La Organización de una Red de Información Común

Ruth Stanat

Strategic Intelligence Systems, Inc.

New York, NY 10016, USA

Abstract: In todays global business environment, executives are faced with the problem of obtaining rapid access to business information which is both internal and external to the organization. This paper defines a step-by-step approach on how to build a shared infor-mation network.

Resumen: En la arena de los negocios mundiales acutales, los ejecutivos enfrentan el problemas de obtener un rápido acceso a la información comercial, que es tanto intraem-presaria como exterior a las empresas. El presente trabajo define un enfoque paso a paso sobre cómo organizar una red de información común.

Jan Carlzon, Scandinavian Airlines

In todays business environment, it goes without saying that information can make or break a company. Almost any business information may be termed "strategic intelligence," depending on how it is used. Often-times, the information includes valuable data on your competitions finances, manufacturing processes, products, or advertising and promotion budgets. Depending on various definitions, however, strategic intelligence can also involve areas such as marketing research, stra-tegic planning, legal affairs, field sales, and so on. We may therefore define strategic intelligence as the gathering, synthesis, and dissemination of strategic and tactical information in a systematic and timely manner for the purpose of developing a shared information network.

2. WHY SHARE INFORMATION?

Most organizations experience the "hoarding of intelligence." No matter what size the com-pany, corporate executives have begun to realize that information is power. Nowadays, as the size of organizations fluctuates, less and less information is documented or catalogued. Yet, the hoard-ing of information is inherent to the management system in both large and small companies because managers are rewarded for innovative ideas and original thinking.

The hoarding of intelligence is exacerbated with the increased size and complexity of an organization. Large corporations that are decentralized and have numerous operating divisions are faced with a tremendous amount of duplication of effort. In one company, more than six different departments generate studies on the same topic area at the same time. How many times have you just finished looking up some information to discover that a report in another department already contains the information? This hoarding of intelligence puts companies at a competitive disadvan-tage. Companies that can quickly retrieve internal information and efficiently synthesize and disseminate external information have an advantage over those organizations that cannot. Further-more, each manager or executive is a data base of information, with years of functional and indutry expertise making him a resident expert on certain topics. Getting access to your co-workers or subordinates areas of expertise requires that you tap into their data bank of information, which is stored in their brain. Thus, the infloglut factor has led to the increased emphasis on and impor-tance of information sharing within organizations.

3. THE EVOLUTION OF CORPORATE INTELLIGENCE SYSTEMS

Many executives from both large and small companies are often threatened by the term "intel-ligence systems." Most corporate executives feel a strong aversion to building large-scale systems that involve significant capital and human resources and that may prove to be of little value to the company. For this reason, it is far more effective to focus on building a program that offers high impact on bottom line results of the company.

The most successful programs are not initiated with building of large-scale systems. They often start with a department or a person who has the charter of gathering and disseminating busi-ness or competitive intelligence, for example, marketing research, strategic planning, controllers, the information center, or an individual in an operating division.

Whatever the specifics of the job function, the individuals involved have to quickly develop a methodology for the ongoing scanning, synthesis, and dissemination of this information to various departments. In a small business, the marketing or sales department typically performs this func-tion because it is closer to the customers in the field. In many large organizations, the marketing or sales department can actually "feed" information from field settings into a corporate intelligence system.

3.1. A Survey On Information Needs: How Does Your Company Stack Up?

A survey conducted over the past five years by Strategic Intelligence Systems, Inc. examined the information networking needs of a majority of the USA Fortune 100 firms. Specifically, the survey analyzes responses from phone calls, formal and informal interviews, and actual audits or "needs analysis" projects. The survey was unstructured at times. The exact questions, however, remained constant and the departments varied from firm to firm. The results of the survey were derived from the responses of mid-to-senior level executives from the following departments:

• Strategic planning • Financial planning

• Marketing research • Corporate information center

• Product development • Corporate library

All respondents answered the following questions:

• What department within your firm is responsible for competitive intelligence gathering or functions as a centralized repository for information?

• Do you have a formalized process for the systematic gathering of intelligence on a routine basis and a mechanism for distributing or accessing the information?

• What is your annual budget for this type of information, including staff resources, salaries, purchase of outside information sources, purchase of international information?

• What do you spend on outside consulting services?

• What happens to internally generated documents within your organization?

• What are your current and future information needs?

• How frequently do you need this type of information?

• In what format do you need the information?

3.2. Results of the Survey

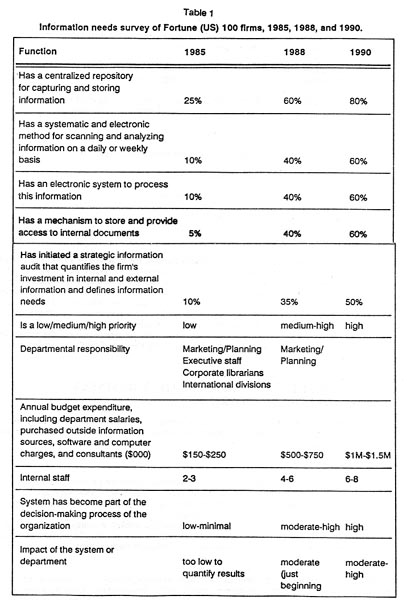

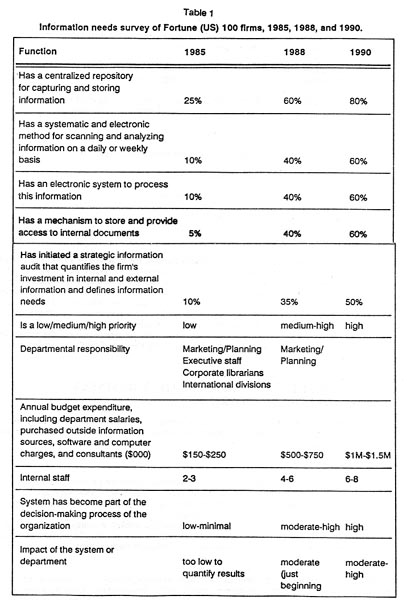

The following sections outline the survey results through the first half of 1988. For perspec-tive, data are included from 1985 to show the growth of business intelligence networks. The data illustrate that large organizations have realized the need for an information center, which has be-come a centralized repository for information and the lifeline of these organizations. The data in Table 1 signifies the "enlightenment" of management over the past five years toward this concept.

The table also shows that a centralized intelligence network was not considered an integral part of most major firms as late as 1985. As corporate staffs have thinned out during the past three to four years, more firms have recognized the need for such a network. Of significance is the growth of electronic systems to 40 percent of the Fortune 100 firms. By the end of 1990, we project this figure to reach 60%.

4. PHASES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF A BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE NETWORK

The following four phases are involved in developing an intelligence network. They can serve as a benchmark for organizations implementing a network and are especially useful for those "stuck" at a certain phase.

Phase 1: Corporate Awareness

In this phase, the company does not have a formalized process for gathering and synthesizing external information from published sources. Additionally, the company does not maintain an in-ternal library of source documents that are distributed within the organization. Typically, these documents are in the form of interoffice memos, competitive information obtained from sales representatives, and internally published studies on a particular market or competitor. The organi-zation does recognize the need for developing a shared information network that is derived from internal and external sources. In addition, a strategic information audit is conducted during the cor-porate awareness phase.

Depending on various factors, such as the culture of the organization, its mission, and its current business position, corporate awareness may be difficult to develop. Gaining awareness and acceptance of the need for an intelligence network may depend on the efforts of an "internal

champion" or department to make management aware of the need for such a network. (An "inter-nal champion" simply refers to someone who develops awareness and initiates the process

of developing an intelligence network.)

Phase 2: Establishment of a Department or Process to Gather Information

In this phase, the organization identifies a department or group of people (or functional area) responsible for gathering internal and external intelligence. Principally, the departments activities are as follows:

• Formation of a centralized corporate library

• Distribution of hard copy daily clippings from published sources

• Distribution of a newsletter

• Sporadic generation of reports that profile or analyze the competitors of the organization

• Occasional use of external information providers

• Heavy use of external consultants on per project basis

In most of today's corporations, the actual department most closely associated with these activities is the corporate library or information center. During this phase, the library or inform-ation center establishes a process for gathering internal and external intelligence sources. Although these departments have become vital settings in most corporations, the intelligence-gathering effort has become prevalent across various business units and divisions of an organization.

With the shrinking size of internal staffs, the intelligence-gathering process is usually aug-mented by contracting with external research firms that specialize in developing intelligence pro-cedures. Nowadays, many of these firms have become valuable resources to organizations during this phase.

The most formidable task during this phase is to integrate internal and external information sources in a manner that is cost-effective, easily accessible to management, and most important, actionable.

Phase 3: Development of an Electronic System

Now that the organization has developed a process for gathering intelligence and information sharing is a major objective, the next step is to develop a business or corporate intelligence network that combines critical internal documents and captures external information on a systematic basis. During this phase, the company outlines the information architecture or the actual blueprint of the intelligence network.

Because the objective of the network is to have intelligence available throughout the organi-zation, the network involves multiple user departments and generally has a complex information architecture. In this phase, the company actually has an operational system with select users. The system will continue to evolve until it reaches Phase IV.

Phase 4: Development of a Global Electronic Network"

In this phase, all functional departments are actively using the system, which has evolved into a global electronic intelligence network. The following list outlines what such a global elec-tronic network can accomplish and the inputs and outputs of such a system:

• An electronic system with more than one hundred users on the system from all functional departments and divisions:

• A system that is pro-active and provides relevant and timely intelligence to the end user

• A systematic method for scanning and synthesizing information on a daily, monthly, or quarterly basis, according to the specific needs of corporate staff and the operating divisions

• A method for putting critical internal documents into the system

• A method for capturing field sales and manufacturing intelligence and incorporating this information into the system

• A source of several information products for corporate executives (data base access, news- letters, quarterly reports)

• A mechanism for periodic review of the system and process that constantly evolves to meet changing business conditions

• A cost-efficient system that reduces duplication of effort between departments and between external information suppliers and consultants

• A system that becomes part of the planning process and serves as critical input for decision making

5. THE GOAL: A CORPORATE INTELLIGENCE NETWORK

"Corporate intelligence network" sounds like a very fancy and upscale title that only the Fortune 50 firms could afford. Every company, however, regardless of the size or complexity of organization, has a need to develop a process for its information gathering and dissemination. Smaller firms, in particular, have a need for a process to track their business environment, their competition, their markets, their field sales activity, and new developments in technology. For these firms, an intelligence network, no matter how simple in design, can be the key to survival.

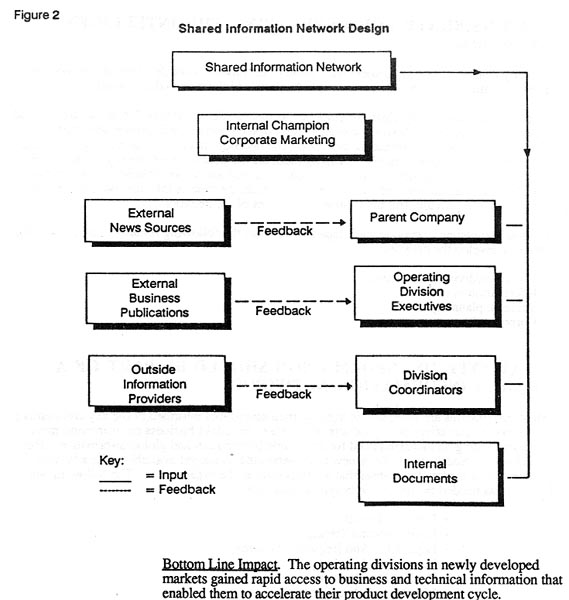

6. SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE:

From a broad perspective, "system architecture" can

be defined as the visual representation of a system through which information

provided by source documents is changed into final docu-ments. Clearly,

the purpose of systematizing information is to maintain the basic elements

of input-process-output. This allows an organization with a large infrastructure

to sustain itself. In my experience, I have found no single architecture

appropriate for the development of a shared in-formation network. The flow

and circulation of information is largely based on the structure of the

organization, as well as the corporate culture. Figure 1 depicts a simple

system architecture in

which a data base and other forms of information are derived from source documents.

In this simple example, internal and external information sources are pulled together to create a data base. Such a data base, which increases in value over time, can become part of a corporate

wide intelligence network and the center for distribution

of information in various forms (for example, company newsletter and quarterly

reports).

7. RESPONSIBILITY FOR DEVELOPING THE INTELLIGENT NETWORK

In many instances, one department may assume responsibility for developing the network to minimize duplication of effort and maximize productivity of information dissemination.

Unfortunately, there is no clear-cut guideline as to what department or functional area should

be responsible for this task. Clearly, the organization of the company will dictate which depart-

ments are well-positioned to execute the network. The decision involved in delegating this respon-

sibility can be based on various factors. Among them are the actual size of the organization, whe-ther the organization is centralized or decentralized, the actual job responsibilities or job descrip-tions of each functional department within the organization, the type of information that the intel-ligence network will provide, and the strategic objectives of the network.

In most companies, corporate staff departments from the following functional areas have the capabilities to develop the network:

• Corporate/division marketing

• Information systems

• Strategic planning

• Corporate library

8. WHAT TYPE OF INFORMATION SHOULD BE PART OF A SHARED INFORMATION NETWORK?

Most corporations are interested in keeping their employees informed of the key competitive or business events that affect their products or services. In todays business environment, most executives are finding an increased need for actionable information and global information. This information can be readily available or new information that is not yet available. The key notion here is to centralize the key topic areas that are important to the organization. The following are broad topic areas needed by almost every type of business:

• Environmental Trends

• Legislative And Regulatory Events

• Competitor Activity

• Product Development

• Mergers and Acquisitions

• International Events

The design of a corporate intelligence data base

is the most important element of the system. Some companies spend millions

of dollars on elaborate corporate intelligence data bases only to find

out that it is easier to use file drawers to retrieve the information that

it is to navigate the data base. The data base, however, should reflect

how the management of the organization views the business. Key variables

such as the lines of business, competitors, markets, and products should

be well thought out.

The mature operating divisions now had an organized process by which to monitor their competition on an ongoing basis. The greatest value was derived from information on competitors in the Far East.

Reduced duplication of effort was cited in areas of new business or market development projects.

9.1. How to Get Started

According to Ed Rubinstein, Project Director, Strategic Intelligence Systems, Inc., "the biggest problem is deciding how and where to start an intelligence network." By now, you are probably thinking that a business intelligence network is exactly what your company needs to become an "intelligent" organization. You may be asking the question, How do I get started? Again, the need for and benefits of this type of program depend on senior management support and a coordinated effort of several departments. Sometimes, one department in a corporation will suc-cessfully initiate its own program or system. After the department has attained a desired level of awareness and installed a working system that is constantly evolving, other departments see the value in the system and either want a similar one or want to share in the information network.

Step 1: Identify The Internal Champion

Someone has to assume the role of internal champion to implement the corporate intelligence system. Having observed several executives functioning in this capacity, I can assure you that the task is not an easy one.

The success of a corporate intelligence network is dependent on the ability of the internal champion to coordinate with senior- and middle-level executives in the operating divisions, the marketing research staff, the planning staff, the information systems staff, and other functional areas such as research and development and manufacturing. Internal champions frequently emerge from the following functional areas:

• Strategic planning • Information systems

• Corporate marketing • Research & Development

• Marketing research • Manufacturing

• Controllers office • Corporate development

Recently, the title "Chief Information Officer" (CIO) has been placed on many organization charts. Generally, CIOs are likely to be the best internal champions. With the need for global and field intelligence, the function of the CIO will be critical to organizations during the 1990s and beyond.

Step 2: Organize the Internal Effort

Given the nature of these systems, their success or failure is contingent on the ability of the internal champion to marshal the efforts of key people in corporate staff or operating divisions. Al-though each situation may differ, the following functional areas are typically involved in the effort:

• Strategic planning • Information systems

• Marketing research • Corporate library

• Controllers office • Operating division management

Step 3: Develop a Work Plan

The work plan serves as a conceptual time frame for the development of a corporate intelli-gence network. It may also entail organizing a task force to develop such a plan. The most successful business intelligence networks are executed against a well-thought-out work plan that secures a commitment from senior management. In addition, the plan should be based on the immediate and long-term objectives of the organization.

How many times has your company embarked on the development of a new process or sys-tem, only to find out, hundreds of thousands of dollars later, that a simple less complex process would have sufficed? because corporate intelligence systems are still a "blind spot," it is wise to proceed cautiously and implement a phased approach. Many of my clients term this process a "pilot" project, and should the system be successful, then incremental investments are made. Costs can be carefully controlled through a phased approach as follows:

Phase II Analysis of Needs

Phase III: Design of the Prototype

Phase IV: End-User Feedback of the Prototype

Phase V: Implementation of the System

During this phase, a series of meetings should be held to identify short- and long-term goals for the system. These discussions should be well thought out and strategic in scope, that is, they should be based on the immediate and long-term objectives of the organization. The more stream-lined this process is, the less likely it will be put off.

In some organizations, "task force paralysis" occurs. In this scenario, the internal champion has been identified and a work plan has been mapped out, but the planning phase has been stymied by corporate bottlenecks. Such pitfalls are described later in this chapter. The planning phase should be executed in a four-to six-week time frame with a brief planning document or PERT chart representing the deliverables to senior management.

Step 5: Conducting the Strategic Information Audit

This phase should entail conducting internal interviews, analyzing the results, and presenting the findings to senior management. Depending upon the availability of internal executives, this phase should take between four and six weeks. The deliverable is a cohesive document that ana-lyzes the survey results, along with a "blueprint" or information architecture of the corporate intel-ligence network.

Step 6: Develop A Prototype

Rome was not built in a day. Neither will be a corporate intelligence system. These systems should be designed with significant flexibility to accommodate changes in the corporation and its lines of business. Ideally business intelligence systems should integrate both internal and external information. Thus, prototyping is absolutely necessary to determine if the system is flexible enough to meet the short- and long-term needs of the company. Such a system is a strategic intel-ligence network.

The prototype for a business intelligence network acts as a small-scale offering or test market of the network. At this point, the internal champion and the task force must decide whether to develop the prototype in-house or hire on outside firm. The average time frame for this process is four to six weeks.

End users also should be involved in the design and development of the prototype. Just as a manager or administrator would set up his or her own filing system to be able to find specific in-formation, the users of the system should have input into the content and format of the data base.

Step 7: Obtain User Feedback

Following the development of a prototype and selection of the initial content of the intelli-gence network, the internal champion of the task force must obtain end-user feedback and make modifications to the system, where and if necessary. Such modifications may include allowing for refinements of the actual format and data base design. For instance, many executives prefer infor-mation that is summarized by key points, rather than in general prose or paragraph form.

Although some users may find the prototype of the intelligence network informative, in some instances, they think the information on the networks insults their intelligence. Hypothetically, this might result in the question, How do you convince the product manager of a leading national brand that a business intelligence network will improve his function and bottom line profits? This is not an easy assignment for the internal champion and the task force and is where the notion of value-added information services comes into play. Generally, a business intelligence network increases in value when the information includes some form of analysis, which transforms a shared informa-tion network into a business intelligence network or strategic intelligence system.

This analysis might answer the following questions:

• What might this event or news mean for the company?

• What might this event or news mean for the business unit I represent?

• How might or organization or our competitors respond to this event of news?

• What other developments or functional areas might be affected by this event or news?

Such analysis may be performed by the group responsible for the prototype network. In todays business environment, however, a growing number of organizations are using the services of external information suppliers. The initial feedback of the system best serves the internal cham-pion and the task force with a formal survey distributed to the end users of the network.

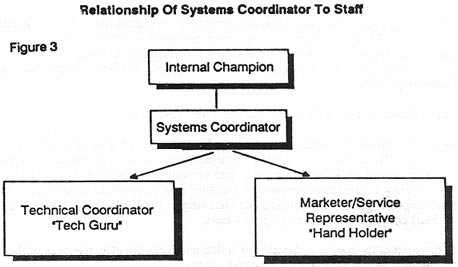

Step 8: Develop The System

Following the development of a prototype, it is appropriate to select the hardware and soft-ware if management determines such an information system should be developed. It the prototype was successful, this phase may involve transferring data to a large-scale computerized system. This phase should also include the training of select users of the system. The person chosen to train the users should be a member of the task force and may be called the systems coordinator.

Step 9: Roll Out The System

Once the system is in place, additional users should be added. In this phase a communications program should be developed to increase the number of participants. The communications pro-gram need not be expensive (see Figure 3 for the relationshio of Systems Coordinator to Staff).

The following are some suggestions for communications programs for the system:

• Presentations to senior management

• A corporate newsletter that highlights the system

Step 10: Establish A Support Structure for the System

A support structure evolves over time and is critical to the long-term success of the network. The support structure contains a help or service function built into the system that assists the inter-nal champion in handling user feedback and allows for modifications to the content of the network. As more valuable information is added to the network, additional users will access the system. This support structure constantly entails user feedback and can result in modifications to the system on an ongoing basis.

At a relatively simple level, a support structure for the system can be put into place by esta-blishing two components:

1) A job function or department within the organization that is responsible for providing users with system support, in essence a troubleshooting function,

2) A "hot line" that users can telephone for technical support and for assistance with infor-mation content.

In most organizations, the actual support structure of a shared information network is either small or nonexistent. In some organizations, however, such a support system can be quite large and sophisticated.

Step 11: Promote Evolution of the System

Strategic intelligence systems or networks involve continuous evaluation and modification. Because they are tied to the business environment and are content-driven, they must be continually changing. Moreover, the internal champion is often slated for a new job function (oftentimes a promotion) following the execution of such a system. Thus, it is important that the internal cham-pion train a successor during his one-to-two year implementation period.

9.2. Pitfalls

These eleven steps sound so easy. Having personally executed them, I can honestly say that this is not an easy task. However, these systems have demonstrated bottom line results, and are viewed by many organizations as necessary for long-term success. Although some pitfalls may seem like major obstacles, the actual cases presented throughout this book reveal that major corpo-rations have overcome them.

9.3. How to Measure the Effectiveness of the Network

According to Citibank, its system "brings the efficiencies of a flat organization without Citi-bank being one." These benefits - the ability to quantify productivity savings, block a competitors moves, or bring a product to market quicker-illustrate the effectiveness of the system. There should be a thorough semiannual review of a network, rather than a quarterly review, to allow a time frame long enough to pinpoint tangible benefits or savings. Typically, such a review entails the use of hard copy questionnaires or personal interviews.

For organizations that have developed an intelligence network, the effectiveness of the net-work can be measured by answering the following questions:

• Are the goals and potential benefits of the network well-communicated?

• Does the network have support from top management and several key functional areas (for instance, field sales, market research)?

• Can the network be modified or adjusted as the objectives and goals of the organization change?

• Are the people involved in the development or ongoing maintenance of the network moti- vated? Do they generate new ideas?

• Does the network effectively and efficiently gather and disseminate intelligence?

• Does the network provide pertinent information that can be transformed into actionable decision making?

• Does the network contain built-in measures for obtaining feedback?

• Are there previsions for reviewing and evaluating the network on a systematic basis?

_____________________________________________________________________________

9.4. Case Study: "Citibank Climbs Out of the Box"

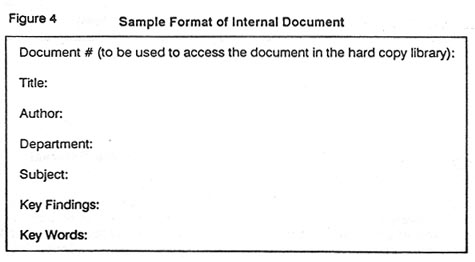

Five years ago, Citibank N.A. recognized the need to develop an intelligence network which included the integration of their internal and external information. As such, the bank had several marketing and research libraries which had volumes of publications, research reports, planning documents, clippings, etc. A simple bibliographic format was designed to input abstracts of the select documents into an databases for mounting on their intelligence network and for distribution to their marketing and planning executives. A rigorous screening procedure was implemented to determine which documents should be abstracted for the system (refer to "The Intelligent Corpo-ration," Ruth Stanat, Amacom Spring 1990). Additionally, the data format included a section for "key findings" which enabled the user of the database to determine the relevance or value of the document for future referral (Figure 4).

To capture information from their external business environment, Citibank designed a series of menus which defined their strategic external information needs. An outside firm was contracted out to scan, synthesize and digest the material and provide it in electronic format for the system. Figure 5 depicts the menu structure of the integration of their internal and external information.

9.5. Sample Database Design: The Integration of Internal and External Information

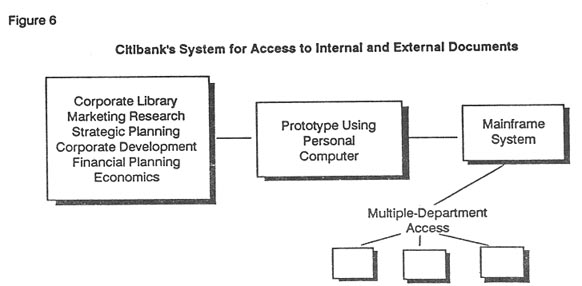

The Citibank intelligence databases were mounted on a corporate computer which utilized free-text search software with customized menu design. This system allowed multiple department

access to the system on a worldwide basis. A monthly

corporate newsletter was produced from the database for senior executives

on a worldwide basis. Figure 6 depicts Citibanks ability to ac-cess both

their internal and external documents on a fully integrated system.

10. SUMMARY

With the globalization of companies (acquisitions,

divestitures, and expansion into new market (e.g., Asia, Eastern Europe,

etc.) corporations have a pressing need to communicate inter-nally and

simultaneously integrate information from the external business environment.

Those corporations and organizations which develop shared information networks

early in the 90s will gain a significant competitive edge in their marketplace

during the next decade.