. Encouragement to Use of Information

Assuming that the basic, general economic policy decisions have been made, there are less con-troversial but still crucial elements of national policy. The first is to provide encouragement and incentives for the development of an information economy. A most crucial problem with information is the fact that there is differential use. Those who know the value of information, those who know how to use it are the ones who do so. But all statistics show that they are 10.0% to 20.0% of those who should be using information.

Therefore, national information policy should be concerned with how to encourage managers and staff at all levels to use the information they need for maximally effective operations. That's not easy. There are barriers, both psychological and physical, to the use of information. Managers in fact would frequently prefer not to have information, especially if it may go counter to the decisions they want to make; it is sometimes difficult to obtain the information one needs when one needs it; it is difficult to weigh the validity and import of information when it is provided.

Despite all of these difficulties, however, the values to be gained for the total corporate success are so great that every effort should be spent to ensure that the barriers are removed, that managers are psychologically prepared to use information, and that the information resources are managed in such a way that the full range of needed information is available when it is needed:

• Better work force, better trained and more capable of dealing with problems

• Better product development, based on more knowledge about the needs of the consumer

• Better engineering, based on availability and use of scientific and technical information

• Better marketing, including choices among markets and approaches to them

• Better economic data, leading to improved investment decisions and allocations of resources • Better internal management, based on the use of information and the associated technologies for improved communication and decision-making.

5.5. Incentive for Development of Information Industries

Balancing these aspects, of course, are significant negative factors that can prevent companies from making the necessary internal investments in information resources but that, as a result, provide the opportunities for information entrepreneurs to "fill the gaps." Since there will be great risks for them in doing so, it is essential that there be incentives to reward those risks.

1) Evident costs. Most information activities involve very evident costs, in manpower, in equipment, and in purchases.

2) Uncertain return. And they are also characterized by very uncertain returns. Rarely are the positive results of any of the "benefits" listed above attributable that clearly to the availability of the information on which they were based. In many cases, the decisions could have been made without the information; in some cases, they may even be made counter to the information.

3) Long-term return. And even when the value if evident, it is likely that the return is only over the long-term, while the expenditure is made in the immediate-term. The result is that most informa-tion investment must be amortized over a long period of time.

4) Not directly productive. Furthermore, only in rare situations (and most of those in the "infor-mation industries" themselves) is information directly productive. Its value lies in the better uses of other resources, not in the direct contribution to production. (Although increasing use of computer-based technologies is changing this situation and increasing the direct contribution to production attributable to "information", in the form of programs and data, for most purposes today the role of information is supportive at most.)

5) Overhead expense. As a result, in virtually every accounting practice, information is treated as an "overhead" expense and therefore subject to all of the cost-cutting attitudes associated with overhead expenses.

5.6. Information Skills Development

Throughout this presentation, there has been a continuing theme of needed skills for the infor-mation professional -- the librarian, the information scientist, the information manager -- in effecting this change, in increasing the awareness of information and of its value, is crucial. There must be information professionals with qualification adequate to support management and to justify their investment in information resources. Support to this kind of educational investment clearly should be a priority national commitment.

5.7. Business planning

A Business Plan is created to serve a number of objectives. It provide a statement of the mission for an organization; it serves as the proposal for obtaining capital investment; it provides a blueprint for future development; it can be used as a guide for subsequent planning and management.

A Business Plan traditionally covers the following issues:

• The Company and the Industry

• The Product and Related Services

• The Technology

• The Market and the Market Strategy

• The Competition

• The Means for Production

• The Management and Administration

• The Financial Needs, Risks, and Returns

• The Time Schedule

As I will now discuss in detail, to this traditional organization, I would now add a tenth section -- Information Resource Requirements

5.7.1. Information Requirements as Part of the Business Plan

Turning to the first context -- the development of Business Plans for industries in general -- the primary point I wish to make is that, as we increasingly find ourselves in an information economy, the generic model for a Business Plan needs to be modified so as to highlight the role of information in support of each of its other components. The entrepreneur should be expected to recognize the needs for information in support of the business objectives, and any potential investor should be given clear evidence in the Business Plan of the results of that recognition. To that end, as I have said, I recommend adding the 10th section to the Business Plan:

Information Resource Requirements: This section should discuss information sources that sup-ported development of the Business Plan. It will identify information needs that will arise as part of the development program and of operations, and it will describe how they will be met.

The following discusses some significant elements of the "Information Requirements" Section:

• Information in Development of the Business Plan. What are the sources of information supporting the several sections of the Business Plan, especially with respect to estimates of market, competition, financial needs, time schedule?

Development of a Business Plan depends first upon the vision of the entrepreneur in conception of a product or service and of the potentials in a market that will justify investment. It depends upon the managerial skills of the entrepreneur in organizing a framework within which the objectives in creation of the product and in production marketing and distribution of it can be achieved. But it also depends upon data on which the estimates of costs (for research and development, for manufacture and production, for marketing and distribution) and of income (from sales) can be derived. As I discuss the role of "information requirements" as part of the Business Plan itself, there repeatedly will be the implication of parallel needs for corresponding data to support the process in development of it.

These data include: Industry statistics, product data, state-of-the-art data, market statistics, data on competition, data on vendors and suppliers, specification and standards for needed equipment, data on location and cost of facilities, data on sources of manpower. Among the most important, though, are data on the sources of capital -- the potential recipients of the Business Plan as a proposal.

Beyond the importance to the entrepreneur in development of the Business Plan, there is com-parable, if not greater importance to the potential investor who needs to know that the Business Plan was based on adequate, reliable and confirmable data. It therefore should show the basis for esti-mates; it should show the sources for those data and the means for analysis of them to serve the objectives of the Business Plan; it should relate them to specific sections of the Business Plan.

• Information in Development of the Product/Service. What is the role of R&D, of current state-of-the-art knowledge, of sources for raw materials or components?

If the product/service requirements research and development, the Business Plan should identify the information requirements to support it. It should specify whether the R&D will be done "in-house" or outside and, if the latter, the availability of means for doing it. It should show clear know-ledge of the sources of current state-of-the-art knowledge and of the means for continuing update within the enterprise. It should specify the means for maintaining

• Information in Production. What are the information needs for management of purchasing, for staff training, for maintenance of production quality, for management inventory and distribution?

• Information in Marketing. What will be the means for monitoring penetration of the market, the effects of competition?

• Information in Management. What are the means for providing management information, for measuring the productivity of information support? What are the means for management of the information activities themselves -- the special library, computing facilities, telecommunications, database access services?

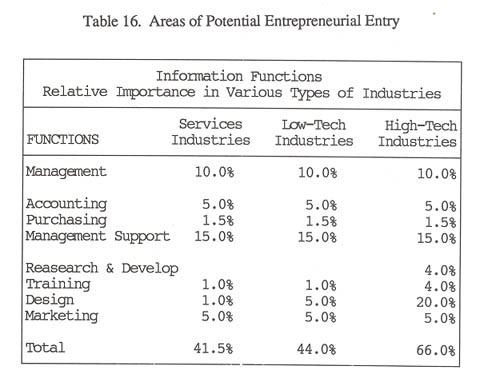

• Representative Parameters for Magnitude of Needed Staffing. To provide a starting point for answering those questions, I will posit some representative parameters for investment and expen-diture in each of these areas, based on data that I have presented previously. To do so, I will distinguish among five categories of industry: 1) non-information services industries, 2) low-technology industries, 3) high technology industries, and 4) information industries.

5.8. Business Plans for "Information Industry" Enterprises

The information requirements discussed above, as part of general Business Plans, can to some extent be met with staff internal to the company -- what we have called the Secondary Information Sector. However, for a wide range of reasons -- access to a wide range of information sources, economies of scale, necessary management skills, investments specific to information activities but irrelevant to company objectives -- there is great value in drawing upon the Primary Information Sector instead. This immediately provides opportunities for information entrepreneurs to fill those needs. They must develop their own Business Plans, following the general pattern outlined above but with special attention to aspects of particular importance to information enterprises. The elements of business planning specific to information industries can be listed as follows:

• Hardware, Software, Facilities

• International Regional Networks

Information Staff Skills

• Corporate Management Skills

• Information Management Skills

• Research, Development, & Design Skills

• Marketing Skills

Information Capital Resources

• Sources of Databases

• Development of Databases

Accounting Practices

• Capitalization of Information Investment

• Overhead Categories

Technical Issues in Accessing Information. If these kinds of resources are to be used effectively, there is need for managerial, technical, and professional skills in the use of them. I won't dwell here on the evident needs for managerial skills; they are those which each of you can recount and evaluate though I think there are special skills needed for management of information-based enter-prises. I do want to outline some of the technical skills, however:

• Managerial

• Technical knowledge of information processes

• Experience with range of information resources

• Operating knowledge of information technology

• Technical knowledge of "systems analysis &design"

First, and in my view most important, is technical knowledge of the nature of information itself -- the processes by which it is generated, organized, stored and retrieved, analyzed, distributed, and used. Here, I must emphasize that I am not talking about the information technologies, but about the information itself. We have only recently, within the past ten to fifteen years perhaps, recognized the necessity of this kind of technical knowledge.

Second, is a solid experience with the full range of information resources that are important to corporate operations, decisions, production. Some of these are the internal information, generated by corporate data processing systems, based on data about corporate operations. These are the primary substance of management information systems. But beyond them are the great variety of external information sources -- the publications, the data bases, the governmental statistics, the scientific and technical information sources. The information resource manager needs to know what kinds of information are available, but even more important is the knowledge of how to identify those that are needed for specific requirements, as they arise.

Third, is operating knowledge of the information processing technologies. These are the means by which information processes are carried out, and the information resource manager needs to have solid understanding of them. Central among them are the technical tools of database management -- indexing structures and vocabularies, file structures, software for search and retrieval of data from files, tools for data analysis and presentation.

Fourth, is a technical knowledge of "systems analysis"--the means by which technical decisions can be made about the choices among alternatives that will meet the objectives of the corporation. I must emphasize that this is far more than the traditional "systems and procedures" that have become such standard parts of corporate data processing operations. While the issues of concern in systems and procedures are clearly important and indeed are included in the work of systems analysis, there are much larger problems and more sophisticated methods involved in "information systems analysis and design" than simply systems and procedures in the traditional sense.

6. CONCLUSION

The objective in presenting this model was to provide a simple structure within which to experi-ment with the effects of alternative strategies in the development of national economies. Among the most crucial requirements is an adequate workforce of "information professionals", among which librarians have been used as an illustrative example. The model permits one easily to assess areas which lack adequate staff and to formulate policies for filling the needs.

The model also provides a basis on which business entrepreneurs, as well as public policy makers, can assess the areas of business opportunities as the information economy develops. It permits identification of growth and decline as the economy and size of the population change.

As presented, the model is deliberately simplified, with a limited number

of parameters deli-berately presented at a low level of precision. The

values generated match the actual data closely enough to warrant use as

a tool for identification of areas in which greater accuracy and reliability

are needed.

BIBLIOGRAPH

Bearman, Toni Carbo; Guynup, Polly & Milevski, Sandra N. (1985). "Information and produc-tivity," Journal of the American Society for Information Scienc, 36 (6): 369-375.

Bell, Daniel. (1979). "The Social framework of the information society," In The Commuter Age: A Twenty-Year Review. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp. 163-211.

Borko, Harold. (1983). "Information and knowledge worker productivity," Information Process-ing & Management, 19 (4): 203-212.

Hayes, Robert M., ed. (1985). Libraries and the Information Economy of California: A Con-ference Sponsored by the California State Library. Los Angeles: GSLIS/UCLA.

Hayes, Robert M. & Erickson, Timothy. (December 1982). "Added value as a function of pur-chases of information services," The Information Society, 1 (4): 307-338.

Horton, Forest Woody, Jr. (1982). "Rethinking the role of Information," Government Computer News, 2 (4): 2, 24.

Kantor, Paul. "Three studies of the economics of academic libraries," Advances in Library Admi-nistration and Organization, 5: 221-286.

King, Donald et al. 1983. Key Papers in the Economics of Information. White Plains: Knowledge Industry Publications.

Porat, Marc Uri. (May 1977). The Information Economy: Definition and Measurement. Washing-ton, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Telecommunications.

Rubin, Michael. (1983). The Information Economy. Denver, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Siegel, Donald & Griliches, Zvi. (April 1991). Purchased Services, Outsourcing, Computers, and Productivity in Manufacturing. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

US. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science. (February

1, 1982). Public Sector/Private Sector Interaction in Providing Information

Services. Washington, DC: National Commission on Libraries and Information

Science.