Figure 1. The Impact of Automation on the Skills Support Staff Used in the Library

Karen Horsfall

University of South Australia Library

Magill Campus

Magill, South Australia 5072

E-Mail: HORSFALLK@MAGILL.UNISA.EDU.AU

Abstract: The rapid implementation of information technology in all areas of life, including libraries, has led to concerns about how information technology transforms the nature and quality of work. What is the impact of information technology on workers? Library, office and industrial automation research has shown that the impact of technology depends on how and why it is used, rather than on the technology itself.

A case study undertaken at a campus library of a multi-campus tertiary institution, examined the impact of an integrated turnkey system on library staff. The study was particularly concerned with the affects of automation on the quality of working life, job satisfaction, client relations, self-esteem, morale, the pace of work and the control of organizational functions. Other aspects also considered were staff involvement in the implementation of the system, staff training and attitudes of staff towards the system.

This paper discusses the impact the automated system had on staff quality of working life, job satisfaction, client relations, self-esteem, and morale. Results showed that the system had a significantly greater impact on library support staff than on librarians.

Information technology (the convergence of computer technology and telecommunications) has pervaded our work and home lives in the last decade. One cannot do anything without it touching some aspect of our life - going shopping, telephoning interstate, doing the banking, or borrowing a book, etc. It has changed and continues to change the world our parents knew.

The rapid spread of information technology in our society is due to its ability to store, analyze, record and transmit information accurately, speedily and in large quantities. Therefore it is not surprising that organizations whose operations are information intensive, like libraries, have tried to incorporate information technology in their systems. Major world libraries have installed online public access catalogues (OPACs) since the late 1960s. The ability to search online databases half a world away has also been available to libraries since the mid-1970s; and during the 1980s libraries introduced microcomputers and compact disk technology.

However the development of fourth and fifth generation computers in the mid-1980s and the subsequent availability of better, more flexible and easier to use software, has meant that automation of nearly all aspects of library systems is now possible. Integrated turnkey automated library systems are now available at a reasonable cost for even the smallest library to implement.

The rapid implementation of information technology in all areas of life has led to concerns about how information technology transforms the nature and quality of work. What is the impact of infor-mation technology on workers? The organizational psychologist Shoshana Zuboff argues that infor-mation technology is characterized by a fundamental duality:

However, information technology also allows the employer

to automate the workplace by:

• using technology to replace human effort, skill, and knowledge to perform a process at lower cost• emphasizing the machine's intelligence

• placing controls over the access of the organization's knowledge base

• using the technology as a fail-safe mechanism to monitor and increase certainty and control over production and the organizational functions (Forester, 1989; Zuboff, 1985, 1988).

Most of the research available on the human impact

of automation deals with automation in the industrial or office environments.

A literature search reveals that only 3% of library studies inves-tigate

the effects of automated systems on staff. The rest focuses on the effects

of automation upon organizational structure; ergonomic issues; health and

safety issues; the management and implemen-tation of automated systems;

and equipment problems.

2. THE IMPACT OF AUTOMAITON

Studies of office, industrial, and library automation report that automation has the greatest impact on staff in the lower levels of the organization where the work is routine; and less impact at the top where authority and decision making are concentrated (Kraske, 1978; Zuboff, 1982, 1985, 1988; Shiff, 1983; Atkinson, 1984; Diebold, 1984; Freedman, 1984; Roscow, 1984; Dakshinamurti, 1985; Waters, 1985, 1986, 1988, 1989; Caudle & Newcome, 1986; Lynch & Verdin, 1986; Horny, 1987; Bergen, 1988; DeKlerk & Euster, 1989; Jones, 1989; Forester,1989; Harris et al, 1989; Hoer et al, 1989; Long, 1989; Olsgaard, 1989; Smith, 1989; Prentice, 1990).

The literature suggests that the positive effects

of automation are:

• a reduction in repetitive work and tedious procedures• an increase in skill level

• possibly higher job satisfaction

• an increase in the variety of tasks

• greater flexibility

At its worse, the impact of automation on employees,

especially lower level employees, can result in:

• the degradation of the quality of working life;• the decline in interpersonal communication and client relations;

• an increase of employee stress, depersonalization, and boredom;

• lower job-satisfaction;

• the loss of control over the pace of one's work and organizational functions;

• lower self-esteem and staff morale.

However, the research does not indicate whether

the introduction of information technology will have either a positive

or negative impact on employees in an organization. Instead the research

shows that the impact of technology depends on the how and why it is used,

rather than on the technology itself.

3. A CASE STUDY

Faced with a dearth of library research in this area, a case study was devised to investigate the effects of automation on library employees. The case study was carried out at a campus library of a multi-campus tertiary institution over the course of 16 months (from May 1990-August 1991), when the library implemented an integrated turnkey automated system. The system replaced the library's manual systems - catalogue, circulation, holds, and reserve loans - thereby dramatically changing the work of some of the library staff.

The study particularly concentrated on how an integrated, automated library system affected quality of working life, job satisfaction, client relations, self-esteem, morale, the pace of work and the control of organizational functions. Other aspects also considered were staff involvement in the implementation of the system, staff training and attitudes of staff towards the system. However, due to the limitations of time and place this paper discusses the impact the automated system had on the quality of working life, job satisfaction, client relations, self-esteem, and morale.

In order to study the impact of the new system on

staff, employees were interviewed and asked to answer a questionnaire.

Both procedures were carried out three times during the study:

• once prior to automation;The questionnaire consisted of a validated job satisfaction measure - the Job Descriptive Index (JDI), and questions that gave an indication of the changes in staff self-esteem, morale, and quality of working life.• again five months after the system was implemented; and

• once more nine months after the system was implemented.

This resulted in some quantitative data which was analyzed using non-parametric tests, and a wealth of qualitative data that was analyzed in depth.

4. THE QUALITY OF WORKING LIFE

Automation has often been accused of affecting the quality of working life because it effectively allows for the deskilling of work. That is it allows tasks to be broken down to their most basic level or replaced by the machine altogether, so that staff need little initiative or skills to carry them out. Furthermore the job becomes very narrow, with very little variety, autonomy, creativity, etc. There-fore, it was important to find out whether staff jobs were deskilled in the automation process. Qua-lity of working life was measured by asking staff about changes in skill and task levels in their jobs.

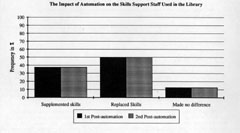

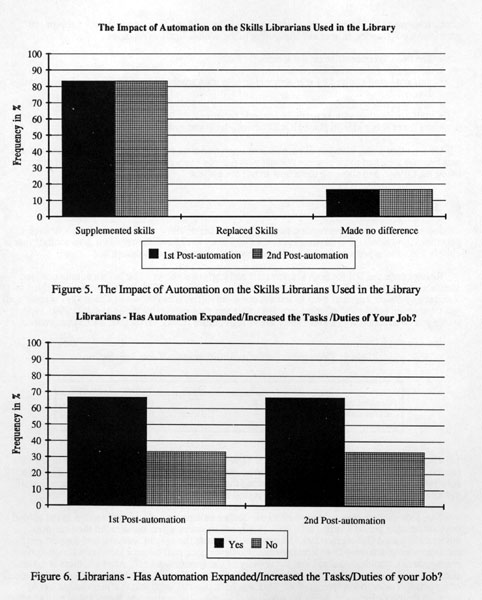

The majority of support staff either believed that

they acquired new skills from automation to supplement their other skills;

or that the system had replaced their skills in the library (See Figure

1). Support staff reported that acquired skills were limited to the areas

of computing and computers.

Figure 1. The Impact of Automation on the Skills Support Staff Used in the Library

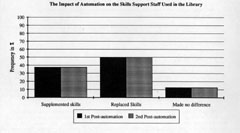

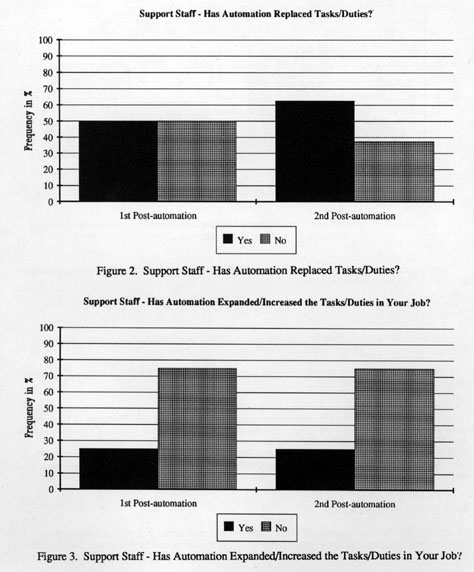

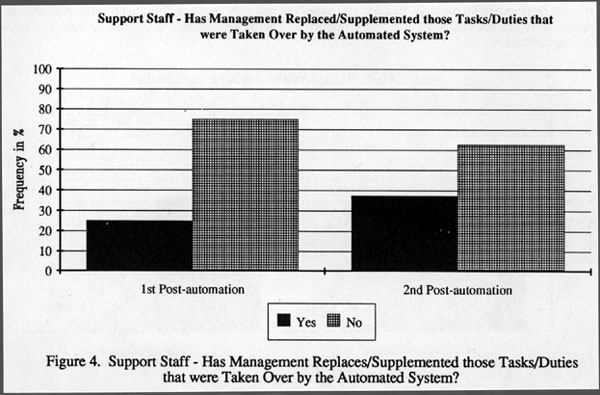

Figure 2 shows that automation has also replaced some of support staff's tasks/duties. Support staff reported a majority of very tedious and repetitive tasks/duties were lost to automation, and that they were glad to lose these duties. However, the automated system did not increase the number or variety of tasks; nor were new tasks or duties allocated (except for more shelving) to the majority of support staff to supplant the ones that had been eliminated, as shown in Figures 3 & 4. This resulted in support staff reporting that their jobs had become even more routine with less variety, interest, or challenge than they contained before automation. In other words, support staff's work was generally deskilled during the automation process as acquired skills and tasks did not make up for the loss of other skills, tasks or duties.

The lack of variety in most support staff's work also affected the performance of their work. Mistakes, particularly at check-in, were made because the assistants found it difficult to concentrate on the screen all the time. It was suggested that these mistakes were due to the support staff's work

becoming more abstract with the automation. Zuboff

(1988) suggests that employees have great difficulty concentrating on tasks

that are not only conceptually abstract, but also routine and unchal-lenging

- just like the checkout and check-in duties. Therefore mistakes occur

due to boredom and poor concentration.

Figure 4. Support Staff - Has Management Replaces/Supplemented those Tasks/Duties

that were Taken Over by the Automated System?

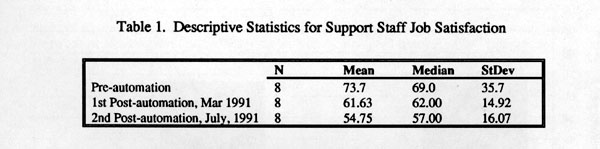

The impact of the automated system on the librarians was completely the opposite to that of the support staff. The librarians reported:

• that they had acquired new skills from automation which supplemented their skills in the library (Figure 5); and

• that automation had replaced a number of tedious and repetitious tasks and increased the variety, challenge and interest in their work (Figure 6).

These results follow the pattern of the effect of automation on the quality of working life found in the literature.

The real question is why is the impact of automation on the quality of working life so different for the two types of employees? I believe that when one closely examines the nature of librarians'

work one realizes that their work is not really involved in the automated system. Of course they use

the OPAC, but the functions of their work have not been automated. Most of their work is non-

routine, indeterminate and requires discretion. These

aspects of work cannot be automated. On the other hand, most of the functions

of the support staff's work, especially the library assistants, can and

have been automated. Therefore the impact is greater.

5. CLIENT RELATIONS

A great fear for most library staff when implementing an automated system is the decline in interpersonal and client relations (Bergen, 1988). Support staff particularly fear that client relations will suffer because of the system picking up more infringements, making them seem stricter.

Support staff reported that staff-client relations had declined, but not because of the system picking up more infringements. Instead the system has made it easier to deal with patron infringe-ments, not more difficult. This was because the computer took the blame for these things, not the staff. It seemed that support staff-client relations have declined for other reasons. Support staff identified the following factors as contributing to the decline in client relations:

• The need to concentrate on the screen,

• the height of the circulation desk,

• staff not being allowed by management to help with anything more than general directional queries,

• lack of privilege level,

• staff not dealing with as many borrowers' enquires,

• the users being able to place HOLDS themselves, and system breakdowns.

On the other hand, librarian-client relations improved

after automation. Most librarians felt this was because they had more positive

contact with patrons - successfully helping them find materials using the

OPAC, and showing them how to use the system.

6. JOB SATISFACTION

Job satisfaction is the perception that one's job fulfils or allows fulfillment of one's desires, ex-pectations, and needs. Job satisfaction studies of library staff have shown that it is an attitude that is closely linked to aspects of the job itself and therefore the quality of working life.

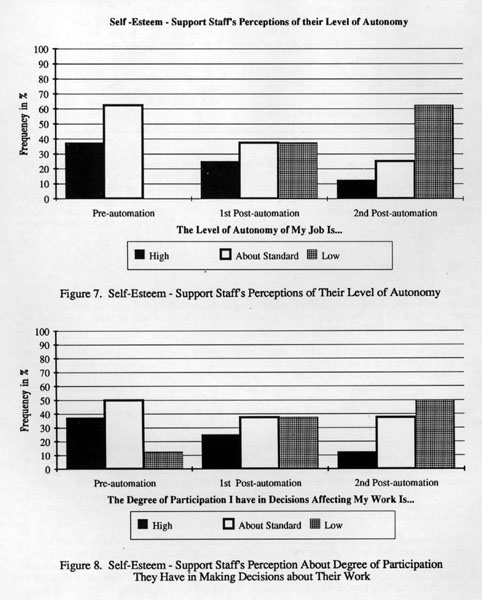

Results from the JDI for both support staff and librarians

showed that before automation, job satisfaction was balanced, that is neither

positive nor negative. A Friedman Two-way Analysis of Variance by Ranks

Test was used to test the observed differences (shown in Table 1) in

support staff job satisfaction before and after automation. This test showed

that by the end of July 1991 support staff's job satisfaction was significantly

lower than before (c2=6.75, p=.038, a=.05) automation.

Further, using a Wilcoxen Matched-Pairs Signed-Rank Test a significant difference in job satis-faction was obtained between pre-automation scores and the second post-automation period (April-July 1991) scores (T=4, a=.05). This supported the view that there was a decline in support staff job satisfaction some time in the 6-9 month period after automation.

Two factors were seen to contribute to the decline in support staff job satisfaction in the second post-automation period (April-July 1991). First, a Hawthorne effect occurred in the first post-automation period (November 1990-March 1991) because the system was new and support staff received a lot of attention from management. However once staff became familiar with the system, management's attention declined and the novelty of the system wore off. After all, there is nothing stimulating in running a light pen over bar-codes. Second, support staff had very high expectations of automation prior to implementation. This was because staff were told that automation would solve all their problems and their jobs would be different. The reality was that nothing really chang-ed. Their jobs were nearly the same as before automation, but with even less variety and challenge. The non-realization of such high expectations led to disappointment, anger and frustration, which affected job-satisfaction.

A Friedman Two-way Analysis of Variance by Ranks Test was also used to test the observed differences (shown in Table 2) in librarian job satisfaction before and after automation. This test showed that by the end of July 1991 there was no significant difference in job satisfaction after automation (c2=3, p=.285, a=.05).

Although librarians experienced no significant difference

in job satisfaction, Table 2 shows that the librarians experienced an increase

in job satisfaction during the first post-automation period (November 1990-March

1991), which fell during the second automation period (April-July 1991).

Interviews with the librarians indicated that this was due to the fact

that the system being new and interesting in the first post-automation

period (November 1990-March 1991), and awareness of the system's limitations

as the they became more experienced with it during the second post-automation

period (April-July 1991).

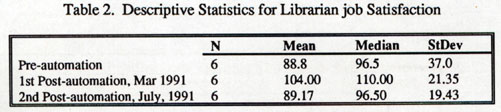

7. SELF-ESTEEM

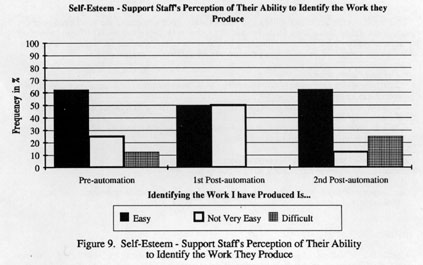

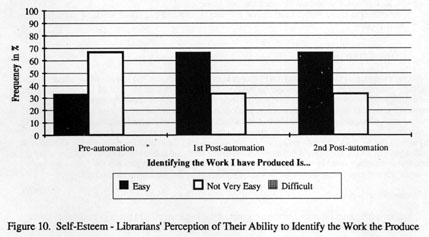

Self-esteem is the favorable opinion or approval of one's self that leads to feelings of self-confidence, worth, strength, capability, and of being useful, valuable, and necessary to the organi-zation. Self-esteem was measured by asking staff how they felt about their position in the organi-zation and the work they performed.

All library staff enjoyed a good level of self esteem before automation. That is, they felt that their jobs were important, and worthwhile, and that they had some degree of autonomy and control over their work. However by the end of July 1991, self-esteem for support staff was lower than before automation, although librarians' self-esteem remained high. Analysis of the questionnaire and the interviews indicated that the negative impact on support staff self-esteem was due to the decline in support staff's quality of working life, job satisfaction, and the loss of responsibility and control over their work.

One can see in Figures 7 and 8 the gradual change in support staff's autonomy and control over their work. Before automation most support staff believed that the autonomy and control they had over their work was about standard, that is about the same for all of them. However, this gradually changed so that by the end of the second post-automation period (April-July 1991) most support staff felt that they had less autonomy and control over their work. Analysis of support staff inter-views suggested that this gradual change reflected management's decisions about control over the systems functions.

Self-esteem also offered an insight into the way automation can affect the ability of staff to identi-fy the products of their work. Figure 9 shows that support staff had some difficulty in identifying their output in the first automation period (November 1990-March 1991). This change was due to the physical end-products of their work disappearing (no cards to file, etc.). Support staff were used to producing something concrete from their work. Switching to work that didn't seem to produce anything initially caused them to have difficulty in identifying the products of their work. However, by the second post-automation period (April-July 1991) they could more readily identify their output as they had adjusted to the system.

Unlike the support staff, the librarians found it easier to identify their output after automation than before it, as shown in Figure 10. This is due to the nature of most librarian work. Helping academic staff and students find material, conducting user education classes, sitting at the informa-tion desk answering questions, etc. does not generally produce any visible signs of work. Although other parts of their work like indexing or ordering material, do provide more concrete outcomes.

This change in the librarians' ability to identify their output was due to the functionality of the system. How the system allows the librarians to see the work they produce is difficult to explain, as they themselves have difficulty in explaining it. However in Information Services, the librarians know they are successful in teaching patrons to use the catalogue because of:

• The daily loans figures,

• Satisfying more user enquires by using the OPAC which shows if material is available and where it is available,

• Helping lecturers plan their units by being able to tell them which books are being used on Reserve and how often,

• Able to get accurate bibliographies of current material on a subject printed out for a lecturer and their students (Librarians, April-November 1991).

Zuboff (1988) suggests that this type of occurrence is not unusual after an organization has automated, as information technology has the power to

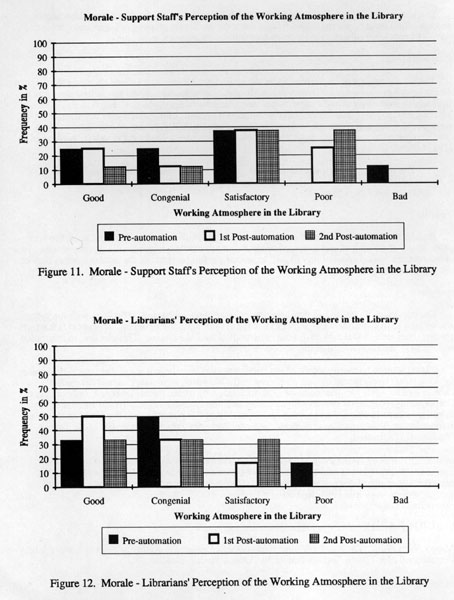

Morale is a pervading sense of cheerfulness, confidence, excitement, etc. within the work envi-ronment. Staff morale seems to be a function of management policy, the quality of working life and job satisfaction. Therefore it will clearly vary in different work situations. Morale was measured by asking staff about perceived changes in the working environment. Figures 11 and 12 show that before automation most staff felt that morale was satisfactory to good. However after automation, most support staff felt that morale had declined, whisecond the librarians were unanimous that there had been no change to morale, or that it had increased. The interviews indicated that these conflict-ing results could be due to:

• A lack of communication between the two groups; and/or

• the different effect automation had on job satisfaction and quality of working life within the two groups.

9. CONCLUSION

The evidence of the case study and other research suggests that the impact of information tech-nology on employees will not always be positive. However, if a major goal of library management is to maximize resources to effectively serve their users and one of those resources is human resources, then an automated system that predominantly impacts negatively on staff is a waste of resources - of expertise, ideas, skills and knowledge; a waste of human potential. Therefore it is important for management not just to automate the library (that is, the operational aspects of their systems) but to work towards integrating the system into the working environment to benefit both

management and employees. I believe that to realize this goal those involved in implementing infor-mation technology need to incorporate as part of the implementation process the following basic human impact principles, which are based on participative management techniques.

Communication

Staff must be kept informed of the progress of the implementation process in order to avoid feelings of alienation and powerlessness over the change process.

Participation

In addition to being informed, staff must be able to actively participate in the implementation process. Staff need opportunities to discuss the implementation process, ask questions, raise con-cerns and provide feedback to those implementing the information technology.

Consultation

The whole concept of implementing an automated system revolves around changing the ways in which tasks have been done. To maintain staff quality of working life and job satisfaction, it is not sufficient to superimpose one system on another; due attention must be paid to job design (Dyer and Morris 1990, p. 185). Management in consultation with staff, must design jobs that contain all or some of the following elements: variety, autonomy, responsibility, feedback and recognition, social contact, discretion and control, achievement, and opportunities to learn and develop. As Austen (1987) stated,

the person to the system, rather than to humanize the system - but it is courting trouble!" (Austen 1987, p. 136).

Besides the initial training staff receive in the use of the system, they also need access to appro-priate levels of training as and when required. Failure to provide ongoing training may result in lack of interest, frustration and inability of staff to realize the full potential of the system to meet their or the users' needs.

Support

The provision of quality and timely support to staff who are having difficulties with the system, allows staff to feel confident that they can use the system to its full potential. If support is not forth-coming, staff tend to feel they have little or no control over the system. This can lead to frustration and stress as staff doubt their ability to cope with the system.

It is difficult to be more specific as not enough studies have been done in this area to determine the long term effects of automation on library staff. However, technology cannot determine what choices will be made for what purpose (Zuboff 1985, p.6) within the organization, only people can. Consequently, only when system administrators and library managers implement automated systems to utilize both technological and human resources to their full potential, will the negative effects of automation on library staff be minimized. As one worker in Zuboff's In the Age of the Smart Machine (1988) mused,

Abbott, W. (1988). The impact of information technology on the quality of work in library jobs. Unpublished MA Thesis, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia.

Atkinson, H. C. (1984). "The impact of new technology on library organization," In The 29th Bowker Annual of Library and Book Trade Information . New York: Bowker. pp. 109-114.

Atkinson, H. C. (October 15, 1984). "Who will run and use libraries? How?" Library Journal, pp. 1905-1907.

Austen, G. (September 1987). "What about the bosses?" Cataloguing Australia, 13 (3):131-137.

Bergen, C. (1988). "Instruments to plague us? - Human factors in the management of library auto-mation," Library Management, 9 (6): 3-55.

Caudle, S. L. & Newcomer, K. E. (1986). "Managing electronic patterns: the office of the future," Information Management Review, 2 (2): 17-24.

Dakshinamurti, G. (December 1985). "Automation's effect on library personnel," Canadian Library Journal, pp. 343-351.

DeKlerk, A. & Euster, J. R. (Spring 1989). "Technology and organization metamorphoses," Li-brary Trends, 37 (4): 457-468.

Diebold, J. (November 1984). "How new technologies are making the automated office more human," Management Review, 73: 9-17.

Dyer, H. & Morris, A. (1990). Human aspects of library automation. Aldershot, England: Gower.

Forester, T. (1980). The microelectronics revolution. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Forester, T. (1985). The information technology revolution. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Forester, T. (1987). High-tech society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Forester, T. (April 18, 1989). "Automation: for better or worse?" The Australian, pp. 44-45.

Forester, T. (1989). Computers in the human context. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Freedman, M. J. (June 15, 1984). "Automation and the future of technical services," Library Journal, pp. 1197-1203.

Harris, C. L. (1989). "Office automation: making it pay off," In Computers in the human contex, edited by T. Forester. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 367-376.

Horny, K. L. (October 1, 1985). "Managing change: technology and the profession," Library Journal, 110: 56-58.

Jones, D. E. (Spring 1989). "Library support staff and technology: perceptions and opinions," Library Trends, 37 (4): 32-56.

Kraske, G. (1979). The impact of automation on the staff and organization of a medium-sized academic library: A case study. Indiana: Indiana University.

Long, R. J. (1989). "Human issues in new office technology," In Computers in the human contex, edited by T. Forester. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 327-334.

Lynch, B. P. & Verdin, J. (10 December 1986). Relationship of technology and characteristics of library functional units. (CLR-799A). Washington D.C.: Council of Library Resources.

Olsgaard, J. N. (Spring 1989). "The physiological and managerial impact of automation on libra-ries," Library Trends, 37 (4): 484-494.

Prentice, A. E. (1990). "Jobs and changes in the technological age," Journal of Library Adminis-tration, 13 (1/2): 47-57.

Roscow, J. M. (September 1984). "People vs high tech: Adapting new technologies to the work-place," Management Review, 73: 25-28.

Shiff, R. A. (May 1983). "Office automation the human equation," Journal of Micrographics, 16: 28-31.

Smith, S. (1989). "Technology in banks: Taylorization or human-centered systems?" In Computers in the human contex, edited by T. Forester. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp.377-390.

Waters, D. H. (1985). University library administration, with special reference to new technology: A Tasmanian Case Study. Unpublished masters thesis, University of Tasmania, Tasmania, Austra-lia.

Waters, D. H. (July/August 1986). "Assessing the impacts of new technology on library employees," LASIE, 17 (1): 20-27.

Waters, D. H. (January/February 1988). "New technology & job satisfaction in university libraries," LASIE, 18 (3): 103-108.

Waters, D. H. (July/August 1989). "The effect of new technology on prestige, self-esteem and social relationships of university library employees," LASIE, 20 (1): 16-22.

Zuboff, S. (September-October 1982). "New worlds of computer-mediated work," Harvard Business Review, pp. 142-153.

Zuboff, S. (Autumn 1985). "Automate/Informate: the two faces of intelligent technology," Organi-zational Dynamics, 14 (2: 5-18.

Zuboff, S. (1988). In the age of the smart machine: The future of work and power. Oxford, Heinemann Professional.