Hong-too Lim

Nanyang Technological Institute Library

Singapore 2263

Keywords: Library automation, Library co-operation, Library networks, MALMARC, SILAS, SingaporeAbstract: This paper traces the introduction and development of library automation in Singapore, beginning in the early 1970s. It divides the development into three phases, and analyses and discusses each phase in the light of interlibrary co-operation and the creation of a national bibliographic database for Singapore. The first phase (early 1970s to 1980) is considered a phase of inactivity, with only attempts at promotion and experimenting with the use of the computer for library operations. However, it was during this period when a conference was held calling for the setting-up of a national bibliographic database. The second phase (1980-86) was brought about by Government encouragement and was marked with unprecedented activities in creating and implementing automated systems for routine library operations by the major libraries. Taken as a whole, this period was marked by activities which are not coordinated. Instead of interlibrary cooperation in matters relating to automation, there was rather sharp interlibrary rivalry. The third phase (1986 - ) started with the creation of SILAS (Singapore Integrated Library Automation Service). The advent of SILAS makes the creation of a national bibliographic database possible.

1. INTRODUCTION

In terms of introducing and using library automation, the library profession in Singapore may be described as largely conservative, resistant to change and lacking innovative spirit before 1980, despite a small group of activists from the rank and file, attempting to promote and experiment with the use of computers for library operations.

On August 17, 1980, the Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, in his speech at a National Day rally, urged the people to prepare for changes that come with the age of the computers. This speech marks the watershed between inactivities and lack of interest and achievements of the period before 1980 and the tremendous enthusiasm and activities after 1980. However, the achievements of the post-1980 period were brought about in isolation. Not only was there no interlibrary co-operation in automation, there was, in fact, a very high degree of interlibrary rivalry. Judging from the variety of systems being installed, it is clear that the idea of a national bibliographic database was not in anyone's mind, or at least it was not the priority. The priority was to achieve distinction or glory for one's own library. Later, the polytechnic libraries started to adopt turnkey systems for use, and the Nanyang Technological Institute Library joined MALMARC as a subscribing member. These are MARC-based systems, paving the way for future interlibrary cooperation in automation.

The setting-up of SILAS (Singapore Integrated Library Automation Service) in 1986 marks the second watershed in the sense that it is a vehicle for bringing about cooperation amongst the libraries with the hope of creating a national bibliographic database. The introduction and implementation of library automation in Singapore may, therefore, be taken as being in three phases, separated by the two watersheds, mentioned above:

(1). The first phase, from early 1970s to 1980, followed by the first watershed, the Prime Minister's speech, 1980

(2). The second phase, from 1980 to 1986, followed by the second watershed, the creation of SILAS, 1986

(3). The third phase, 1986 onwards.

2. THE FIRST PHASE (Early 1970s to 1980)

This is the phase of inactivity. There was no official support, and hence no funding for either hardware or software for library purposes. Moreover, the cost of hardware was exorbitant, being at a time before the advent of microcomputers; and whatever software necessary had to be developed in-house. The leadership in the library profession was not at all convinced of the importance of automation. Whatever expertise was acquired in this period was entirely due to the initiative and interest of the individual librarian. However, there was a small group from the rank and file of the library profession playing an active role in promoting library automation by writing in the official journal of the Library Association, by running courses, and by holding a conference. It is interesting to note that the Conference held in 1978, the Joint PPM Conference on Information Infrastructure for the 80s, passed these resolutions:

• to urge libraries to work towards the establishment of a national database,

• to recommend to heads of major and other interested libraries to set up a working committee to work towards co-operation in automation,

• to consider the adoption of a MARC-based database model.

These resolutions, however, were completely ignored by almost all the major libraries.

3. THE SECOND PHASE (1980 - 1986)

Following the Prime Minister's speech on August 17, 1980, this period was marked by unprecedented activities. These activities were aimed at meeting only the needs of the individual libraries themselves.

Some examples are:

• National Library created a SINGMARC database to provide a union catalogue on COMfiche for itself and its branches, with plans to extend the union catalogue facilities to other Government departmental libraries, but nothing similar was offered to the other libraries in Singapore. SINGMARC was, therefore, never intended as a cataloguing standard for the whole nation to follow. When SILAS was set up later, with LC MARC as the standard. SINGMARC was scrapped and the National Library had to convert all its records in SINGMARC format to LC MARC format.

• The National University of Singapore Library adopted the MINISIS software for the functions of acquisitions, cataloguing periodical indexing, and information retrieval. MINISIS is an excellent system for indexing and information retrieval, but it is not MARC compatible. Hence, it is not much good for interlibrary co-operation. The NUS Library also developed an automated circulation system and a serials control system in-house.

• The Ngee Ann Polytechnic Library developed an online circulation system in-house in 1983 and adopted a fully integrated online real time system, the URICA system, in 1985. The NP Library converted its card catalogue into the URICA MARC-based catalogue.

• The Singapore Polytechnic Library installed a Virginia Tech Library System (VTLS) in 1984. The SP Library also converted its card catalogue into the VTLS MARC-based automated system.

• The Nanyang Technological Institute Library set up a MARC-based cataloguing system by joining MALMARC as a subscribing member. Being a new Library set-up in 1981, the NTI Library introduced library automation in its operations right from the start.

This period was characterized by sharp interlibrary rivalry. It is interesting to note that almost all the major libraries were keen to publicize their efforts at automation and to claim to be first in the implementation of their system. Interlibrary rivalry has its good as well as bad effects. It is good if it results in healthy competition spurring libraries concerned to strive for greater heights. It is bad because it invariably results in libraries alienating themselves from each other regarding matters of automation, whereby losing the opportunity to consult each other. Without such consultation most librarians would be vulnerable to unscrupulous computer vendors due to their inexperience in handling the new technology. This may result in costly mistakes.

4. THE THIRD PHASE (1986 - )

This phase started in 1986 with the creation of SILAS, and we are now still very much in it. SILAS runs a shared cataloguing service for Singapore libraries on a national basis. It started off with the National Library as member in the first phase of its development in 1986. In April 1987, the SILAS network went "live" and incorporated all the major libraries in its second phase. At the end of its third phase in late 1988, SILAS had 35 libraries cataloguing online against a database of some five million records in the MARC format. The SILAS database includes the WLN (Western Library Network) database, the entire LC MARC records, UK MARC as from 1980, selections from the Dutch National Database (PICA), the entire Bibliographic Information on Southeast Asia (BISA), as well as holdings of the participating libraries in Singapore. It is being updated by the addition of the latest releases of LC and UK MARC records.

4.1. Conversion of Catalogue Data to MARC Format

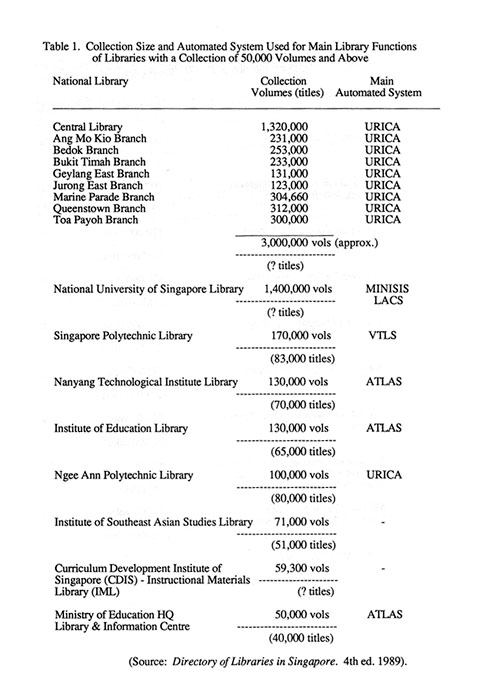

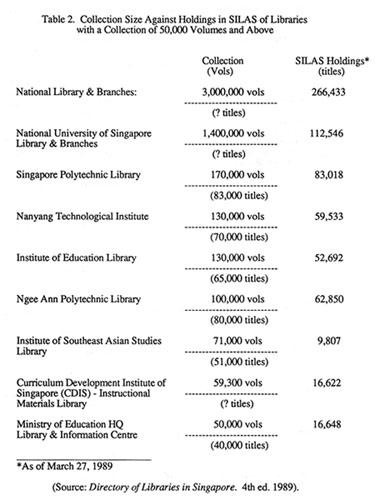

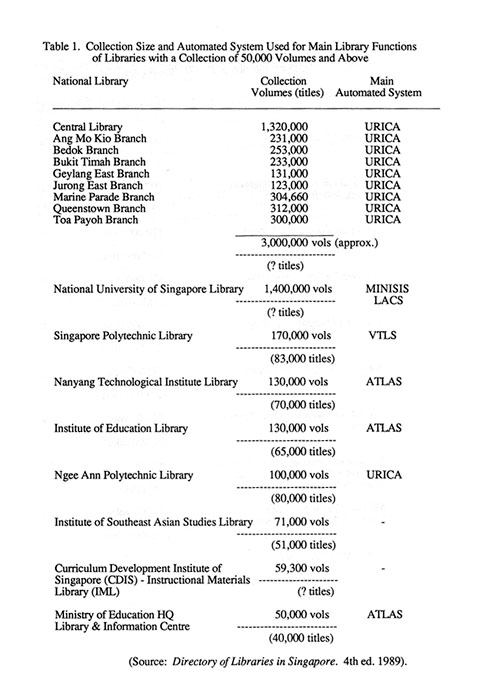

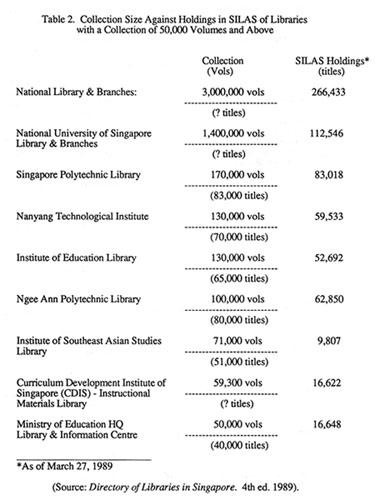

With SILAS, there is a good chance for all libraries in Singapore to convert their catalogue data to the MARC format. Table 1 shows collection size and the automated system adopted for the main library functions of libraries with a collection of 50,000 volumes and above. Table 2 shows collection size against holdings in SILAS, indicating the amount of conversion yet to be done. A close look at Table 2 will reveal the fact that the following libraries have already, or almost, completed their conversion:

• Singapore Polytechnic

• Library Nanyang Technological Institute Library

• Institute of Education Library

• Ngee Ann Polytechnic Library

The National Library and the National University of Singapore Library still seem to have a great deal of conversion to do. Their holdings, in terms of titles, are difficult to ascertain.

4.2. Towards a National Union Bibliographic Database

The union catalogue, or union bibliographic database, being held by SILAS has more than half a million records, or 570,261 unique titles, as of March 27, 1989. There would be substantially more if all libraries have completed their conversion. How useful a union bibliographic database is may be demonstrated by the use of a SILAS terminal for a search. One would have access to the holdings of all the participating libraries all at once. This is instant information for any serious student or research worker. How good a national union bibliographic database it is going to be in the future would depend on how complete the conversion is going to be.

4.3. Cooperation

The activities of SILAS have brought librarians from different libraries together in cooperative cataloguing projects. One example is the cooperative cataloguing of Southeast Asian Materials. Libraries participating in this Project are the National Library, the National University of Singapore Library, the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Library, the Institute of Education Library and the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) Regional Language Centre (RELC) Library.

4.4. Turnkey Systems

The trend at the moment is towards adopting the use of turnkey systems as local systems for functions other than cataloguing in conjunction with the use of SILAS terminal s for shared cataloguing. As shown in Table 1, turnkey systems such as URICA, VTLS and ATLAS are being used by institutions shown in the following:

URICA National Library & Branches

Ngee Ann Polytechnic Library

VTLS Singapore Polytechnic Library

ATLAS Nanyang Technological Institute Library

Institute of Education Library

Ministry of Education HQ Library & Information Centre

References

1. Directory of Libraries in Singapore 4th ed. Editors, Foo Kok Pheow, Lim Hong Too, Singapore, Library Association of Singapore, 1989.

2. Information Infrastructures for the 80s, proceedings of a Joint LAS-PPM Conference held at the Regional Language Centre, Singapore, 7 - 9 December 1978, (Edited by Michael Cheng) Singapore, Library Association of Singapore, 1980.

3. Lim Hong Too, The development of automated library systems in Singapore, Singapore Libraries, 14: 9 - 12 (1984).

4. Lim Hong Too, The extent of library automation

development in Singapore: A background paper, In The New Information professionals:

proceedings of the Singapore-Malaysia Congress of Librarians and Information

Scientists, Singapore, (September 4-6, 1986), Edited by Ajita Thuraisingham

& Aldershot, Gower 293-296, 353-361 (1987).