OVERCOMING TECHNOPHOBIA THROUGH EDUCA-TIONAL PROGRAMS

OF INFORMATION STUDIES

Robert D. Stueart

Graduate School of Library & Information Science

Simmons College

Boston, MA 02115-5898 U.S.A.

Yupin Techamanee

Department of Library & Information Science

Khon Kaen University

Khon Kaen, 40002 Thailand

Keywords: Interdisciplinary Study, Information

Access, Technological Literacy, Curriculum Innovation, Information Management,

Education, Library Education, Library Science, Information Science.

Abstract: Technological developments and innovations

have facilitated changes in curicular offerings and emphasis in faculty

teaching expertise. Schools of information studies now must have, as a

preliminary focus, technological literacy. But the primary focus is upon

access, an approach which requires more interdisciplinary study and research.

Converging fields of computer science, communications theory, information

systems, artificial intelligence and operations research, among others,

with those of library and information studies prepare information professionals

to become technologically literate as they enter the workforce.

1. INTRODUCTION

Marshall McLuhan, as early as the 1950's, with his

"the medium is the message" sermon, alerted the world to the shift from

a print-oriented to a machine oriented audio-visual culture, which in a

short intervening time has become a full-blown electronic culture. This

new wave has brought with it greater reliance on the expertise of information

professionals whose responsibility is to guide society through a complex

ever changing information maze. What type of educational program best prepares

those who serve as intermediaries and guides, and specifically those information

profes-sionals who are working in such a changing information ladened environment,

is a vital question to address.

One constantly hears reference to "the" information

profession or information professional, with little concerted thought being

given to the meaning of those terms, which are all too frequently inappropriately

used because they are so broad, covering so many categories of professionals

in so many experiences, that they might be considered meaningless. By definition,

"information profes-sional" has become an umbrella term, used to describe

an array of individuals trained to handle information and the technology

to process and deliver it. Most importantly, that professional, as compared

to a technician, possesses knowledge in the discipline of information services,

with a set of guiding principles and a liberal education to enable an understanding

of the dynamics of society and culture. The information professional is

required to think conceptually and reason logically. This distinction is

being emphasized here in the beginning, because it is a vital point which

will be expounded upon later.

2. INFORMATION PROFESSIONALS

When one considers the potential of a total educational

market, there is no doubt that the human resources market for information

professionals is increasing. However, schools of library and information

studies are not alone in establishing a role in the "information society,"

nor are they the only ones preparing information professionals. Many professional

groups are wrestling with the problem of defining the information professional

marketplace, and in identifying the education of various professionals

in that continuum. Several ways of defining what information work have

emerged from those discussions, including it being defined by the: 1).

context or employing insti-tutions; 2) function or activities performed;

3) occupational title; 4) terms of the professional skills and competencies

required; and/or 5) placements patterns exhibited by the graduates of library,

information science, information studies and/or information management

programs.

When one closely examines the changing curicula foci

of programs of library and information studies, it is obvious that the

goals of those programs and the curicula which support them are changing

to address and encompass the needs of a much wider market. Library service

is one, albeit important, part of a host of retrieval based information

services which have their grounding in what can now be labelled interdisciplinary

curicula in schools of library and information studies.

In trying to encompass information systems, policies,

and resource management, information studies has become the more acceptable

term. Even the new Standards for Accreditation, developed by the

American Library Association with input from other professional associations,

including the American Society for Information Science, use the term "library

and information studies." (American Library Association, 1992) This definition

is important since it determines how schools address information studies

in their curicula (Sineath, 1992). The concept is a restatement of what

we librarians and information managers have always studied, but new techniques,

new technologies, and new thrusts have provided a new dimension for learning

and doing. The traditional library market is still the core of what is

being taught in schools of library and information studies, but wider market

options are attracting many graduates who are finding positions with such

titles as: on-line search specialist, abstractor, systems analyst, systems

designer, production designer and editor, technical writer, programmer,

media information specialist, market researcher, information specialist,

archivist, computer programmer, marketing information specialist, records

manager, and database development consultant, to mention just a few.

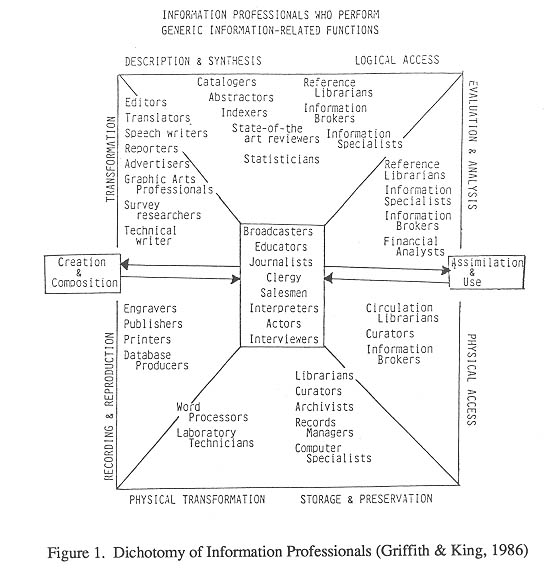

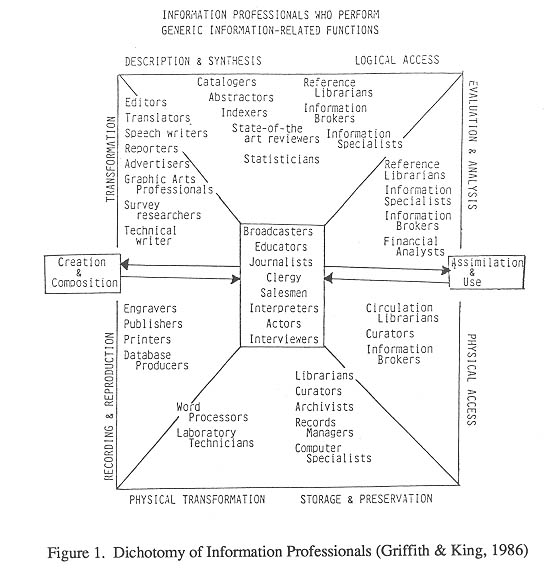

It is useful to examine one chart (Figure 1) from

a relatively recent study which delineates the various information professions,

and provides some parameters to the discussion of education for those information

professionals, who have been grouped, by researchers, into nine basic groups:

1. managing programs, services, and databases.

2. preparing data and information for use by others;

3. analyzing data and information on behalf of others;

4. searching for data and information on behalf of

others;

5. information systems analysis;

6. information systems design;

7. information research and development;

8. educating and training information workers; and

9. remaining operational information functions (Debons,

et. al., 1987).

3. SCHOOLS OF INFORMATION STUDIES

In such a diverse, dynamic, changing environment

it is almost impossible to construct curicula in schools of library and

information

studies to meet the needs of everyone preparing to enter the infor-mation

professions. Not only is it difficult, but it is also not even desirable

or necessary. The pri-mary focus in schools of library and information

studies, then, needs to be on constructing programs which are relevant,

timely, and meet the educational needs of a specific, identified segment

of the information profession's market. It requires identifying that particular

"nitch" which schools should target in preparing professionals for the

accelerating changes taking place in the external and internal environments

of organizations called libraries and other information centers.

A logical question then becomes whether it is possible

to modify, adapt, or further revise existing programs to address that changing

market, or if it would be better to just start over, or, alternatively,

forge stronger alliances with logical cognate disciplines to provide, more

focused and relevant infor-mation based programs. In many ways, we are

our own worst critics, believing it is not possible to adjust, or being

reluctant to commit to loosing an autonomy which has always been treasured.

Some information professionals already believe that other academic programs,

including those for compu-ter scientists and management information system

experts in schools of business administration and management, and those

for artificial intelligence workers and expert systems personnel in knowledge

engineering programs, are already better attuned to marketing needs and

therefore are meeting needs which schools of library and information science

seem to have, at worst, ignored or, at best, neglected.

In that educational process, "management schools

are educating people in information literacy and the role that information

plays in the modern organization; communication schools are preparing people

in information utilities; and computer scientists are ready to capture

the market for knowledge workers in how to prepare expert systems which

can answer people's questions. With such richness of activities, one might

ask if anything is left. The answer is the most important concept of all,

the service orientation.

Schools of library and information studies have the

educational advantage because they are pro-viding a broader understanding

of the information environment, and have historically been best at information

management. The orientation has traditionally been, and remains, toward

service. But those schools do not have the tactical advantage, and therein

lies part of the current problem. One fact is obvious in this complex technological

environment, a passive educational role no longer serves information services

well and things can no longer be done the way they were done or even marketed

a few short years ago. There are many more players with vested interests

in the new information marketplace, and that factor influences the recruitment

and education of many informa-tion professionals. Schools must be more

articulate and assertive in spreading the word on who is being educated

and how those graduates are then prepared to perform.

Sharper focused objectives for library and information

service education are demanded now, more than ever before, and in fact

are necessary for the survival of current programs as viable educational

entities. During the last decade there has been some initial, tentative

shifts in focus to accommodate that need. For instance, just ten years

ago fifty three percent of the then accredited graduate programs in North

America contained "information" in their title, now over 88 percent have

the term in their names. In most cases these are more than just cosmetic

changes. An examination of the statements of goals and objectives and curricular

changes indicate that schools are attempting to meet the needs of a greater

range of markets, employers, and operational contexts for information professionals.

A similar development and focus is now taking place in Thailand as professional

programs move to the graduate level, and as more information theory is

introduced with those curicula.

If schools of library and information studies are

to continue to attract persons interested in that specific segment of the

information profession, then the focus must be on preparing individuals

interested in developing information systems, with an added commitment

to providing access to the information needed. The access orientation is

paramount, because, no matter how impressive new technologies are; or their

rate of acceptance; or their eventual impact on society, the charge to

infor-mational intermediaries will continue to be one of providing the

right information, to the right person, at the right time, and in the right

format. Access is the key, and even though unrestricted access is still

in the future, it does raise many important educational issues relating

to the elements of: legal access, physical access, affordable access, intellectual

access, and organized access. Those economic and ethical considerations

are topics of concentration in educational programs of information studies

and must be further addressed in a systematic fashion before that day arrives.

Several schools in North America have developed reputations

for concentrating on a series of specializations in their curicula, while

leaving the generalist approach to others. Still other schools, with an

appropriate critical mass of faculty and an array of specialized courses

ranging from archives, and records management to expert systems and desk-top

publishing, remain generalist oriented by identifying "core" courses and

then guiding students into a number of different career paths, depending

upon the students professional goals, and in recent times, with a consideration

of the marketplace.

Another issue relates to whether schools are actually

educating information professionals or simply training information workers.

One writer recently observed: "we even hear of 'fifth genera-tion computers'

that will be able to see, hear, talk, recognize human faces, learn from

mistakes, and think; in short, that we shall soon be sharing the planet

with intelligence equal to, if not greater than, our own. One of the deeper

effects of this technological change has been to make us think about the

differences between training and education... Education, in the sense of

inculcating an appreciation of the use and limitations of information technology,

is not (training). Education connotes some-thing of value; something permanent;

a framework of readiness that can adapt yet still retain its identity (McGarry,

1988).

Some of what occurs under the guise of education

is actually training, but that is not necessarily all bad. However, the

point to remember is that a conceptual understanding is the foremost consi-deration

for education, not those skills and techniques which easily become obsolete

and which can, and perhaps should be best, learned on-the-job. But there

is a place for both education and a small amount of training in the curriculum.

In fact, some training is necessary, as long as it is placed within the

proper educational perspective. For instance, learning to conduct database

searches is a training technique which is tied to the more philosophical

issue of "what" and "why." With the continuing development of technology,

it is likely that additional training, perhaps in prerequisite non-credit

technology modules within academic programs, will become more prevalent.

For instance, Simmons has recently introduced a technology

skills competency non-credit module which must be taken by all students

before they matriculate in their first course, with the thought this prepares

all students to enter their first class with a common base, and some confidence

and competence in negotiating technological problems which they would be

expected to address throughout their academic program. The week-long workshop

includes demonstration of skills in text processing, using spreadsheets,

electronic mail, database management, etc. This is supported by the Technology

Laboratory within the school which is equipped with a wide range of technolo-gical

hardware and software, where the documentation is fully accessible and

where teaching assistants are available to work with individual students.

This intense, primary emphasis on technological competence then allows

for developing a more integrated and, indeed, pervasive intellectual discussion

of information theory and technology throughout the curriculum.

Schools which are best able to meet those challenges

are those with interdisciplinary programs and faculty expertise and often

with cross-curricular offerings which take advantage of the richness of

courses on information needs and access as reflected in the curicula of

the core program and cognate fields in educational institutions. Specific

cognate examples can be cited: "from law, such topics as intellectual

property, copyright, the effects of regulation of information flow within

and across national borders; from economics, methods for assessing

values and costs of information, links between information and productivity,

the economics of the information industry; from sociology, the influence

of information technology on social structures and processes and the characteristics

of 'information societies' need to be understood; from public administration,

matters of the effect of national information practices on third-world

development." (Haas. 1988). The list could go on.

There remains the difficulty of balancing educational

responsibilities between promoting the social mission of good and free

based services to clients who need information with, on the other hand,

the recognition that technology has been absorbed into work habits and

that it may not always be possible to provide everything to everyone at

no cost. The issue of information rich and information poor, in that dichotomy,

is an important educational issue.

4. CURICULAR DEVELOPMENTS

The curriculum "is the major academic device educators

have for confronting society's challenge." (Asheim, 1977) The curriculum

provides for the study of theory, principles, practice and values necessary

for the provision of information services in all types of agencies and

organi-zations. Content areas of the curriculum can be thought of in three

broad categories: knowledge, skills and tools. The knowledge areas relate

to philosophy, i.e., the foundations of information in society, environmental

and contextual knowledge, and management knowledge; the three areas of

skills requirements relate to communication, interpersonal and technological

skills i.e., program-ming, online searching, database management skills;

and the tools required are both quantitative and analytical, e.g., systems

analysis, research methods, descriptive statistics, logic, and bibliographic

or organizational, i.e., bibliographic control, abstracting and indexing,

data structures, and collection development (Daniels, 1987).

The role of information science in the curicula of

schools has gone through major revisions in recent years. One of the current

pressing issues relates to emphasizing that "information" is not synonymous

with information technology. The technology component, however, has received

a great amount of recent curicula attention and can be said to characterize

curriculum revision during the last decade. When one steps back from the

technology and views the philosophy imbeded in the information science

concept, the definition that is important to curricular development in

schools of library and information studies is that it is "the science that

investigates the properties and behavior of information, the forces governing

the flow of information, and the means of processing information for optimum

accessibility and usability... The field is derived from or related to

mathematics, logic, linguistics, psychology, computer technology, operations

research, the graphic arts communications, library science, management,

and... other fields." (Taylor, 1977)

Originally, as it began to impact curicula in the

1950's, information science was an add on to the curriculum and courses

were devoted to the application of data processing to library operations

and the automation of internal library functions. Computer related skills

and theory, if they were offered at all, were confined to separate courses,

and the majority of faculty were not required to become directly involved

in the teaching of the automation of various activities they covered in

their courses. They could simply note that such an activity could be automated,

but that in-depth discussion of the topic was to be covered in separate

"automation" courses. Later the concept was accepted and broadened, as

there was a shift away from the focus on institutions, since technological

access to information is no longer institution bound, to that of an attention

to the client and his or her informa-tion needs. It has been pointed out

that "in a metaphorical sense we are moving from a Ptolemaic world with

the library at the center to a Copernican world with information at the

center and the library as one of its planets." (Taylor, 1977) An integrated

approach no longer allows the luxury of separate courses and curicula,

nor is it educationally sound.

All faculty now must be in a position of making valid

judgements about when an automation perspective is appropriate and then

developing an expertise in those selected aspects. Now instruction in computer-based

systems is dispersed throughout the curicula. For example, some components

that started out as a separate course in online database searching, are

now most legitimately integrated into reference and type of literatures

courses.

However, there remains some worldwide disagreement

about whether library science and information science are sufficiently

different or enough alike to warrant being integrated into one concept

and one program. There are philosophical discussions taking place on that

subject in China and Russia, as well as the United States and Thailand.

Most programs are attempting a cohesive consolidation of several components,

drawn from several disciplines, which is synthesized into a program which

is now more broadly defined than "library science" and "information science"

pulled together. Taken as a whole, it is the study of the characteristics

and organization of information; the process by which information is generated,

distributed and used; the relationship between informa-tion systems and

their users; and the study of the functions of organizations and institutions

which are charged with providing the information systems and services required

by individuals and society.

The core of such a curriculum conveys a body of knowledge

regarding the fundamental aspects of the discipline. As such, an identified

core serves as a context and foundation upon which the rest of the curriculum

is built. The new curicula in most programs reflect the electronic revolution

- both in the form of new courses dealing with current developments and

in revisions of traditional courses which now encompass the application

of new technology, where appropriate. North American schools have reached

a point where no student can emerge from a professional school today without

having worked with computer-based catalogs and cataloging, searching and

database construction, bibliographic and numeric networks, and other such

adaptations of technology to library and infor-mation operations and services.

This is also changing internationally as well, because programs are being

upgraded through local initiatives and because international students,

who have studied in North America, are returning to faculty positions in

their home countries.

This trans-border flow of education is most evident

when one considers that almost ten percent of all FTE in North American

programs are now international students, accounting for about 760 students

in graduate programs of library and information studies. Interestingly,

the largest enrol-lments are from Asian countries. One discussion point,

schools must be mindful of educational programs. In that regard, then,

is whether or not technology is culture bound, being tied to the culture

that originated it, and further, whether attitudes toward information access

vary according to the cultural climate. If the answer to those questions

is positive, then schools have a very delicate balancing act in the education

of international information professionals.

Recently there has been so much activity in the technology

arena that it is difficult to keep up, and some even have a feeling of

loss of control. Years ago, Jesse Shera, a sage in our profession, cau-tioned

that "the great danger with which information science threatens librarianship

is the loss of control of the library profession to other, and less competent,

hands. The basic purpose of librarian-ship is not encompassed in the machine,

and there is much more to librarianship than is envisaged in information

science. If we permit ourselves to be mesmerized by the gadget, if we accept

the flicking image of data on a fluorescent screen as knowledge, we will

soon become like those mythical people of many centuries ago who mistook

for reality the passing shadows reflected on the walls of caves." (Shera,

1983)

5. OVERCOMING TECHNOPHOBIA

This caution must be tempered with a recognition

that libraries and librarianship need to adapt, change, grow, and further

diversify. Those actions will help incorporate new expertise and technology

into the strong philosophy of information service. The acceleration of

change in international relations, in communications, in technological

development, in information access, has meant a swifter arrival of the

future in a vastly different form than was expected even yesterday. That

fact is changing the preparation of information specialist-librarians who

must be educated to become: negotiators - identifying needs; facilitators

- providing effective search strategies; educators - familiar with

the literature in all of its formats; and information intermediaries

- providing current awareness services for populations we serve (Stueart,

1982). Educators are in a key position to effect that change, to act as

change agents, to initiate curicula and design programs to meet future

needs of information professionals, and to

build a commitment to change.

Further, it is obvious that there must be better

articulation among researchers, educators and practitioners, particularly

as technology now seems to dictate approaches for all three. "If indeed

we are a knowledge-producing and knowledge-disseminating system, we need

to insure the strength and integrity of the research-education-practice

relationship." (Eisenbeis, 1990) That requires an awareness of and commitment

to change.

As society evolves away from formal communications

patterns, almost exclusively on printed paper, to a smoother interactive

information flow, the technology removes geographic barriers in a global

setting. The ability to communicate instantaneously has created an information

marketplace not limited to a single country or continent. This, too, has

shaped an international curriculum, sensitive to the trans-border flow

of information and attracted a student body committed to those concepts.

Schools strive to make students technologically literate,

so they can independently judge the capabilities and limitations of new

technologies; and to teach them the principles of planning and management,

so they can employ the products of the new information handling technologies

to deliver better services (Malinconico, 1992). Internet and the fax machine

are examples of initial steps at global communication with which students

are acquainted. Online database management and CD-ROM technologies are

as familiar as printed indexes.

But it is not always easy for faculty to remain on

the cutting edge of technological developments, nor for schools to always

afford the costs of new equipment and software or to justify requests which

may become obsolete overnight. Nor is it easy to define the sensitive human-machine

interaction without becoming somewhat skeptical, and without placing some

of the blame for not seriously addressing the problem on the shoulders

of both practitioners and educators. The technology itself continues to

become more sophisticated and powerful, but at the same time requires that

intervention of human cooperation and vision to maximize its potential

in enhancing library and information services. Therein lies the greatest

resistance, the weakest link, and the greatest challenge for educators

charged with educating both those currently in programs, and professionals

who are seeking an updated continuing education component. More than ever

before this also requires a continuing education, or in some cases a re-education,

of faculty.

How to effectively implement educational programs

which prepare new professionals and at the same time develop continuing

education programs for those needing them are the most important, but not

the easiest questions, to answer, because change of attitude demands the

acceptance of new ideas and concept, learning new skills and techniques,

breaking old habits, and altering well-established behavioral patterns

of learners and teachers. For the first time in our profession's history,

that technology outpaces our human endeavors to envision and develop sophisticated

information systems. Educational requirements of the technological revolution

are redefining the competencies and processes required for thought and

communication in those schools. This use brings with it a recognition of

the changes in human interactions and social structures which must be communicated

in the curriculum context. Educators are charged with performing a miracle

by preparing the next generation of information professionals. One only

hopes that faculty have been able to instill a sense of confidence among

students in their technological abilities, while primarily focusing on

concern for people and their information needs, because however impressive

the new technologies, however accelerated the rate of their acceptance,

however revolutionary their long-range consequences for our society, we

cannot ignore the impact of evolutionary change on human behavior (Squire,

1987), and we cannot ignore the need to instill a humane awareness among

graduates.

An added genuine concern is that greater attention

is being paid to computers and their use, at the expense of a respect for

humanistic knowledge and cultural heritage. We cannot allow that to happen,

but we shouldn't view this as a dichotomy; computers do not necessarily

separate us, because technology can be an integrative influence as well

as one of fragmentation. It depends on how the technology is introduced,

and subsequently used.

With all of this technological activity, how do faculty,

students and professionals react? The term technostress has been applied

to feelings of burn out among information professionals even as early as

their days in professional education programs. The major source of technostress

is inadequate training for both hardware and software, and this causes

anger, frustration, and sometimes physical illness. It has been defined

as "a modern disease of adaptation caused by an inability to cope with

the new computer technologies in a healthy manner. It manifests itself

in two distinct but related ways, first, in the struggle to accept computer

technology, and, secondly, in the more specialized form of over-identification

with computer technology." (Brod, 1984) Both of those profiles fit the

field of librarianship and information services. Hopefully, technostress

is being reduced as schools are able to more effectively integrate technology

with the curicula.

An emerging and somewhat related and by no means

an insignificant issue is one of being able to analyze the ethics of information

and the awesome capabilities of future information technology. The assumption

of instilling ethical responsibility, making rational distinction between

means and ends, is becoming a major concern and focus in educational programs.

Schools have an obligation to instill that ethical standard.

6. CONCLUSION

Schools rightfully can be viewed as a key factor

in an evolutionary technology-based process because:

• They maintain a continuous link between the profession

and the expert resources of the faculty which, after all, is the most important

leadership component in the development and maintenance of quality curicula,

the faculty and it's expertise is the curriculum.

• They replenish the profession by recruiting, educating,

and socializing successive generations of new professionals; and

• They generate much of the applied research which

constitutes the expert knowledge and further development of the profession.

There is nothing fundamentally new about those identified

issues. The major difference is in the speed and capacity for information

transfer, and in the continuing development of the complexity of needs,

which require immediate response with a human touch. An attitude of service

to all segments of the population is the most important factor that the

curriculum can impart. Then schools can truly maintain that they are "educating"

professionals rather than simply "training" technicians.

REFERENCES

Lester Asheim, "Education for Future Academic Librarians,"

Academic

Libraries of the Year 2000 . New York: R. R. Bowker, 1977, p. 128.

Craig Brod, Technostress: The Human Cost of the

Computer Revolution. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1984, p. 16.

Evelyn H. Daniels, "New Curriculum Areas," in Education

of Library and Information Professionals, ed. by R.K. Gardner. Littleton,

CO: Libraries Unlimited, Inc., 1987, p. 56.)

Anthony Debons, et. al., The Information Professional,

New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1987, pp. 5-6.

Kathleen Eisenbeis, "An Examination of the Profession

and Discipline, Information Science; The Interdisciplinary Context,

ed.

by J.M. Pemberton and A.E. Prentice. New York: Neal-Schuman Pub., Inc.,

1990, p. 168.

Warren J. Haas, "Information Studies, Librarianship,

and Professional Leadership," Bulletin of the Medical Library Association,

76

(1): 5-6 (January 1988).

J.M Griffith and D.W. King, New Directions in

Library and Information Science Education. Westport, CT: Greenwood

Press, 1986, p. 163.

S. Michael Malinconico, "What Librarians need to

know to survive in an Age of Technology," Journal of Education for Library

and Information Science, 33 (3): 227 (Summer 1992).

Kevin J. McGarry, "The Influence of Technology on

Professional Curicula," ASLIB Proceedings, 35 (2):103 (February

1983).

Jesse H. Shera, "Librarianship and Information Science,"

in The Study of Information ed. by F. Machlup and U. Mansfield.

New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1983, pp. 387-88.

Timothy W. Sineath, "Information Science in the Curriculum,"

Journal

of Library Administration, 16 (1/2): 56 (1992).

James R. Squire, "The Human Side of the Technological

Revolution," in Books in Our Future, ed, by J. Y. Cole. Wash., D.C.:

Library of Congress, 1987, p. 205.

Standards for Accreditation of Master's Programs

in Library and Information Studies. Chicago, IL: American Library Association,

1992.

Robert D. Stueart, "Libraries: A New Role," in Books,

Libraries and Electronics: Essays on the Future of Written Communication.

White Plains, N.Y.: Knowledge Industry Pub., Inc., 1982, pp. 114-15.

Robert Taylor, "Professional Aspects of Information

Science and Technology," Annual Review of Information Science and Technology,

1

(1966):19.

Robert Taylor, "Preface," Libraries in Post-Industrial

Society, Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press., 1977, p. xix.