Donald E. Riggs

University Library

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

What is wrong with library technology, and what is right with this technology? Too often , these types of questions are answered by library staff. More emphasis has to be placed on meeting the expectations of the users of library technology (and particularly the end-users). Are the online public access catalogs designed for the user to easily access the various databases? If not so, how can they be improved? Are the help menus for users written plainly? Can the user move from one terminal to another one and find the same enhancements (e.g., help screens)? Are users having difficulties in using multimedia/hypermedia technology? If so, how can improvements be made?

This paper will attempt to provide methods (and examples) for answering the above concerns. It will also reveal models that can be employed while users are assessing library technology.

1. BRIEF HISTORY OF LIBRARY TECHNOLOGY

As early as the 1930s, punched-card equipment was used in library circulation and acqui-sitions. Shortly after this breakthrough, other library-related applications were made to library procedures. However, the movement was slow and the most practical data processing applica-tion could be found in library circulation. In 1945, Vannevar Bush displayed unusual vision by urging scientists no longer dedicated to the war effort to turn their creativity to making knowledge more accessible. The device he envisioned, which he called "memex," was a desk that incorporated a numerically-controlled microfilm store, reader, and camera. The stored information would include both published works and personal records; several items would be visible simultaneously at high resolution. He pointed the way for technological developments that have only recently emerged; displays that show several documents at once; personal machines for creating and organizing notes and papers; and hypertext for systems generating links between items of information. The 1960s brought time-sharing computers which enabled libraries in the United States to realize some value from cooperative ventures. The Library of Congress, in the mid-1960s, began using computers for producing machine-readable catalog records. In the early 1970s, some major breakthroughs occurred in library technology; OCLC began its cooperative cataloging project. UTLAS began a similar operation in Canada. A few years later, the Research Libraries Group (RLG) was formed. And regional networks (e.g., the Washington Library Network) were developed to serve a similar purpose. By the late 1970s, minicomputers were being used in libraries (e.g., the National Library of Medicine). Commercial systems for searching reference databases online also emerged (e.g., Bibliogra-phic Retrieval Services, BRS; DIALOG/Lockheed (Riggs, Donald E, 1990).

Technology is a tool which enables libraries to deliver service in a more efficient manner. In the history of library technology, several predictions have been and are being made about how technology will revolutionize libraries, and some prognosticators have even gone so far to predict that technology will lead to the demise of libraries. One prediction that few, if any, prophets denoted was the impact of the microcomputer on libraries.

2. THE ONLINE PUBLIC ACCESS CATALOG

The online public access catalog is a significant invention in the evolution of library technology. In addition to providing a substantial improvement to the access of the library's bibliographic records, it has allowed the user to access the library's records from remote locations. OPAC's have also provided the opportunity for users to access locally-produced and commercially-acquired databases. While the traditional card catalog allowed the users to have bibliographical access to about 60 percent of a library's total collection, the OPAC can provide the same type of access to nearly all of the collection(s). Via internet, users have access to other libraries' OPACs throughout the world.

3. EXPECTATIONS: MORE AND MORE

OPACs have brought forth greater expectations from the users. For example, since they now can see how technology can improve access, users are demanding that more databases (including full-text materials) be loaded into the online catalog. They do not understand why more full-text material is not available via the online facility. They also want to access all information via one terminal (not have to separately use an OCLC or a RLG terminal). And they are even beginning to ask about the possibility of having CD-ROM products/services included in the online catalog. In essence, the users are most grateful for the improvements library technology has brought forth; however, they cannot understand why technological advancements cannot be introduced more quickly. The exponential demand for more services via technology is encouraging. Technology is providing the opportunity to finally fulfill users' needs.

4. A USER-STUDY PROJECT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

The Library at the University of Michigan is the fifth largest academic library (collection wise) on the North American continent. It has a long-standing record for being rather innova-tive in defining and improving services offered for its users. In the Spring of 1991, the UM Library employed a private consulting firm to conduct a user satisfaction survey. In the 53-question telephone survey, users were asked to indicate their levels of satisfaction with a variety of Library features and services. A total of 351 individual surveys were completed, 159 for undergraduates, 128 for graduate students, and 64 for faculty members (45.3%, 36.5%, and 18.2% of the sample, respectively). Participants were chosen at random. Results do not factor in those persons who declined to be interviewed (7.4% of those called), reported that they did not use the Library at all (3.6%), or reported that they mainly used libraries not in the University Library system, such as the business or law libraries (3.1%).

The largest portion of the sample (47%) identified themselves as being affiliated with the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. Another 18% said they were affiliated with the Rackham School of Graduate Studies, 15% with the College of Engineering, 7% with the Medical School, and 13% with other schools or programs.

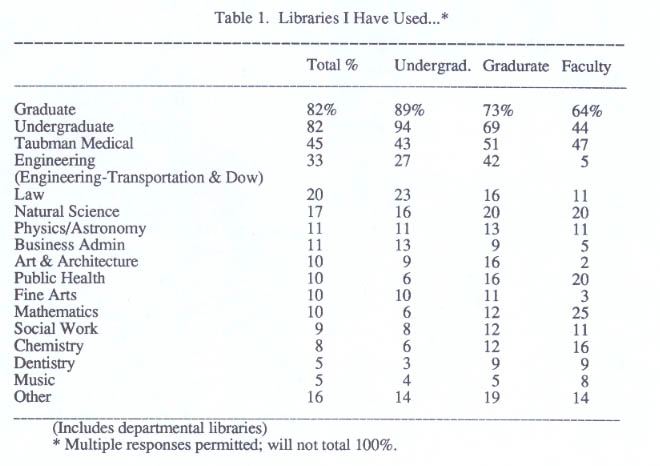

Although the survey was not intended for the purpose of gathering information about use of particular University Library sites, participants were asked to name all of the UM libraries that they had ever used and the one that they used most often. As Table 1 reflects, 82% had

used the Graduate Library at some time; the same percentage had used the Undergraduate

Library. The third-highest figure was 45%, the percentage who had used the Taubman Medical Library. (Though this survey does not include a qualitative assessment of use of particular sites--and no distinctions were made as to how individual Library units were used--the Library regularly gathers other statistics that provide some quantitative and qualitative indications of patterns of use.)

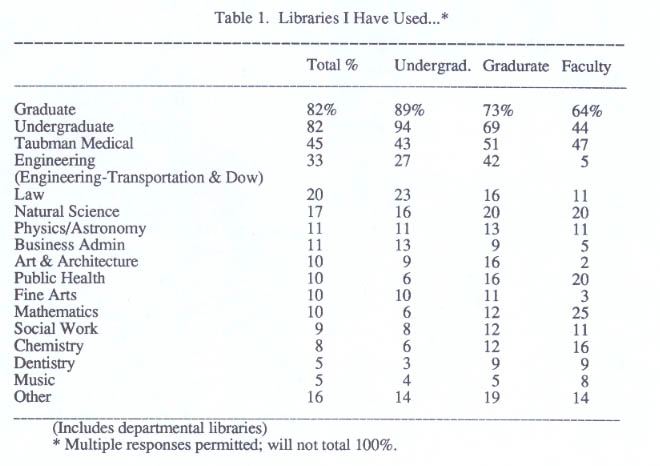

To the question of how satisfied participants were

with the University Library overall, for example, 87% of our users in the

sample said that they were "very satisfied" or "satisfied" (the two highest

categories). The average overall satisfaction score for this question was

4.0 on a scale of 1 to 5. Our distinct user-groups in the survey--undergraduates,

graduate students, and faculty members--were all very positive (88%, 85%,

and 86%, respectively). Only a handful of users (3%, 3%, and 5%, respectively)

were "dissatisfied" or "very dissatisfied" overall (Table 2).

In terms of frequency of use (often another indication of favorable attitudes), we found that 88% of our sample had used the Library or its services within the past two months (i.e., within the current semester), 60% having used the Library or its services "within the past week." Such high use was consistent among undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty members.

Information gathered from users clearly indicates that, to a large extent, the collections are still viewed as being the very essence of the Library. The University of Michigan has valued and strongly supported the acquisition of library materials since its inception, so it is gratifying to note that users show a high level of satisfaction with its collections.

The University of Michigan's online catalog is called MIRLYN (Michigan's Research Library Network). In the telephone survey, users were asked to indicate their levels of satis-faction with MIRLYN, WILS, PsycINFO, and two newer databases--the Meeman Archives of Environmental Information and the Public Affairs Information System (PAIS)--which were installed in January 1991. They were also asked to assess the availability of terminals in the libraries, training on MIRLYN and other databases, and their typical use of MIRLYN from inside and outside Library facilities.

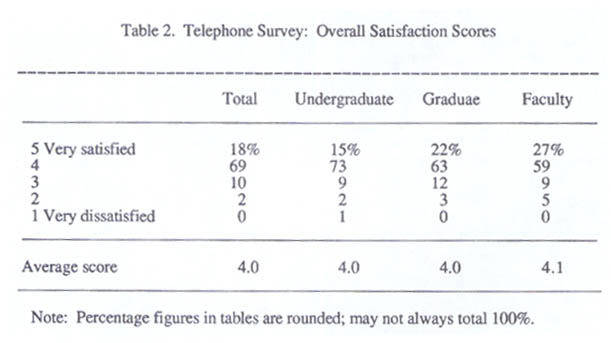

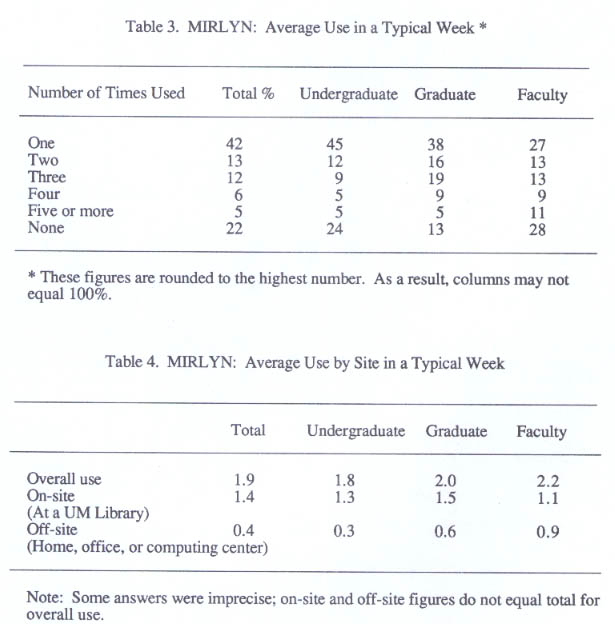

Over three-quarters (78%) of the Library's patrons use MIRLYN in a typical week, according to the telephone survey sample (Table 3). Average use across user-groups was indicated as being 1.9 times per week, with the low average of 1.8 being indicated for under-graduates and the high average of 2.2 being indicated for faculty (Table 4). Assumptions that were made originally that off-site use would become a major factor in how researchers would access the system were supported in the study, in part. Faculty members' use of MIRLYN is distributed nearly evenly between 1.1 times a week at a Library unit and 0.9 a week off-site. Undergraduates, on the other hand, use the database 1.3 times a week at libraries and only 0.4 times a week off-site.

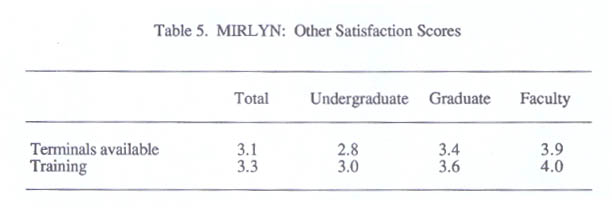

In two areas, data indicate a need for considerable improvement: The "availability of MIRLYN terminals in the libraries" and the "availability of training in the use of MIRLYN and other available databases."

The question of satisfaction with the availability of MIRLYN terminals produced one of the lowest overall scores (3.1 with 5.0 being the highest possible score) in our telephone sur-vey (Table 5). Undergraduates and patrons affiliated with the college of LS&A were least satisfied (2.8) with the number of terminals available. The level of satisfaction for graduate students in general (3.4) was somewhat higher than the overall score. It may be significant that respondents who said they mainly use the Graduate and Undergraduate libraries rated availa-bility of terminals at 3.0 on average, while persons who mainly use other facilities gave somewhat higher ratings. In light of the generally low ratings on this question overall, however, we believe that the Library needs to closely analyze patterns of use of MIRLYN terminals.

The subject of training in the use of MIRLYN also scored low (3.3 overall). Under-graduates were the least satisfied (3.0), while graduate students and faculty members were much more satisfied (3.6 and 4.0, respectively).

Responses to the open-ended question--"If you could add just one feature to the MIRLYN system to make it serve your needs better, what would that be?"--further illustrate the need for more training and assistance (which, by the way, 5% of our respondents asked for explicitly in this question). Indeed, in their responses themselves, users sometimes demons-trated basic misunderstandings of how MIRLYN can currently be used. For example, 3% of respondents said they would like to have MIRLYN indicate the current circulation status (checked out, due dates, etc.) or special locations of materials (e.g., University Reserve) --points of information which, in fact, MIRLYN already indicates. Other responses, such as "difficult to use system," "difficult to find titles," "more detailed instructions," and "self-help book next to terminals" all constitute clear calls for help and indicate a need for additional and/or different kinds of training.

Other responses indicate additional problems as perceived by users. Several relate to characteristics of the system that are based on the vendor's design and are therefore not within the Library's ability to change, but they are nonetheless revealing.

"Not enough space on screen; keep having to switch screens."

"Screening by subject rather difficult."

"Option of seeing an abstract."

"Improve Wilson index, very incomplete."

Ten percent of our respondents asked for a more "user-friendly" system. Many also asked for more information along the way as they conducted their searches. In other contexts, the Library has also received indications of the need for a "better user-interface" with MIRLYN, and through it to other systems. Responses in this study seem to validate those previous indicators and further merit the Library's careful attention and analysis. Work on a new user-interface might well address users' general desires for a less difficult system, while also contributing to our capacity to improve service in the area of training.

At any rate, given that more than half of our participants responded to the open-ended question by specifically asking for greater assistance or by offering suggestions that indicated difficulty in working with the current system, we believe that the Library should give attention to finding ways to help patrons use the system more productively--by augmenting MIRLYN where possible and appropriate and, certainly, by improving our training materials and procedures (The Library and Its Users, 1991).

5. USER-FRIENDLY INTERFACES

The study at the University of Michigan Library reinforces the belief that mechanisms permitting interactions between the human and the machine have much room for improvement. Intelligent front ends are evolving, but higher priority has to be placed on this important feature. Principles of artificial intelligence and expert systems have to be incorporated into the formulation of user-friendly interfaces. These principles will permit the design of interfaces that encourage users to interact with library technology. Frustrations resulting from the inabi-lity to interact intelligently with library computers result in a dampened enthusiasm on the part of users to use these tools. One can readily detect the effectiveness of library technology by examining the interface mechanisms.

While the application of expert systems to libraries remains in their infancy, information scientists are already considering the next advancement beyond expert systems. That next step includes an attempt to mimic the human brain. This endeavor is known as neural networking. Recent and future advances in neural networks will play a major role in developing the capabi-lities of expert systems. Creating artificial neurons (similar to those in the human brain) that are interconnected will permit the sharing of information and performing tasks simultaneously. This two-dimensional approach works best at recognizing patterns. Instead of looking for patterns, expert systems distill the decision-making process used by human experts into rules of thumb. It is predicted that a combination of expert systems and neural networks could find the answers to those problems too complex for either to solve alone.

There is much more research required before one can truly replicate the human brain. Nevertheless, a much better understanding is being grasped on how the brain functions. Combining the principles of neural networking with library expert systems will result in a powerful "intellectual" library tool. We will probably not see this combination occurring until around the latter part of the 1990s (Aluri & Riggs, 1990).

6. FOR WHOM IS LIBRARY TECHNOLOGY SELECTED?

This is a thoughtful question. Based on a critical evaluation of some of our library technology, one might conclude that it was selected for the library staff. The user needs are commonly pre-defined. When one scrutinizes Requests for Proposals (RFPs) for library technology, it is not abnormal to find that the RFPs' writer(s) have already decided what the user needs. How many RFPs are written jointly with library users? How many RFPs are written based on a user survey? How frequent do library managers/systems personnel engage in discussions with the user on the effectiveness of specific library technology? How can the passive attitude toward library users be changed? Many other pertinent questions could be posed about how the users' needs should be factored into the library technology decision-making process. The emphasis should be on thinking critically about how library technology can improve the users' skills in using the library's intellectual assets. It is evident that the majority of research on the relationship between users and library technology have occurred within academic libraries. Some libraries, e.g., school and public, have been "ignored" during research pursuits on library technology. Consequently, many OPACs have been installed in public libraries without much attention given to their users.

7. COMPETENCY SKILLS FOR TECHNOLOGY ENVIRONMENT

The competency skills (e.g., analytical and human relations) necessary for librarians and staff to work judiciously with the users will, to a large extent, determine how effective the inter action is between the human and machine. In referring to the skills needed by librarians in the automated environment, Stafford and Serban noted the following: 1.) User/staff interfacing skills, 2.) knowledge of traditional and automated reference sources, 3.) data retrieval skills, 4.) information technology skills, 5.) instructional skills, and 6.) organizational skills (Stafford & Serban, 1990). It is crucial for librarians to understand how databases are structured and maintained.

8. THEORIES OF LEARNING

A serious omission in library science curricula is a course or two in learning behaviors/ processes. Librarians are expected to work with diverse users; few librarians have had any instruction/ training in learning theory. It is especially important for librarians to have a grasp of the principles of cognitive learning. Obtaining a working knowledge of learning theories will pay many dividends.

9. CONCLUSION

As library machines become more intelligent in design and function, evaluation ratings from users will rise accordingly. Up to now, one could describe library technology as a collection of "dumb machines." Improved user interfaces are urgently needed. The architec-ture for online catalogs will have to undergo a metamorphosis. Part of this transformation will require a movement toward client servers. The local terminals can contain much information that is not carried on the mainframe.

The question on how best to evaluate library technology will remain with us. We are and will continue to witness a move from the quantitative aspects of library technology to the qua-litative features.

As we approach Toffler's New World Information Order, we will see more sophisticated use of library technology (Toffler, 1980) And the multi-dimensions of user behavior will be better understood.

Even though standards and established protocols are

necessary for maintaining consis-tency in library technology, a larger

challenge will be for us to achieve a more comprehensive understanding

on how humans learn. The "Perfect System" will probably never exist; how-ever,

we must continue to destabilize the status quo and seek out improvement

and change.

REFERENCES

Aluri, Rao and Donald E. Riggs. Expert Systems in Libraries. Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Press, 1990.

The Library and Its Users. A Report from the User-Study Project on Opinions, Attitudes, and Expectations of Patrons of the University of Michigan Library. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Library, September 1991.

Riggs, Donald E., "Introduction to Future Library Technology," in Libraries: A Vision for the 90s and Beyond. ed. by Edwin B. Burgess. Fort Monroe, Virginia: Library and Information Network Center, 1990.

Stafford, Cecilia D. and William M. Serban, "Core Competencies: Recruiting, Training, and Evaluating in the Automated Reference Environment," Journal of Library Administration 13 (1/2): 87, 1990.

Toffler, Alvin. The Third Wave. New York:

William Morrow and Company, 1980.