EXTENDED LIBRARY SERVICES: Online

Instruction & Online Access from the University's Residence Halls

to the University Library: A

Critique and Evaluation

SERVICOS BIBLIOTECARIOS EXTENDIDOS:

Instrución y

Acceso en Línea Desde

las Residencias Universitarias hasta

la Biblioteca Académica:

Crítica y Evaluación

Renee N. Anderson and Wendy A. Culotta

University Library and Learning Resources

California State University

Long Beach, CA 90840, USA

Abstract: Between Fall 1988 and Summer 1990, at California State University, Long Beach, California, two thousand students had the opportunity to learn to use the li-brary's online computer and two commercial online database services from the dorms. Instruction and access to these services were provided at no charge through computers and terminals in the suites of two librarians who were participating in the CSULB Faculty-in-Residence program at CSULB. In the Faculty-in-Residence program, the librarians provided their services during ten hours a week of office hours and by appointment. The online catalog (CLSI, then NOTIS) and databases through BRS and DIALOG were taught to interested students. The students who used this service increased in numbers as the word-of-mouth spread.

The online instruction from the dorms was unique for several reasons. It was from a remote location other than the traditional location in the library. It allowed for one-to-one instruction during flexible hours and with flexible time for the instruction. The instruction yielded a tangible product, the printout which could be matched against the library's holdings - in that session. And it allowed the librarian to work with a body of students who knew her. We will discuss the online services from the dormitories in the context of the Faculty-in-Residence program, the promotion of the online service, handouts, problems, sample searches, feedback, costs, and the future of this service.

Resumen: Entre septiembre de 1988 hasta Agosto de 1990, mas de 2000 estudiantes en la Universidad del Estado de California en Long Beach (CSULB) tuvieron la oportu-nida de aprender a usar 1) dos servicios de información electronica y 2) el sistema elec-tronico de la universidad. Instrución y acceso a estos servicios fueron proveidos a ningun costo por medio se computadoras y terminales en los suites de dos bibliotecarias que estaban participando en un programa de Facultad en Residencia en los dormitorios de CSULB. En el programa de Facultad en Residencia, las bibliotecarias ofrecieron clases durante las diez horas de la semana dedicada a este proposito y tambien por cita. Los sistemas electronicos que se usaron fueron BRS y Dialog. Tambien se enseno el uso the NOTIS el sistema electronico de la biblioteca que da accesso a todos los materiales en la biblioteca. Los estudiantes usando este programa instrucional incre-mento mucho cuando noticia del programa se promulgo en los dormitorios.

La instrución electronica de los dormitorios fue unica. La instrución y acceso era de un local remoto, no la tradicional biblioteca. Esto permitio instrución individual y flexi-ble. Las horas de instrución daba resultatos concretos a los estudiantes: una lista de referencias specificas en la materia deseada que se podia comparar con las materiales accesibles en la bibliotecas. Todo esto se pudo completar en una session con la compu-tadora y la ayuda de la bibliotecaria profesora.

The Faculty In Residence Program at CSULB is unique. A search of the literature yielded several references addressing resident hall libraries [2,5] and faculty involvement with students in the dormitories [1,3,4,6]. None of the articles, however, related the teaching of online searching by resident librarians in the dorms.

The CSULB program started in 1985 with the building of Parkside Commons. Each of the nine new resident halls in Parkside has a suite of apartments for one Faculty In Residence who lives in the halls for one to two years. Librarians, faculty at CSULB, were part of this program in 1987/1988, 1988/1989, and 1989/1990, offering classes and instruction in online searching of the library's catalog and commercial databases. Each librarian had a computer, terminal, modem, and telephone line installed in their suite. We will summarize the activities in the 1989/1990 academic year.

2. PROMOTION OF THE INSTRUCTION

Promotion for this innovative extended library service was widespread. The Coordinator for the Faculty In Residence program distributed fliers to each resident which listed the Faculty In Residence, their specializations, office hours, and phone numbers. The faculty themselves posted this flier and other fliers which they created on the doors of their suites. Fliers were also sent for posting to the student Resident Assistants in each of the dorms in Parkside Commons and the neighboring Residence Commons. The central office for Parkside and Residence commons also posted fliers on their bulletin boards. Often, too, faculty posted fliers on the exit doors of the cafe-teria when midterms and finals drew near.

Librarians also took part in "programs with punch" i.e., a series of timely classes addressing pertinent topics such as "Taking Finals", "Managing Stress", and "Time Management", sponsored by the Office of Housing. This series was printed on bookmarks and distributed to all residents. The highlighted weekly program was displayed on a poster in the offices by the mailboxes of each of the commons.

Each semester the faculty held open houses for the residents. Demonstrations of the compu-ter services were available at these well-attended events.

The best promotion was word of mouth. When one student came, the next to appear were the roommates and the suitemates of the original student.Then students who knew people in that wing of the building came. Then other friends in the building, and finally students from other buildings and the other residence halls came to a class to learn online searching.

3. EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES

Classes were conducted with limited equipment and supplies. An IBM computer, a terminal, an external modem, a phone line, and tractor-feed paper were supplied either by the library or through grants from CSULB's Faculty Loan Program. Librarians also had copies of the online manuals for the evening and weekend services.

The support for the classes mainly consisted of guides to the library's collections and ser-vices which had been prepared for classes in the library by CSULB librarians. Among these instructional tools were the Online Database Searching Workbook [8] and the following fliers: Downloading Your Online Search, Search Strategy Worksheet, Serials Record, and the Student Information Guide. The Librarian also had Interlibrary Loan Request forms.

4. SYSTEMS ACCESSED

Instruction in the use of the library's online catalog (CLSI, then NOTIS, called COAST by CSULB) as well as evening and weekend commercial online services from BRS, DIALOG, and STN were offered. Librarians used the instructional databases prepared by BRS and DIALOG for training potential future users of their respective evening and weekend databases services. DIA- LOG's instructional database for Knowledge Index is Classmate. BRS's instructional database for BRS After Dark is BRS Instructor.

For help in locating materials the librarians also had access to ORION (UCLA's online cata-log), MELVYL (the UC system's catalog), and OCLC. These systems were used only for locating sources retrieved in the online search. Instruction in their use was not a part of these classes.

5. THE INSTRUCTION

Since many of the students were unfamiliar with the library and its G services, the librarian introduced the session by explaining that the instruction from the dorms was part of a larger end-user online service which had been available in the library for a modest fee of $3.00 for each fifteen minutes since the early 1980s. She explained that subject librarians were available in the library to talk to if the student wished more in-depth assistance and consultation in their subject areas.

The librarian explained that the online instruction that they were going to receive was an introduction to the full library service. It would prepare them for future research papers by making them familiar with a fast and economical service. And familiarity with the commands and search techniques would save them money later on.

The instruction had an informal pattern. The student told the librarian what he needed. The librarian helped him write down the search question so it was stated in a sentence. The librarian then queried the student about his familiarity with online services, databases, and computers in general. With this information the instruction could proceed, tailored to that student's knowledge and background.

Students in general were unfamiliar with the concept of online vendors and with the methods by which the vendors supplied their services. With diagrams the librarian explained the route the search took, from the dorms to either New York or northern California, and back to the dorms.

Search preparation, the commands for searching, and search strategy were covered next. The databases, then the vendors, were selected.

The student sat down at the computer and logged on. To orient the student, the librarian briefly explained what the telecommunications software, SMARTCOM, and its macros did. When the system was connected, the student performed his own search, with the librarian coaching and counseling from the chair beside him. In this way the student could confidently practice logging on, choosing databases, entering commands, executing strategies, and reviewing and revising his search. In some cases both the student and the librarian had to put their heads together to expand a search to a sufficient number of pertinent references, and to find productive databases. In other cases, both had to work to refine the search so it produced a reduced number of citations. Cross database searching was encouraged.

The online search session continued until the librarian and the student were satisfied that sufficient results had been retrieved for the student to complete the work he needed to do.

In over half of the classes, the student also chose to spend time logging on and searching the library's online catalog, COAST (NOTIS), completing the work necessary for the identification of his journal and monographic citations in the library. Where the library did not hold a reference, the librarian recommended the Interlibrary Loan service to the student and provided him with the forms to prepare.

6. SAMPLE QUESTIONS

Students were in two main groups: the upper division students preparing papers for their classes and the lower division students, taking general education courses and seeking references for speeches, debates, or papers. The question and the level of the of the student's research, in addition to the number of references found in any database, prompted the decision to search other databases until both the student and the librarian were satisfied with the results.

Upper division students needed information, for example, for five to ten page papers on:

Knee or lower leg injuries to soldiers

What class of people plays golf

urban development and post colonialism

Behavior problems in the classroom

TDD and TDYs and hearing dogs

Warm up exercises for cricket

Recreation projects for children with cancer

Criticism on Paul's Case

Tissue (skin) repair

Lower division students, for example, needed information on

Foot fetishes

Teen-age pregnancy

coaches betting on their own team

Swimming activities for children

Marketing ethics

Recent articles on Mandela

Political platforms

Premarital counseling

Students were again advised that in-depth subject

librarian help was available in the main library if they wished to pursue

the topic with a specialist.

7. DATABASE USE AND TIME ONLINE

The number of users by month is summarized in Table 1:

Table 1. 1989/1990

_________________________________________________

Sept Oct Nov Dec Feb Mar Apr May

8 4 8 1 5 9 17 11

_________________________________________________

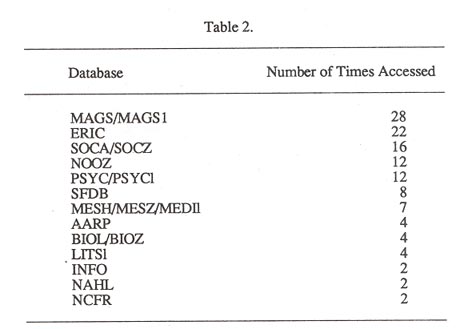

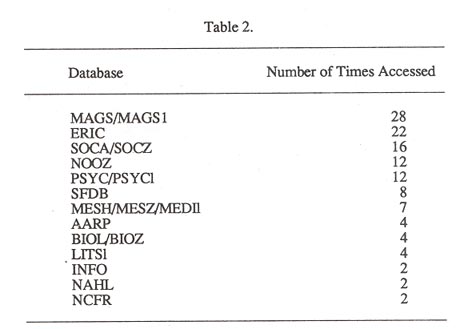

In addition to the online catalog, COAST (NOTIS), twenty-two databases from both the BRS Instructor and Classmate instructional databases were accessed at least once. In order of the number of uses these databases were:

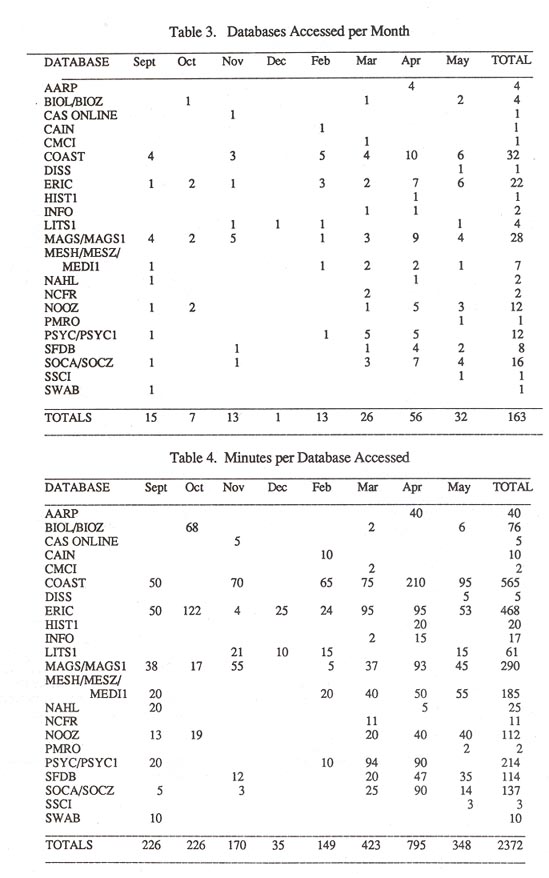

The following databases were accessed once: CAIN, CAS ONLINE, CMCI, DISS, HIST1, PMRO, SSCI, SWAB. The twenty-two unique databases were accessed one hundred sixty three times. Most databases were in BRS Instructor which was the vendor of choice of the instructor in 1989/1990. Monthly data is summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. Table 3 lists the databases accessed per month.

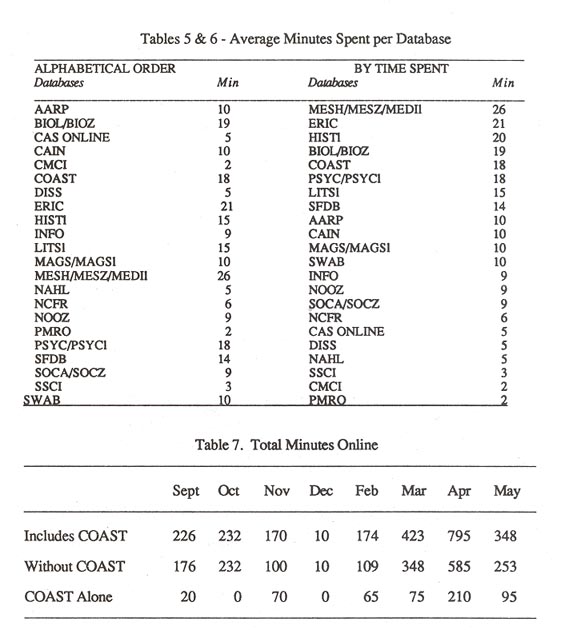

Table 4 documents the minutes online per month. Tables 5 and 6 list the average minutes online in each database. Table 7 summarizes the total minutes spent online per month.

8. COSTS

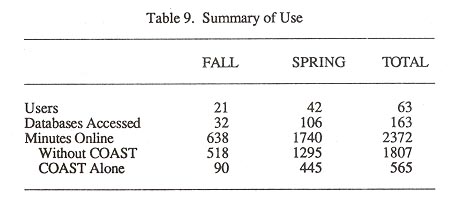

In all, 2372 minutes were spent accessing databases in the online classes. Deleting the time spent searching COAST (565 minutes), a total of 1807 minutes were spent online in the commercial databases.

Both BRS's and DIALOG's instructional databases cost $15.00 per hour. This cost includes telecommunication charges and citation costs. (Though the CAS Online pricing structure is different with the 10% discount for academic libraries, the authors feel the average cost is approximately the same as for the other two services being considered. So for this part of the

analysis, the CAS Online charges for the five minutes used were averaged in with the costs of other services.)

The 1807 minutes is 30.12 hours. At $15.00 per hour

for 30.12 hours, the total online costs were $451.75. Sixty-three students

used the service in 1989/1990. The cost for training the student to search

BRS After Dark or Knowledge Index in 1989/1990 from the residence halls

was $7.17 per student.

9. ANALYSIS OF THE SERVICE AND SUMMARY

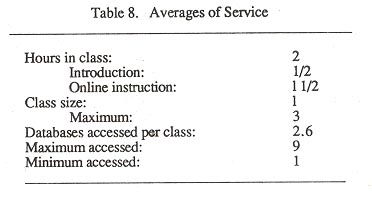

Table 8 summarizes the averages of the service.

Increase in the use of the service between Fall and Spring semester was dramatic. Table 9 summarizes the usage. The number of students in the classes doubled in the Spring semester from twenty-one to forty-two students. The number of times databases were accessed trebled. Online time more than trebled. The total minutes online almost tripled. Curiously, if the minutes on COAST are removed, the total number of minutes online only went up two and one-half times - a little more than the number of users. But minutes on COAST increased almost five times - way out of proportion to the doubled number of users.

In addition to the use of the databases, the residents had the advantage of one-to-one instruction in the use of online database searching. There was no time limit for the instruction or the practice so the student could question, experiment, and search under ideal conditions: no pressure and ample counseling.

The hours for the availability of the instructional databases allowed the student to receive training at any time it was convenient to him, whether at the posted class hours or by appointment.

One disadvantage of the service was the lack of support materials such as the thesauri for ERIC and MEDLINE. Without these basic tools, the searcher had to spend time online identifying the thesaurus terms in pertinent references retrieved, and modifying the search to reflect them.

Ideally document delivery would have put a finishing polish to this very service oriented program. But as a pilot project, both authors are satisfied with their online instruction success through the CSULB Faculty In Residence program.

10. CONCLUSION

Most of the students utilizing this instructional opportunity had no knowledge of the database services but had familiarity with computers. Many had used the online catalog COAST with less than satisfactory results. These sessions helped both classes of online students. Those reporting back with successful grades or speeches documented the success and value of this method of service and instruction.

Through this extended library program the library

demonstrated an innovative service and was able to reach a remote campus

location and an isolated population. The Faculty In Residence program facilitated

the instruction of the library's new technology to students when they were

ready to learn to use it. The one-to-one instruction provided a natural

pace for the student to learn and left much time for questions and experimentation.

REFERENCES

1. Colwell, Bruce W., "Faculty Involvement in Residential Life," Journal of College and University Housing, 13: 9-14 (1983).

2. Keleher, Jean, Deborah Tenofsky, & Robert Waldman, "The Residence Hall Libraries at the University of Michigan," Colleges & Research Libraries News, 51: 222-225 (1990).

3. Kuh, George D. et al., "Suggestions for Encouraging Faculty Student Interaction in a Residen-

ce Hall," NASPA Journal, 22: 29-37 (1985).

4. Miller, Donald E., "Live-in Faculty: A Modest Proposal for Higher Education," Futurist 17: 61-63 (1983).

5. Oltmanns, Gail & John H. Schuh, "Purposes and Uses of Residence Hall Libraries," College & Research Libraries, 46: 72-177 (1985).

6 Schuh John H & George D. Kuh, "Faculty Interaction with Students in Residence Halls," Journal of College Student Personnel 25: 519-528 (1984).

7. Witucke, Virginia, "Off-Campus Library Services: Leading the Way," College & Research Libraries News, 51: 252-255 (1990).

8. Littlejohn Alice C. & Joan M. Parker. Online

Database Searching Workbook.. Long Beach, CA: California State University,

Long Beach, 1988.