Salvacion M. Arlante and Rodolfo Y. Tarlit

University of the Philippines Library

Abstract: One of the reasons for the relatively slow take-up

of microcomputers in libraries in the Philippines is the problem caused

by the multitude of languages used in the island group. The paper examines

the dimensions of the problem, focusing on local scripts, lexicon, semantics

and orthography, and provides some solutions. It is concluded that there

is an urgent need for continuous design and experimentation on the applications

of microcomputers in handling the various language problems of the Philippines.

As far as Philippine libraries are concerned, the microcomputer is a relatively new technology that is currently used as librarians' partner in processing, storage and retrieval of information for their various clientele. While the microcomputer is now a standard tool in libraries in the West and some rich Eastern countries, this is far from true in the Philippines. Only a few of the many academic and research libraries in the country own a microcomputer solely for library use. Its power and utility as it is known in the West have not been put to its maximum use.

At this early stage of microcomputer application in Philippine libraries, librarians have already met some problems. More specifically, these problems concern storage and retrieval of library materials that are written in the vernaculars or what are known as Philippine languages. This paper focuses on these problems and what we have done or thought should be done to solve them.

2. THE PHILIPPINES AND HER LANGUAGES

The name "Philippines" by which the country is known today, was given in 1543 by the Spanish navigator, Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, in honor of Prince Philip of Asturias, who later became King Philip II of Spain.

The Philippines is one of the largest island groups in the world, with around 7,200 fragmented islands and rocks above water. It is situated on the Eastern rim of the Asiatic Mediterranean, the warm and shallow waters between the Pacific and Indian Oceans and between Australia and the Asian Mainland. This position finds the Philippines at the crossroads of international travel lanes.

The so-called "Philippine languages" are as numerous and varied as its fragmented islands and the ethnic groups which inhabit them. They are the various vernaculars spoken in the Philippine archipelago. They are called "languages" rather than "dialects" because they are mutually unintelligible. Estimates of their number vary from 86 to 150.

These languages belong to the great Austronesian family of languages, which extends from Formosa in the north to New Zealand in the south, from the island of Madagascar off the African coast, to the Easter Islands in Mid-Pacific. The total number of languages in this family is estimated to be around 500, i.e., about one-eighth of the world's languages. The Philippine languages are sometimes referred to as "Malayo-Polynesian" because they belong more immediately to the Malayo-Polynesian sub-group, branch of the Austronesian family of languages. To this Malayo-Polynesian sub-group belong the languages of Indonesia, Malaysia, Madagascar, Formosa and the Philippines.

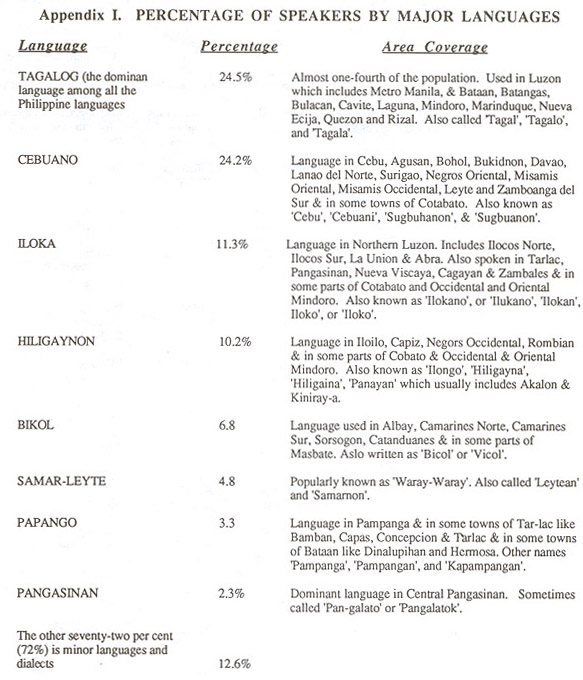

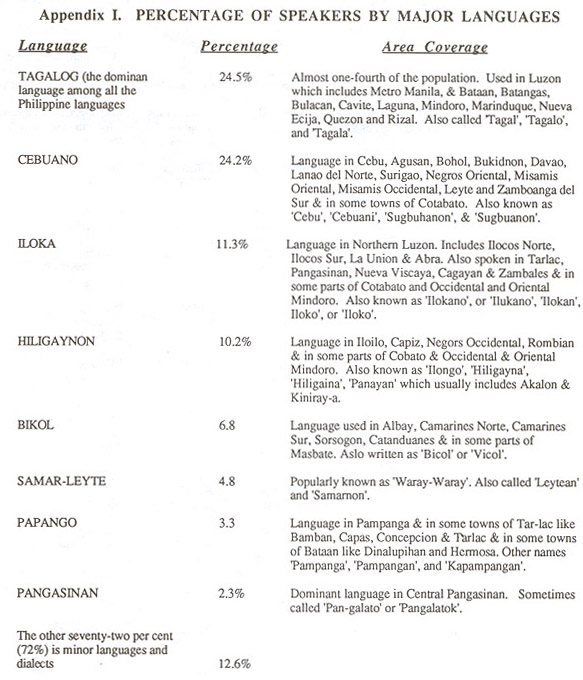

There are eight "major languages" of the Philippines, namely Tagalog, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray (or Samar-Leyte), Ilocano, Pangasinan, Pampango and Bicol (see Appendix I). The other Philippine languages could not be included in the category for major languages because normally a major language either: a) has about one million speakers; or b) assumes importance in the country because of its role as medium of instruction, official or national language. The other languages that do not belong to the major languages do not have the requisite number of speakers nor are they used for the special purposes mentioned above. There are about 70 to 90 "minor languages" in the Philippines, which are divided into: a) Minor Christian Groups; b) Muslim Groups; c) Non-Christian and Non-Muslim Groups; and d) Negrito, Dumagat and Mamanwa.

There are three official languages in the country today -- English, Spanish and Filipino. By "official language" is meant a language which has a legal standing in the courts, government transactions, education, commerce and industry. Until recently, Pilipino, a Tagalog-based national language was one of three official languages until it was replaced by Filipino as per the new Philippine Constitution and the President's Executive Order.

Roughly, this is the language picture in this country today. Although these languages are in some ways grammatically and lexically similar, they also have enough differences so that they are mutually unintelligible.

The present linguistic situation in the Philippines creates a dilemma for the Filipinos themselves. On the other hand, the imperatives of nationalism make it an urgent task for Filipino society to develop its national language, Filipino (finally selected by the framers of the 1987 Philippine Constitution) not only as a language of everyday life anywhere in the country, but likewise as a language of education and scholarly discourse.

Language is not simply vocabulary nor dictionary. Language involves culture. And culture encompasses language. For the culture of any group is only expressed in its language. Language means more than aspirating certain sound forms. As a whole, the national language that seems to be emerging is a lingua franca - a native tongue overlaid with borrowed influences. Talk of cognates or identical meanings, yes, the country linguistically speaking can share many, many words. But language is not lexicon. Pilipino is cognate with these major language families only 36.16 percent which means that within our linguistic area, we have lexicon where 63.8 percent happens to be an area of confused meaning. The area of misunderstanding one another is therefore greater than the area of understanding one another.

Each of the major languages has several dialects that differ especially at the phonological and lexical levels. This language situation in the Philippines presents several problems with respect to microcomputer applications in libraries, information and documentation centers.

3. VERNACULAR LITERATURE IN PHILIPPINE LIBRARIES

In Philippine libraries, the existing collections include among others local or vernacular materials which have a rich array of rare manuscripts and literary writings in different Philippine languages consisting of holographs, typescripts, published monographs and periodicals, and original manuscripts which are of interest to local as well as foreign researchers. In the University of the Philippines Diliman libraries, special collections in Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilokano, Hiligaynon, Pampango, Pangasinan, Waray, Mangyan scripts, are numerous and varied.

The collection development in the regional cultures and vernacular languages of the country does not end with the mere gathering of materials. The organization of these collections, including the preparation of research guides, indexes, bibliographies, catalogs and other finding tools or retrieval aids becomes an overwhelming task for librarians. Retrieval of such materials is equally tedious if not a more difficult task. Today, we expect that the emergence and application of the microcomputer facility would lessen or even solve our problems. As far as we know, this has not been so!

4. THE MICROCOMPUTER IN PHILIPPINE LIBRARIES

Mainframe computers were introduced in the Philippines in the early sixties with applications in processing research data; organizing census and statistics and other government data; managing financial accounts; and inventory and storage of personnel records.

Then, only libraries whose parent organizations owned mainframe computers could design and experiment computer applications in library and information work. Libraries in the Philippines and perhaps in most developing countries with computer centers in their organizations, have been slow or had little progress in using computers for various reasons, namely:

• Library professionals lack the knowledge to design and develop computer programs with library applications;

• Low priority given to library operations, especially automation by managers;

• Prohibitive cost of hardware, product and services, and computer supplies; and

• Lack of knowledge and application by users of computer technology.

Today, new and exciting possibilities for library automation have opened up with the development and availability of microcomputers with powerful memories and large storage capacity, faster response time, and most importantly, as far as poor and developing countries are concerned, at affordable costs.

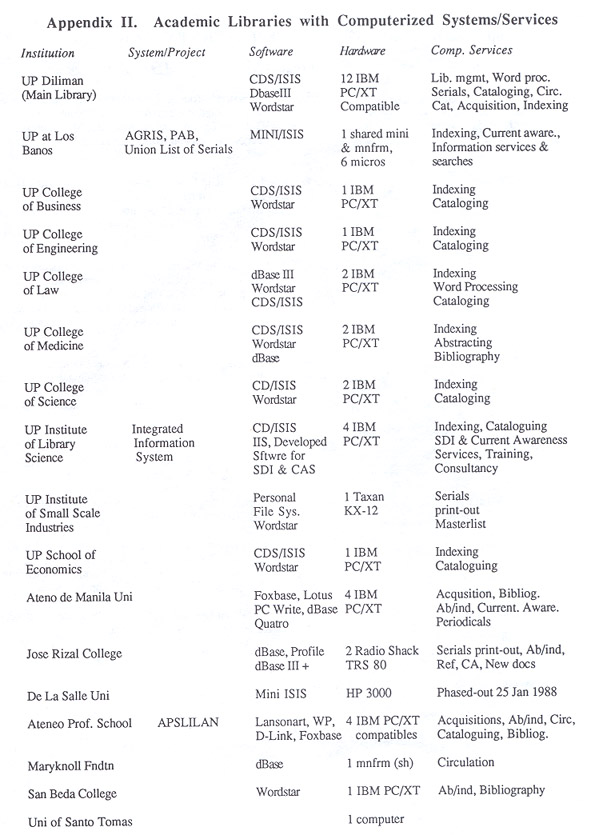

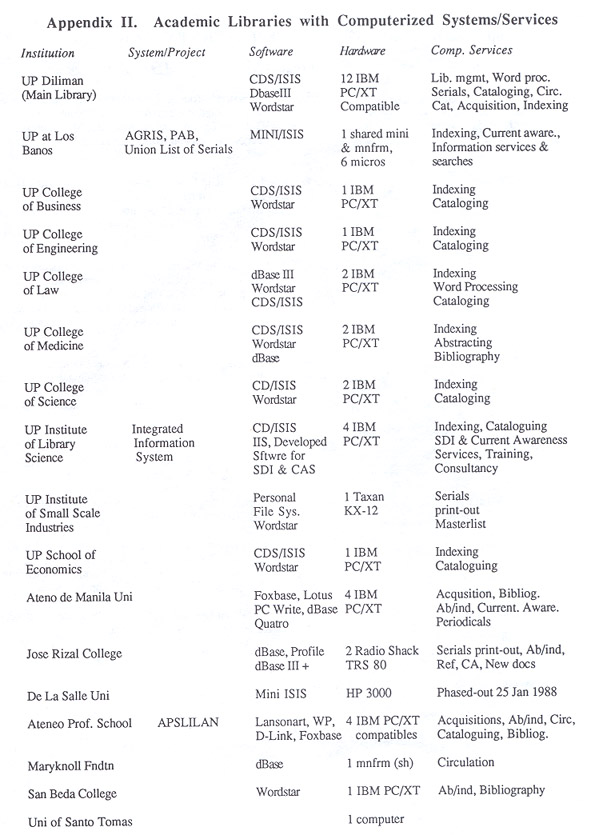

In relatively rich countries, the microcomputer is now almost a universal utility in offices, libraries, including homes and schools. However, there is a different situation pertaining to the Philippines. A survey of 123 academic and research libraries in the Philippines of which 98 responded, conducted in 1986 by the U.P. Main Library and updated recently (October 1988), showed that only seventeen libraries offerer computerized services (see listing in Appendix II) in the areas of administration such as budget control, statistics, personnel records, word processing, reports, minutes, memoranda and correspondence; technical services such as acquisitions, cataloguing; and public services such as circulation back-up, computer-assisted reference and query systems, preparing and updating guides to literature, selective dissemination of information (SDI) profiles and current awareness service (CAS).

During the survey period, we had an occasion to talk with librarians regarding their problems encountered in the application of microcomputers. Not a few talked about language problems. We are now presenting to you these experiences and problems with the hope that these would be considered by the more experienced and rich countries in the production of application software and hardware in the near future.

5. PROBLEMS AND SOLUTIONS

5.1. Local Scripts

It is a well-known fact among Asian paleographers that there exists a writing system in the pre-Spanish Philippines. The Negritos, the aboriginal inhabitants of the Philippines, did not have a writing system of their own but the later waves of moving peoples or migrants who came to the Philippine Islands, used characters of their own. Established reports give enough evidence that this script is related to Indian scripts that found their way through the Indonesian archipelago. This later wave of migrants wrote and made notes of their activities on thick joints of green bamboo, palm leaves, banana leaves, using a knife, steel points and other sharp instruments.

Scripts of the Philippines that are still being used today are found among some primitive tribesmen on the islands of Mindoro (the Hanunoo Mangyans) and Palawan (the Tagbanuas) in Central Philippines. The Hanunoo Mangyan scripts are syllabaries in nature. Each character stands for a syllable, that is, either a vowel, or a consonant with open end-vowel. In the basic character, this end vowel is always "-a." The number of characters in the Mangyan scripts is greatly limited compared to the large number of signs employed in expressing the Sanskrit language, or even Javanese or Balinese. This limitation in number is due to the simple phonetic structure of the Mangyan languages that belong to the Philippineasian branch of the great Austronesian linguistic family. This limited number of characters in the Hanunoo Mangyan scripts may puzzle anyone because certain phonemes cannot be adequately expressed by the available characters. For example, the language that employs the Northern Mangyan script possesses the fricative "F" consonant in its phonetic structure, but it is instead expressed in writing by the character for "PA". The Southern Mangyan script on the other hand, knows the alveolar flap "R" consonant but when written, the character for "LA" is used. These often give rise to misunderstandings. The Northern Mangyan script has a separate character for "R".

Another difficulty is the fact that the Mangyan scripts are read depending on who wrote them. They are read from left to right when the writer is right-handed. When the person is left-handed, he will write the characters in the mirror-face fashion, and the script has to be read from right to left.

Materials of these type are available in the University of the Philippines Library and perhaps some other big academic libraries in the Philippines. These have not been transcribed nor catalogued. Hence, they have not been brought to the attention of researchers.

The U.P. Diliman Library has recently created bibliographic databases (index, book and theses databases) and such materials in local scripts could not be encoded in our computers for the simple reason that the micros available do not have the facility to handle them. Other countries such as China, Korea, Japan, Thailand, India and Sri Lanka have successfully produced microcomputers to deal with character-type languages. The Philippines, on the other hand, is way behind in this area. We have not even ventured into producing microcomputers much more developing one that could handle these local scripts.

Microcomputer producers should therefore take notice of such developments in the above-mentioned countries. It is certainly a tall order but it is most desirable to develop an all-purpose hardware that will take care of all possible characters that are used in almost, if not all character-type languages in the world, including of course the Philippines.

5.2. Lexicon

Philippine lexicography is a problem. The system of affixation of Tagalog is so complicated that it is never easy to determine which derived words to include and which ones to exclude when compiling a dictionary. There is no single standardized dictionary or normative grammar and/or vocabulary for all terms in the Philippine languages. A reliable dictionary is a 'must' for speakers of Philippine languages that are very much simpler in morphology such as many of the languages in the southern parts of the country. Culturally significant items outside the Tagalog regions for which there are no Tagalog words are not adequately covered in the existing dictionaries. A dictionary of the national language should also reflect native culture on a nationwide basis. When a single standardized dictionary shall have been compiled or developed, then it could be made as a guide or authority list for librarians, information specialists or documentalists in the processing and retrieval of vernacular materials through the computers. It can be made as an authority in indexing and assigning descriptors which have nonequivalents in existing English subject authority lists. This dictionary must also incorporate all diacritical marks, accents and/or stresses and the meanings of a term in all Philippine languages. The same dictionary may be used as a reference when searching the various databases which include among others vernacular literatures.

With reference to microcomputers relating to this task of compiling an all-purpose dictionary, we pose these questions: What is the possibility of using microcomputers to develop or produce such dictionary and/or vocabulary? To what degree are microcomputer applications successful to about 86 to 150 languages? Perhaps, these are possible. However, it is such a gigantic task and gathering all terms of the 150 languages will probably take us a lifetime to accomplish.

5.3. Semantics

The language problem is also a problem of semantics. "Wala" in Pangasinan means "mayroon" (there is/are - in English). In Tagalog, "wala" means nothing or empty. Now watch the following:

"Pating" in Tagalog is a "shark". In Hiligaynon, it means "pigeon" or "dove". Pigeon or dove is a kind of bird. In Tagalog, bird means "ibon". But bird in Cebuano means "langgam". Now "langgam" in Tagalog means "ant". But ant or ants in Cebuano means "humilgans". And "pating" (shark to the Tagalogs and pigeon to the Ilonoggos) is "iho" in Cebuano. This sounds like "hijo" (son) in Spanish. And the fun can really begin. Much too many words in these languages have the same spellings and sounds but connote different meanings. A concept in one tongue would simply turn out to be the opposite in another tongue. There is, therefore, a need to reconcile opposite and discrete concepts. Is the microcomputer capable of reconciling these opposite and discrete concepts? How would it affect storage and retrieval of information via the computer?

We can foresee a possible solution to such a problem. This may be done by assigning a code to indicate variations for every meaning of one term representing the different Philippine languages for purposes of storage and retrieval.

In the U.P. Diliman Main Library, we are presently studying the possibility of assigning codes to indicate variations in meanings of terms that are present in the different Philippine languages and that are encoded in our databases. We hope that with the use of codes, each meaning of a term that has the same sound and spelling in the different languages will be stored and retrieved separately by the microcomputer. Hence, if one wishes to search "pating" to mean pigeon or dove, all he does is key in the term plus the code for the language, e.g., "pating + code". He may also search for its English equivalent or equivalents in other languages for a relevant and 100 percent retrieval or hit from the databases.

5.4. Orthography

The problems in orthography are relatively simple but a knowledge of Philippine phonetics show that there are troublesome ones. One serious problem that besets the Filipinos with regard to orthography is how to treat borrowed words. The problem does not surface in the oral or spoken phase of the language. The moment, however, when what one says orally is written down, the problem suddenly presents itself. The graphic presentation cannot show references to things understood, facial expressions, noises, and the entire motion of the body. Words do not make a language. A dictionary is not a language, nor is a vocabulary. One can purse his lips and transmit a message or idea. The language is not a mere matter of orthography, not the listing of new words. While it is true that the microcomputer can handle the written word, will it be able to represent the true meaning of the sound corresponding to its written form? We surmise that diacritical marks, accents or stresses may be used to represent the different sounds for words with the same spellings but different meanings. If encoded in their natural written form, the difference cannot be distinguished. For example: take the word "Mama". In its natural written form, "Mama" may either mean "mother" or "man". Its meaning may only be distinguished when it is pronounced or when marked with appropriate diacritical or stress symbols. If one says, Mamá, he means mother; if he says Mamà, he means man.

An examination of the ASCII (American Standard for Information Interchange) shows that there are 123 extended reference codes for the IBM computers that may serve to indicate diacritical marks, stresses or accents for almost, if not all words in Philippine languages. We can not immediately determine if such extended reference codes may be used to represent all sounds found in world languages. There is, therefore, a need to compare the symbols of the International Phonetic Association (IPA) and the ASCII. If the latter is found wanting, the production of microcomputers that will represent all IPA sounds is in order.

5.5. Costly and Varied Hardware

Many of the libraries in the Philippines still put library automation low on their lists of equipment and capital priorities. They tend to assume that someone else will meet this need-- through special state appropriations, foundation grants, or gifts from yet unidentified private donor. What they should be doing is to give top priority to such needs both in their requests and in allocations. Administrators of organizations, institutions and agencies consider the library as non-priority and regard microcomputers as very costly.

It is not only the prohibitive cost of computers and computer peripherals such as printers and storage devices that act as a deterrent to the use of microcomputers in libraries for the language problem but also variations of hardware. Although the development of hardware is continuous, attempts to standardize them among manufacturers have not been made. As a result, one machine does not accept the software on another.

6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Philippine libraries hold a collection of materials in the various vernaculars or Philippine languages. The use of microcomputers has facilitated to some extent the storage and retrieval of these materials. We say to some extent because there are a number of problems which librarians have met in using the microcomputer to handle processing of these materials.

In this paper, the problems presented concern storage and retrieval of: a) local scripts, b) terms with the same sound and spelling but with different meanings, and c) terms with the same spelling but pronounced differently. Also presented is the lack of a normative grammar or vocabulary and/or standardized dictionary to be used as an authority for assigning index terms or descriptors. The prohibitive cost of microcomputers and its peripherals and low priority given by administrators to libraries were also dealt with.

Corresponding solutions to these problems have also been offered in this paper which suggest the urgent need for a continuous design and experimentation on the application of the microcomputer in handling the varied language problems of the Philippines in the midst of rapid technological developments.

REFERENCES

Association of Southeast Asian Institutions of Higher Learning. Language problems in Southeast Asian Universities: Seminar papers & discussions. Bangkok: ASAIHL, 1968.

Blake, Frank R., "The study of Philippine languages at John Hopkins University and its bearing on linguistics science," Reprinted from the Johns Hopkins Alumni Magazine 14 (4): (March 1926).

Del Rosario, Gonsalo. The Pilipino language: a potent tool for knowledge, [s.l: s.n.]

Frei, Ernest John Tagalog as the Philippine national language: Thesis (Ph.D.). Kennedy School of Missions, Hartford Seminary Foundation, 1947.

Gallego, Manual V. The language problem of the Filipinos: speech delivered in the House of Representatives (Sept. 7 & 8, 1933) Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1932.

Linguistics across continents: Studies in honor of Richard S. Pittman. Summer Institute of Linguistics (Phils), Manila, 1981.

Gonsalez, Andrew and Bautista, Ma. Lourdes S. Language surveys in the Philippines, (1966-1984). Manila: De la Salle University Press, 1986.

Handbook for teaching Pilipino speaking students. California: California State Department of Education, 1986.

Jacob, Ave. & Perez, Pilipino, "A language in need of genuine writers," Clippings from the Philippines Free Press, January 12, 1963, together with other articles on Philippino from various sources, Manila, 1963.

McFarland, Curtis D., Comp. A Linguistic atlas of the Philippines.

Institute for the Study of Languages and Culture of Asia and Africa, Tokyo

University of Foreign Studies,1980.

Metzler, Douglas P., et. al., "An Expert system approach to natural language processing," Proceedings of the 48th ASIS Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, Nevada, October 20-24, 1985, edited by Carol A. Parkhurst, Published for the American Society of Information Science by Knowledge Industry Publications, Inc. New York, c1985.

Oracion, Timoteo S., "Some notes on the problems of the national language in the Philippines," Foundation University Graduate Research Journal 4 (1): 1-18 (September 1987).

Perez, Alejandrino Q. and Santiago, Alfonso O. Language policy and language development of Asian countries. Pambansang Samahan sa Linggwistikang Pilipino, Ink. Manila, 1972.

The Propaganda of the Filipino language: anq pagpapalaganap nq wikanq Pilipino. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1944.

Studies in Philippine Linguistics 5(2), Linguistic Society of the Philippines, Manila, 1979.

Studies in Philippine Linguistics 6(2), Linguistic Society of the Philippines, Manila, 1986.

UNESCO-UPILS Asian Regional Seminar/Workshop on the application of microcomputers to library and information management, Diliman, Q.C., 29 October 2, November 1984, Proceedings.

Yap, Fe Aldave. A comparative study of Philippine lexicons. Department of Education and Culture, Institute of National Language. Manila. 1977.

Wang, Teh-Ming. Common origin of all languages... an outline... Summer Institute of Linguistics, Manila, 1961.

Zorc, R. & David, Paul. The Bisayan dialects of the Philippines:

subgroupings and reconstruction . Thesis, Cornell University, 1975.