Retos para el Bibliotecario y

Profesionales de la

Información en una Era

de Información Visual

Ching-chih Chen

Graduate School of Library & Information Science

Simmons College

Boston, MA 02115, USA

Abstract: In the last decade, there have been tremendous technological changes in every area of information technology -- the advent of personal computers, worldwide packet networks, optical discs and other mass storage media, interactive video techno-logy, image technology, computer graphic technology, multimedia/hypermedia techno-logies, and the growth, both in size and number, of massive public and private data-bases -- bibliographic first, then numeric, and now multimedia.

In this dynamic technological environment, information seekers are no longer satis-fied with only print-based information. Fortunately, advances in multimedia techno-logies make it possible now for us to provide instant information access to all types of information -- text, data, still image, motion picture, and sound. In order to do so, undoubtedly many different pieces of technologies are required to support such type of integration. This paper will discuss what hypermedia is in today's dynamic information environment and the effect of new technological developments on hypermedia applica-tions in recent months. Real examples of a few hypermedia applications, specifically those of PROJECT EMPEROR-I, will be offered. The challenges and opportunities for librarians and information professionals will be discussed.

*This is an expanded and modified version of two keynote speeches delivered at the International Symposium on the Future of Scientific, Technological and Industrial Information Services, Leningrad, USSR, May 28-31, 1990; and the 45th FID Conference, Havana, Cuba, September 18-21, 1990.

En este dinámico ambiente tecnológico, los usuarios no

quedan satisfechos con infor-mación impresa únicamente. Afortunadamente,

avances en el area de la tecnología de multimedios hacen posible

la provisión instantánea de todo tipo de información

-- tex-tual, datos, imágenes, pelicula y sonido. Muchos tipos de

tecnologías son necesarias para lograr tal integración. Esta

ponencia discute el rol de los hipermedios en el diná-mico mundo

de la información, además de presentar el efecto de los nuevos

adelantos, ocurridos en los ultimos meses, en la aplicación de hipermedios.

Serán presentados varios ejemplos, tomados del Proyecto Emperador

I. Se discuten los retos y las oportunidades que ofrece esta tecnología

para los bibliotecarios y profesionales de la información.

In every area of information technology -- computing, communications, and content -- there has been tremendous development over the last decade. In the area of computing, we have watch-ed: the advent of personal computers, worldwide packet networks, optical disc and other mass storage media technologies, interactive video technology, image technology, computer graphic technology, scanning technology, voice technology, animation technology, and multimedia/ hypermedia technologies. In the area of content, we have witnessed the growth both in size and in number of massive public and private databases -- bibliographic first, then numeric, and now multimedia. In the area of communications, there has been enormous development in electronic digital communications via which multimedia information can be transmitted worldwide at an incredible speed. Computing, communications, and content were rather disparate in earlier years, but are becoming increasingly integrated and quite international in scope and impact. In addition, we have also seen the convergence of all these new information technologies with conventional media.

Information seekers are no longer satisfied with

only print-based information. Advances in multimedia technologies make

it possible now for us to provide instant information access to any type

of information one desires -- text, data, still image, motion picture,

and sound. Thus, as we enter into this "Visual Information Age," the challenges

to library and information professionals are indeed great. So are the opportunities!

Following this trend, I shall devote the most part of this paper to the

exciting area of multimedia/hypermedia information delivery and the new

opportunities for information centers in the 1990s will be further elaborated.

2. WHAT IS MULTIMEDIA/HYPERMEDIA?

In Vannevar Bush's famous article entitled "As we may think" published in the July 1945 issue of Atlantic Monthly, he projected that "information overload" would be a serious problem. It would be increasingly difficult for one to keep up with the latest knowledge in any given field. He described his vision of a device called "Memex," an electronic disk that could access any text of linking files within seconds (Bush, 1945). Although Memex was never actually developed, the foundation for a system now known as hypertext was laid. Bush's idea inspired two people about 20 years later -- Douglas C. Englebart of the Stanford Research Institute and Ted Nelson of Xa-nadu. Nelson coined the word "hypertext" in the 1960's which he describes as an non-sequential reading and writing that links different nodes of the text. Time limitation prevents me from presenting a detailed discussion on the development of hypertext and hypermedia beyond this brief mention.*

However, in order to facilitate the discussion on online multimedia/hypermedia information delivery, it is essential to provide a working definition of "multimedia/ hypermedia." At the recent blue-ribbon Multimedia Round Table Meeting at the University of California at Los Angeles, March 26-27, 1990, a small group of top-level multimedia experts gathered to discuss the future of multimedia developments. Not surprisingly, even this distinguished group found it difficult to define "multimedia." Instead of defining the term, some of them said that they prefer to consider multimedia as "mutual" media, or interactive media, or new media' and one stated that "multimedia embraces uncertainty as allies." All agreed that multimedia applications energize the senses.

Realizing the difficulty in offering an adequate definition, I have offered the following working definition to facilitate easier understanding of such applications:

1989 was one of the most significant years for the development of multimedia technologies, and the trend continues in 1990 and beyond. In 1989 alone, there were so many significant advan-ces related to various components of multimedia technologies -- computer processing, image pro-cessing, display technologies, digital audio, consumer electronics, telecommunications, scanning, digitized video technologies, etc. In 1990, the advances continue with DVI (Digital Video Inter-active), CD-ROM XA (eXtended Architecture), CD-I (Compact Disc-Interactive), and fiber optics (Chen, June 1989b; December 1989). In addition to being able to obtain multimedia information on a workstation, full color video images, text and data files can also be retrieved from PC-based image databases and transmitted down a standard telephone line.

Multimedia technologies are indeed ready for even more exciting multimedia applications in the new decade. There is a fundamental change going on in computing with the aid of very power-ful but low-cost new tools unlike any we have seen before. These tools enable us to produce easily exciting applications with multimedia information sources -- video, sound, music, and voice. Thus, the fading electronic boundaries among text, picture, sound, and moving image invite a reevaluation of the traditional ways knowledge is recorded, disseminated, utilized, and con-sumed. It has been predicted that the worldwide market for multimedia products and services will grow from $2.1 billion in 1989 to $15.9 billion in 1994 (Gale, 1989), and if the past is a good reflection on what is likely to come, the $15.9 billion could very well be under-estimated.

______________________

*For more thorough discussion on the topic, more general overviews of hypermedia/multimedia techno-logies, and extensive references, consult Chen's two recent books:

• Chen, Ching-chih. HyperSource on Multimedia/ HyperMedia Technologies. Chicago, IL: Library and Information Technology Association, November 1989. 237 p.

• Chen, Ching-chih. HyperSource on Optical Technologies. Chicago, IL: Library and Information Techno-logy Association, November 1989. 310 p.

Aside from the dynamic growth of computing technologies, it is important to take note seriously of the recent development in communications and networking. "Not only is electronic communication growing faster than communication through the traditional medium of print, but also the convergence of the modes of delivery (print, common carriage, and broadcasting) is bring-ing newspapers, journals, and books to the threshold of digital electronic communication." "In the past our various modes of communication were separate from each other, and the enterprises built upon them similarly distinct... But today the historically separate modes of communication are converging due to the adroitness of digital electronics. Voice, music, text, images, motion video, numerical data, and computer programs, are all in the domain of digital electronics. By means of digital electronics they can all be created, collected, organized, distributed, reorganized, copied, displayed or performed" (Brownrigg, 1990).

In this regard, as many of us are still in the midst

of developing campus-wide or region-wide computerized information network,

super-developing is going on. The recent National Research and Education

Network (NREN) in the US, supported by the Administration and with various

Senate and House bills proposed and to be reproposed, is bound to have

enormous worldwide implications even though it is established mainly as

an American national network. NREN is a telecommunications infrastructure

which would expand and upgrade the existing interconnected array of mostly

scientific research networks, such as NSFNET and regional networks such

as NYSERNET and SURANET, known collectively as the Internet. The aim is

to reach a 3-GB per second capacity by 1996, increasing current bandwidth

by over 2,000 times. To state this capacity in a simple way, this 3-GB/second

network could move 100,000 typed pages or 1,000 satellite photos every

second. It will be indeed an information superhighway! The

thought of com-bining this superhighway with the powerful multimedia technologies

for information delivery to every segment of the society is indeed both

mind-boggling and exciting!

4. HYPERMEDIA APPLICATIONS -THE CASE OF PROJECT EMPEROR-I

To follow-up the above discussions, I wish to share with you some of my own exciting R&D experiences related to the hypermedia applications of PROJECT EMPEROR-I since 1985. PRO-JECT EMPEROR-I is a cutting-edge computer and optical technology integration project on the First Emperor of China and its 7,000 plus life-size terracotta figures. The application is generic in nature, thus the techniques and processes can be transferred to other subject information delivery projects. PROJECT EMPEROR-I is an R&D project with numerous major project activities and products (see Appendix 1) developed on several delivery platforms -- MS-DOS systems for IBM PC and compatibles, Apple's Macintosh, Sun mini-computer, Digital Equipment Corporation microcomputers such as Professional 350 and MicroVAX. As time goes on, some applications are no longer functional due to obsolescence. For example, while gaining invaluable experience in the development of prototype interactive courses on DEC IVIS, those applications have been super-ceded by the hypermedia applications on either Mac or IBM's PS-2.

For this presentation, I shall limit the discussions

only on PROJECT EMPEROR-I's hyper-media applications. A few sample screens

are given here to introduce the complex and compre-hensive applications

at the tip of an iceberg. Although the subject topic is related to the

terracotta army and horses of the First Emperor of China, the application,

process and technological involve-ment are really rather generic, which

can be and have been applied to many other subject areas, in arts, culture,

science, technology and industry.

4.1. Applications on Apple's Macintosh

PROJECT EMPEROR-I demonstrates convincingly that powerful, flexible and user-friendly hypermedia applications can be developed on less expensive delivery platforms such as Apple's Mac SE and Mac II. Apple's HyperTalk was used to develop the Mac version of hypermedia applications, fully taking advantage of the rich and enormously large multimedia information bank stored on the set of two videodiscs -- moving video, still picture, audio in dual English and Chinese languages, music, descriptive text, primary expert commentary and interview sources -- as well as the large textual and database information stored on microcomputer. For the first time, we are able to deliver any of the chosen multimedia information, as we think, at speeds not pre-viously possible, generally as soon as we release the mouse after clicking it on a chosen icon. It is a true seamless environment where, behind the transparent HyperWeb environment, a system user can gather and link information easily from different storage media and sources to obtain his or her own desired information package, without feeling the pain and frustration of searching for infor-mation or waiting to obtain them. (Chen, June 1989a)

4.1.1. Application Modules

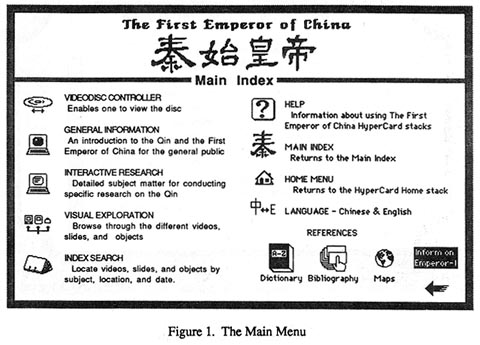

The Home Card of PROJECT EMPEROR-I's HyperMedia Guide will open the door for us to the "knowledge base" on The First Emperor of China just like we are entering the entrance to the Museum of Qin Terracotta Figures of Warriors and Horses in Xian and can expect to see the grandeur of the magnificent terracotta army of the Emperor. As we click on the arrow sign, the Main Index (or Contents of the knowledge base) will appear as shown in Figure 1. There are

several modules, each of which can be accessed by a simple click of the mouse. The heart of PROJECT EMPEROR-I's hypermedia application is the extensive interactive multimedia courses

which can be equated to over 60 hours of university study program. These courses can be access-ed at the following two levels:

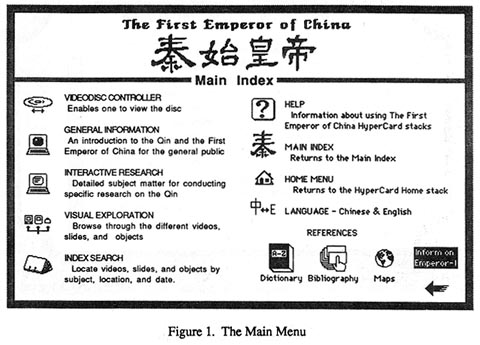

• The General Information courses which are designed for the general public and school children. When a topic, for example, "Introduction to Qin Shi Huang," is clicked or chosen, the browser will take the system user immediately to a video card, and the relevant video will start immediately to provide a 5-minute introduction to the Emperor. As the video is going on, the system user is able to browse the textual information displayed on the computer monitor, mani-pulate the video showing, or ask for additional information, such as an interview with a subject expert on the chosen topics, relevant slides on the subject, and additional textual information. In addition, one is able to either print or make notes on any thing as one thinks (Figure 2).

• The Interactive Research module works in

a similar way to that of the General Infor-mation module. The Interactive

Research courses were modeled after an extensive two-semester graduate

study course outline. They are intended to provide a student and/or researcher

with much more detailed subject treatment on a chosen topic. Thus, the

subject topical areas can have several levels of subdivisions. Each topic

is presented with one, two or all of the three types of informa-tion sources

-- textual information, visual (slides or videos), and interviews. When

slides are chosen, database information and descriptions of the slides

together with information sources can be retrieved easily as well.

Aside from the above, there are several other useful modules as well:

• Videodisc Controller enables one to retrieve the visual information on the disc at Level I interactivity (this means that one is able to play the video at normal speed, or to scan faster or slo-wer, or to go forward or backward one frame at a time).

• Visual Exploration enables one to quickly and easily explore the still and video images, and also obtain videos with zooming-in, zooming-out, and rotating effects.

• Index Search is essential for obtaining database, description, and related textual informa-tion on any given still image or moving video segment. There are six ways of searching -- by date, location, type of material, source of information, subject, or a combination of them. The Subject Index essentially maps out the hierarchical structure of the entire subject.

Aside from these modules, commonly applicable to all searchable information are the "Re-ferences" which can consist of all types of reference tools available in a library. We have chosen only three at this time for prototype development and demonstration. It is our belief that if three can work smoothly in the system, then any number of types of sources available in the library can be accommodated as well. These three types are:

• Dictionary • Bibliography • Maps

For Bibliography, not only relevant bibliographic citations are given, but also full text retrieval can be performed immediately, provided there is no copyright difficulty. For Maps, they are available from macro-geographical maps of an area to the plan of the site showing the line up of the 7000 terracotta figures, and images of any given part of the plan can also be immediately retrieved together with the associated information.

4.1.2. The System's HyperWeb Links

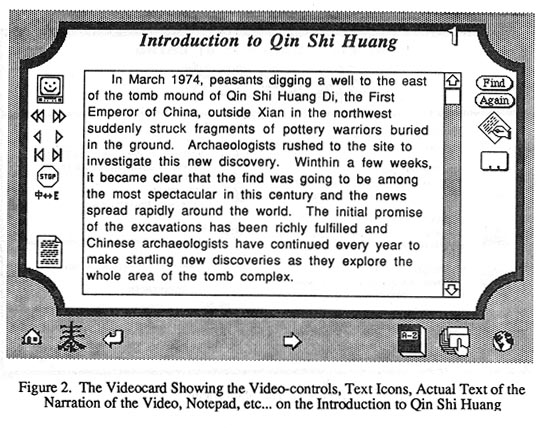

This system is transparent to users who can truly access quickly and painlessly the massive amount of multimedia information, gathered and synthesized together. We have indeed achieved the non-sequential browsing, reading, and writing. The simpler and more user-friendly the system is for users, the more complex the links among different nodes of texts, files, images, and audios are. Take the Interactive Research module as an example; we have developed seven courseware for the students and professionals in this subject field. The knowledge base is arranged in a hier-chical structure, with each broad subject topic (which is considered a course in our project) further subdivided in numerous sub-, sub-sub, and sub-sub-sub-sections whenever appropriate. Thus some topics many have five levels of sub-sections. When we go down one level of sub-divisions under topic, the complexity of the HyperWeb links increases sharply as illustrated in Figure 3. One can imagine what the web would look like when it is truly representative of the current course structure with multiple levels of divisions under each topic. Remember also that we are only discussing the Interactive Research module, and the system has multiple modules, as described earlier, which are all linked together in a cohesive way.

4.2. Multimedia Applications on Other Delivery Platforms

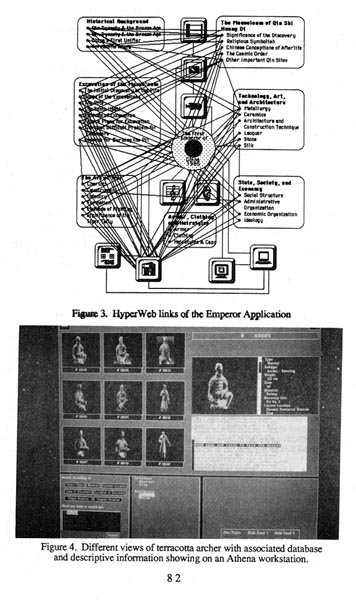

In addition to more than 60-hour interactive courseware available on Mac II, multimedia application courseware or demonstrations are also available on other delivery platforms. Multi-media applications are being experimented with at both DEC's MicroVAX under the MUSE system in cooperation with Project Athena of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Figure 4 shows how still images fulfilling the same search requirements can be displayed on the same

screen, and any one of them can further be enlarged

together with descriptive and database infor-mation provided concurrently.

Further information on this application can be found in Chen's article

in Academic Computing (Chen, March 1989). At MIT, similar multimedia

applications are

The most recent joint development of a demonstration with IBM in using its latest Linkway 2.0 version and the M-Motion card on IBM PS-2 extends the exciting multimedia applications to the IBM delivery platform. Figures 6 & 7 show similar information described for the Apple's Mac system presented on IBM screens. The user can move the mouse to any graphic icon either on the left side panel or any one of the nice graphic video icons and retrieve desired information almost instantly in the similar way as described for the Mac system. When the graphic icon is chosen, the related video or slide will be shown immediately on the full screen, and related textual information or database information would be shown in an overlay window.

In addition to the information on the subject of

PROJECT EMPEROR-I, information seekers can access other either related

or non-related multimedia information as well, as long as they are linked

together. For example, Figure 8 shows that "The First Emperor of China"

is only one of the 6 subject icons on the IBM Linkway's prototype demonstrations.

Thus, a system user can easily get out of the Emperor subject and obtain

multimedia information on either minerals or mam-mals or Hurricane Hugo...

5. TECH2000 AND THE VISUAL INFORMATION AGE

Interactive Video Industry Association (IVIA) cosponsored its Leadership Forum on "Productivity and Learning in the Visual Information Age" with Business Week at the newly

completed TechWorld in Washington DC, November 29-30, 1989. At that conference, it was stressed that the technological environment has had a dramatic effect on us and will continue to affect us as we enter this "visual information age." We are required to develop our

future and see it with a new lens rather than distorting the picture with the lens of our past. There is a need for a fundamental shift from text-based to media-based information. While multimedia technologies are powerful and versatile, their greatest potential lies in the effect they could have on the way we learn. In this visual information age, educators are forced to

redefine the meaning of teaching and learning, and without exception, librarians and information professionals are forced to redefine the meaning of information access and delivery. Clearly the keywords related to productivity are online, on demand, and interactivity. Multimedia technologies have changed how we demand information, and for the first time, a learner is learning how to learn and an information seeker is learning how to ask for information. The information seeker can demand his/her needed information in a non-linear way, and to include not just print-based infor-mation. Multimedia applications are available to provide the learners with multiple doorways for exploration and meaningful participation, and to information seekers with only the relevant infor-mation prepacked and screened. They also offer an "engaging experience" in the context of the user's information needs.

To illustrate these concepts and to provide a "hands-on" showcase for the latest in interactive multimedia, video, and information and communication technologies, the world's first museum of interactive multimedia, TECH 2000 Gallery, had its preview opening on November 28, 1989 at the new TechWorld Plaza, and has been open to the public since February 1990. More than 70 com-panies have committed advanced interactive programs and equipment demonstrating the power of the new media in areas as diverse as education, training, the workplace, information management, and entertainment. TECH 2000 exhibition includes an impressive array of applications each of which demonstrates the versatility of interactive multimedia. Aside from some impressive premier applications in the areas of arts, humanities, and social sciences -- such as Guernica, the National Geographic Society GTV and PROJECT EMPEROR-I -- the subject matters of the selected appli-cations span all areas including:

• Health Check • Make the Telephone Work for You

• Rigging and Lifting • DuPont Refrigeration

• Federal Express Aircraft Maintenance • Executive Work Station

• Welding Simulator • Intravenous Therapy

• Combat Trauma Life Support • Field Guide to Insects and Culture

• Exotic Plants • Earth & Space

• Bio Sci • Ninth Grade Science Program

• Life Story • Genesis

• Whole Earth CD

The list has expanded rapidly since then. Each application demonstrates how multimedia technology enables us to get ready for the real world, and to be able to learn and to retrieve needy information with real tools. Aside from TECH2000, many more exciting multimedia applications are also covered in literature (Chen, November 1989a and November 1989b). These include appli-cations in all kinds of subject areas -- ranging from travel marketing and tourist information, to business & industry, automobile industry, clinical situations, dental medicine, AIDS information, medical education, planet, telecommunications, high school science, military, and space flights.

Clearly, computers have been used to run a full range of applications in many organizations including university departments. For example, in the field of higher education, instead of the earlier computer-assisted instruction applications of the 1950s and 1960s, which "never work, fly, sing, swing, or walk," the present multimedia applications offer higher education all kinds of possibilities. As stated by the editor of Academic Computing in his editorial of the October 1989 issue:

"The effect of seeing animated and enthused chemists,

linguists, historians, entomo-logists, physicists, mathematicians, musicians,

and neuroanatomists, shoulder by shoulder, bombarding the sight, hearing,

and touch of strollers-by with their discipline specific riffs left attendees

with the feeling that something different is going on here. And, indeed,

it was different."

The widespread use of multimedia technology for end-user information delivery could potentially have a great impact on library and information systems and services. During the 1960s and 1970s, automated information systems were mainly designed to serve staff needs by replacing cumbersome manual systems, filing, and recordkeeping processes with inventory control systems mainly either "borrowed" or derived from the business community. Information clientele were seldom considered as the primary users of these systems. In the 1980s, service to information clientele became increasingly more important for information systems, and this prompted the deve-lopment of various online databases and public access catalogs such as OPAC. As we enter the visual information age of the 1990's, it is expected that information systems will have to provide even more dynamic and demanding services to patrons who are increasingly more sophisticated. Thus, printed-based or text-based information systems are no longer satisfactory. The users are becoming more and more demanding for information in all formats -- text, images, and audio --

for information as they think.

In 1986 when I discussed the current day's libraries in the midst of a period of unprecedented change and adjustment, I advocated the need for libraries to shift focus to include the following directions in addition to our basic functions (Chen 1986):

• From library-centered to information-centered,

• from the library as an institution to the library as an information provider, and the librarian as a skilled information specialist functioning in an all-related information environment,

• from using new technology for the automation of library functions to utilizing technology for the enhancement of information access not physically contained within the four walls of the library,

• from library networking for information provision to area networking for all types of information source providers.

Basically, these directions have not changed since

then. In order to meet the complex and diversified information requirements

of the academic/research/industry community, modern day scientific and

technical information centers must utilize flexible, distributed systems

to provide needed information at the workstation level. These systems must

be able to support access to multimedia information in a variety of formats

as well as materials which are not confined within the four walls of the

libraries or information centres. Since print-based information provision

alone can no longer satisfy the information seekers' needs, multimedia

information delivery is essential. Furthermore, in light of the continued

exponential growth of information, the increasing demand for information

from a knowledge-based society; and the tremendous financial and space

constraints on actual information source acquisitions, the networkingof

these information systems into national and global information networks

is critical.

6. THE FUTURE

The expectations of the current technology of integrated multimedia information delivery system inevitably greatly expand the traditional system functions and have increased sharply infor-mation access for its users. A comprehensive information system of tomorrow will be one that is evolving far beyond a text- and/or data-based system. It will definitely be multimedia with capa-bilities for non-sequential linking of not only related, but also non-related information sources.

Many of you know that the MIT's Media Lab is known for its provocative role in developing future multimedia systems. Let me share with you just the titles of a few talks presented by the key speakers at the two-day Celebration Conference on the Media Laboratory (MIT)'s 5th Anniversary on October 1-2, 1990 at MIT:

• "From the Media's Mind to the Mind's Media: Turning Learning Upside Down,"Seymour Papert

• "People will Like Computers More When Computers Act More Like People," Marvin Minsky

• "Good-bye to Mass Communication: So Long Broadcast, Newspapers, Books,"

Nicholas Negroponte

• "Television of Tomorrow: Signals with a Sense about Themselves," Andrew Lippman

• "Music in the Next Millennium," Tod Machover and Barry Vercoe

I don't have time to describe the key points of each of these talks, yet, it is not difficult to guess the content. On the other hand, how do these scenarios compare with our current library and information related environments? Are our library and information computers acting more like people? Or, are we telling our system users that they have to conform to our ways of design otherwise they won't be able to retrieve relevant information? Isn't it true that we, library educa-tors, have to spend a couple of semesters to teach retrieval techniques for even just print-based information? We know that we have a very long way to go!

Yet, those systems talked about by some of these futurists are really not future systems. I have been privileged to see some of them, which either are being developed or have been developed, though they may be far from perfect. These experimental systems are mostly visible in non-library application areas.

It is worth mentioning that when Nicholas Negroponte entitled his talk

"Good-bye to Mass Communication: So Long Broadcast, Newspapers, Books",

he did not mean to say that there will be no broadcasts, newspapers, and

books. He contended that broadcasts, newspapers, and books will be very

different from what they are today. He emphasizes that computers will be

developed to "know" their users, read for them, and screen the diversified

information sources for them. They will also be able to meet their users'

information needs automatically from a vast array of sources through the

great variety of information delivery systems which we may take for granted

in tomorrow's society. He predicts that individuals will increasingly rely

upon the use of "filters" to select out the most needed information. Before

the end of this century, how many of our library and information systems

will be able to "filter" for our users? An interesting question indeed!

It should be an understatement to say that this is an interesting time

for library and information professionals!

REFERENCES

Brownrigg, Edwin, "Developing the information superhighway: Issues for libraries," Commis-sioned paper for the President's Program of Library Information Technology Association Meeting, Chicago, Il, June 1990. p. 1.

Bush, Vannevar, "As we may thing," Atlantic Monthly 101-108 (July 1945).

Chen, Ching-chih, "As we think: Thriving in the HyperWeb environment," Microcomputers for Information Management 6 (2): 77-97 (June 1989), and concurrently published in the Proceedings of the 2nd Pacific Conference on New Information Technology, edited by Ching-chih Chen and David I. Raitt. W. Newton, MA: MicroUse Information, May 1989. pp. 37-52.

Chen, Ching-chih, "The First Emperor of China's ancient world uncovered: From Xian to your electronic screen," Academic Computing pp. 10-14, 54-57 (March 1989).

Chen, Ching-chih. HyperSource on Multimedia/HyperMedia Technologies. Chicago, IL: Library and Information Technology Association, November 1989. 237 p.

Chen, Ching-chih. HyperSource on Optical Technologies. Chicago, IL: Library and Information Technology Association, November 1989. 310 p.

Chen, Ching-chih, "Libraries in the information age: Where are the microcomputer and laser optical disc technologies taking us?" Microcomputers for Information Management 3 (4): 253-266 (December 1986).

Chen, Ching-chih, "Multimedia technologies await the coming of a new decade," Microcomputers for Information Management 6 (4): 303-313 (December 1989).

Chen, Ching-chih, "Why current technology is ready for multimedia and hypermedia application," Microcomputers for Information Management 6 (2): 135-145 (June 1989).

Gale, John. Micro Multimedia. Alexandria,

VA: Information Workstation Group, 1989.

Appendix 1. PROJECT EMPEROR-I's Activities and Products

The production of videodiscs

A set of two 12" NTSC CAV videodiscs, entitled "The First Emperor of China: Qin Shi Huang Di, " was produced in 1985;

The development of interactive multimedia courseware for both general public and students and researchers.

Developments in this area include:

• Prototype courses for DEC's IVIS systems

• Sample courses for IBM compatible PC systems in 1987-88 using DIRECTOR software

• Hypermedia applications on Macintosh, including the latest Mac IIs. Both English and Chinese versions have been developed

• Multimedia application on DEC MicroVAX is being experimented in cooperation with Project Athena at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

• Demonstration course development with IBM on the use of latest Linkway 2.0 and its M-Motion card

• Further development of Mac system using the Color Space card from Mass MicroSystems

The creation of electronic image databases

• Using Image Concepts' C-Quest for IBM compatibles

• Cooperating with SOPHIATEC of Nice, France in using SOPHIADOC for IBM compatibles

• Using HyperTalk in developing in-house image database system for Mac II

• Using Image Understanding System's OASIS Software for Sun Microsystems' Sun 3-160 minicomputer

High-resolution image digitization and electronic imaging

This application is being developed on a Sun 3-160

Converting/creating large textual files and scanning/digitizing images

Using MicroTek's MSF-300G image scanner, INOVATIC's

optical character recognition software, ReadStar II Plus, and VersaScan

software.