Robert M. Hayes

GSLIS, University of California

Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA

E-mail: ifx1rmh@mvs.oac.ucla.edu

Abstract: This paper presents a model

-- called the LCM or "Library Costing Model" -- for costing of library

operations and services and then, within the context of that model, it

discusses the effects of new information technology upon costs. The model

embodies a cost-accounting approach to costing based upon the use of "Workload

Factors" for estimating direct labor and associated direct salary costs;

to those are added estimates of indirect salary costs, costs in overhead,

costs for information materials and related direct expenses, and costs

for general administration

This paper presents the LCM or "Library Costing Model" for costing of library operations and services and then, within the context of that model, it discusses the effects of new information tech-nology upon costs.

The effects of new information technology are considered as they relate

to each of those com-ponents of costs. Specifically, the effects on workload

factors and indirect salary costs appear to be negligible except as automation

changes the mix of workloads handled. The effects on overhead are substantial

in expenses for maintenance and for amortization of capital costs of hardware,

software, installation, and conversion. The effects on costs for information

materials and related direct expen-ses are substantial, as electronic forms

both compete with printed forms and add new media to them. The effects

on general administration are substantial in the addition of staffing for

systems work and in the commitment of management time to the strategic

and tactical issues involved in introduction of new information technology.

2. LCM -- THE LIBRARY COSTING MODEL

• Approach to Costing

The approach to costing used in the LCM is an ex post facto cost accounting. That is, cost data reported in a wide variety of ways are reduced to a common cost accounting structure. This approach is in contrast to the typical "time and motion study," in which careful measurements are made of the time actually taken for each of a sequence of operations, and to a "total cost" approach, in which reported costs for an operation are taken as a whole and simply divided by the total work-load. Finally, it is in contrast to a true cost accounting, in which data are recorded and analyzed in standard cost categories at the time they are incurred.

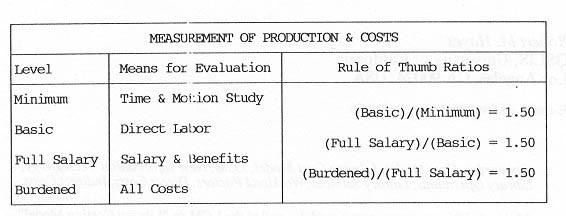

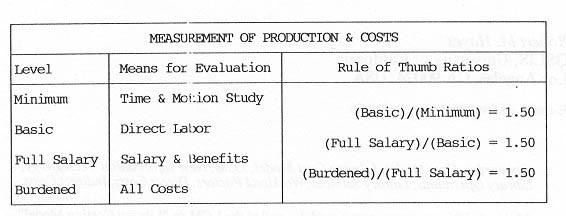

The following schematic summarizes the approaches together with some "rules of thumb" for the ratios among them:

It is important to recognize the differences among these approaches,

since they result in drama-tically different estimates of cost that are

difficult to reconcile. It is beyond the scope of this paper to detail

those differences, but to summarize: The most accurate and complete is

a true cost accounting based on records at the time costs are incurred

and properly allocated. The most detailed will be the time and motion study,

but it will usually account for only the most specific costs, not dealing

with benefits or with allocable costs since it measures only the actual

time in performance of a defined set of tasks. At the other extreme, the

total cost approach provides no detail and no means for analysis of functions;

it is the least accurate of the methods and may grossly mis-estimate the

costs, both under and over, in ways that make it impossible to calibrate.

The ad hoc cost accounting approach used in LCM is an effort to establish

a standard means for dealing with quoted costs that will include all components

in a framework that permits analysis.

• Estimates of Direct Labor: The Use of Workload Factors

The LCM uses a matrix of "workload factors" as the means for estimation of the staff required to handle a defined workload, measured in appropriate "units of work." For each of a set of library functions and subsidiary processes, such units of work have been defined. The workload factors then are expressed as percentages of FTE (yearly full-time equivalent) staff for the performance of 1000 (K) units of work for each library function and subsidiary process. The LCM incorporates default values for the workload factors, as will be shown below, but you can modify them to reflect your own library experience. The default values currently used in LCM are, with very few excep-tions, identical with those first published in 1974.*

Measuring the workload factors by FTE per thousand transactions may seem unfamiliar. An alternative means for expressing them could have been "minutes per transaction." To translate from one to the other, note that a working year is almost exactly 100,000 minutes (i.e., 40 hours per week for 42 working weeks is 100,800 minutes), so 1 minute per transaction would be .01 FTE per 1000 transactions.

The default values for the workload factors were developed by an interactive process that involved well over one hundred libraries, of all kinds and sizes, over a period of many years. The one uniform component of the process was the fundamental cost accounting structure into which the observed data were fit. Estimates at a given point in time were matched with actual and/or reported costs for a visited library and operations within it as of that time. If estimates matched library costs to within about 10%, they were regarded as further confirmed.

But if the estimated costs differed by substantially more than 10% from the reported ones, they were carefully examined for possible reasons for the differences. Were they caused by flaws in the workload factors; if so should there be changes in them? Did they reflect differences in functions and processes; if so should there be additions to them? Were there differences in efficiencies; if so, how should the efficiencies be treated?

Beyond the use of actual data from visited libraries, other means were used to determine de-fault values. A number of time and motion studies were conducted to determine production rates on typical generic library activities. The rich array of published data were reviewed and reduced to a consistent accounting structure. Analogies were drawn among various kinds of operations, both within libraries and between them and industrial and commercial counterparts. To put these various sources of data into a common framework, the rule of thumb ratios (shown above in the discussion of levels of costing) were consistently used for conversion to fully burdened estimates.

The default workload factors in LCM are consciously and deliberately used with minimal precision -- typically on the order of 10%. For example, Circulation Record Keeping per 1000 Circulations sums to 0.06 FTE, not 0.0575 or some comparable value of high precision. This reflects the fact that there is great variability among institutions and, even within a single one, differences in the qualitative character of the workload. It would be spurious to imply high levels of precision simply not warranted. As a result, there is no reason to anticipate that use of these default values in a given library will match actual data any closer than the precision implies -- i.e., within say 10%. It is for that reason that the LCM provides means for you to change the defaults to your own estimates. You may have sufficient confidence in your data to warrant use of workload factors of higher precision than is represented in these default values.

Details about the functions, processes, related units of work, and default workload factors as included in the LCM will be presented in the following sub-sections, each focused on a category of library operations or services.

In each case, the workload factors are associated with levels of staff ("Prof," for professional, "Non-Prof," for non-professional; and "Hourly" for students or other casual labor). The assign-ments shown are part of the assumptions underlying the default values. Thus, for example, the workload factor for the process of selection (i.e., 0.25 FTE per 1000 titles selected) is assigned to "Prof" under the assumption that such work is likely to be a professional responsibility. Of course, the determination of appropriate levels of staff for various processes will differ from library to library, so LCM permits you to modify not only the value of the workload factor but the assignment of it as well.

Technical Processing: Units of Work & Default Workload Values

The following are the Units of Work used in the LCM model for technical processing functions:

Acquisition Selection K Titles/Year

Order, Invoice K Orders/Year

Cataloging All Processes K Titles/Year

Serials All Processes K Titles/Year

Physical Handling All Processes K Volumes/Year

Acquisition Select .25

Order .20

Invoice .20

Cataloging Original 1.60

Copy .20

Maintain .25

Serials Receiving .10

Records .10

Physical Handling Receiving .02

Labeling .06

Cataloging. These are processes in cataloging: Original and copy cataloging and catalog main-tenance (such as authority files and corrections). If the proportion of cataloging that is original is not specified, the LCM calculates it based on the size of the collection.

Serials. These are processes in receiving of serials, including record maintenance, claiming, and physical handling. Acquisition and cataloging of serials are not included here but instead are treated as part of the workload for those functions.

Physical Handling. These are processes in receiving of monographs, including physical pre-paration of them for shelving and for subsequent use.

Preservation: Units of Work & Default Workload Values

The following are the units of work for preservation functions:

Binding All Processes K Volumes/Year

Reproduce All Processes K Volumes/Year

Conserve All Processes K Volumes/Year

Binding Identify 0.06

Prepare 0.10

Bind 0.00

Reproduce Identify 0.06

Assess 0.06

Biblio 0.04

Prepare 0.20

Copy (Film, Photo) 0.00

Conserve Levels 1, 2 0.15

Level 3 2.50

Conservation Levels 1,2. This includes Minor Treatment (such as page repairs, pamphlet binding, and making of pockets for loose parts like maps) and Intermediate Treatment (such as extensive repairs, cloth case re-backing, rebinding). Such treatments can be completed in two hours or less.

Conservation Level 3. These are major conservation treatments, including de acidification, reconstruction and repair of historical binding and individual pages. They involve complexity both in the procedures and in the protection of the original, and are warranted only when there is subs-tantial value in the item itself.

Copying. Preservation copying (whether by photocopying or filming)

is the means for pre-servation of the information content when the value

of the original does not warrant saving.

Information Services: Units of Work & Default Workload Values

The following are the Units of Work used in the LCM model for information

service functions:

Circulation Records K Circulations/Year

Reshelving K Uses/Year

ILL Borrowing All Processes K Borrows/Year

ILL Lending All Processes K Lends/Year

Reference K Hours/Year

Information Skills K Faculty/Year

Circulation Records .03 .03

Reshelving Calculated

ILL Borrowing Biblio .20

Handling .10

Records .20

ILL Lending Biblio .05

Handling .10

Records .20

Reference .20 .20

Information Skills Instruction 5.00

If workload data for information service functions are not provided, LCM uses calculations to determine them. Of course, if workload data are provided, they are used instead of the calculations.

Circulation. These are processes involved in the circulation of materials, including record keeping and reshelving. LCM assumes record keeping is measured by regular circulation, not counting renewals or reserve book uses. The workload for reshelving, however, should include that for in-house use.

If circulation data are not provided, LCM assumes that circulation and other uses are deter-mined primarily by the size of the collection and, in fact, that the total use is about equal to the size of the collection -- up to a limit, at least. That is the calculation currently included in the LCM.

Note that the workload factor for reshelving is shown as "Calculated." In the original publication of workload factors, it was taken as a constant, but it must be recognized that this function, perhaps more than any other, is a function of the size of the collection. LCM therefore calculates the workload factor based on Holdings.

ILL Borrow and Lend. These are processes involved in identification of materials needed and of the potential sources for them, communication with those sources and the related record keeping, getting the materials at the host, delivering them (or copies), returning them, and accounting for the activity.

Information Skills. These are processes in providing students and faculty with guidance in access to and use of library and information materials to support instruction and research. Informa-tion Skills activities represent a broad range and depth of responsibilities -- "bibliographic instruc-tion," guidance to CD-ROM use, consultation and liaison with academic staff. The staff for these functions therefore need to be separated out of those for reference in general. The estimate of 5 FTE per 1000 faculty was derived from examining a large number of institutions.

General Reference. LCM measures reference by HOURS of staff service, determined from the number of stations multiplied by the yearly hours per station. If the number of reference stations is not identified as part of data entry or in files, LCM assumes that the workload for general reference work is determined by the size of the collection (especially as reflected in the number of branch libraries) combined with the size of the using population (measured by number of students or, as actually used, the number of academic staff). Based on analyses of data available on total library staff (less those assignable to other functions), the following formula is currently used in LCM:

(Reference Staff Stations) = (.010*HOLDINGS/1000 + .010*FACULTY)

There is one reported estimate to the effect that university reference work involves about 13.5 hours per week of time for a typical professional reference librarian; the .25 FTE per 1000 hours would be the equivalent of 13.5 hours per week -- that is,

(Weekly Hours)/(Professional Reference Staff) = (.25*1680)*(1680/1000)/52

= 13.5

Overhead

The next major component of the LCM cost accounting model is "overhead." In general, over-head or, as it is frequently called, "indirect" or "burden," includes those costs that cannot be directly attributed to "productive work." That in no way means that such costs are not necessary or signi-ficant. It simply means that it would be difficult or irrational to attempt to associate them directly with productive work. Supervision, for example, is clearly necessary, but it in no way in itself produces catalog entries, binds volumes, films pages, or does the actual work whatever it may be. Holidays, vacation, and sick leave are necessary components of a compensation package, but usually no productive work is accomplished during such time.

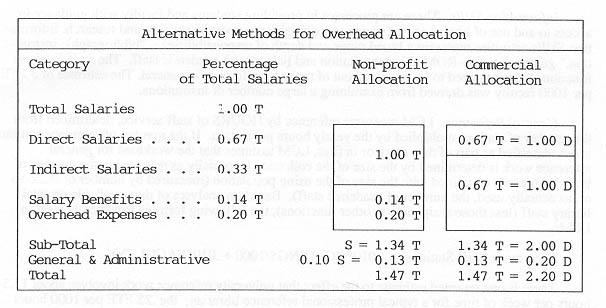

The purpose of "overhead" or "indirect costs" is to account for these kinds of costs. A typical rule for doing so is "proportional to direct labor costs," and that is the rule used here. Some illus-trative values for overhead are presented in the following table, in order to show two alternative means for presentation of the overhead accounts. (The percentages shown are merely for the purposes of illustration, to show how each enters into the calculation.)

It is important to recognize both the differences between the two and the essential equivalence of them. One, which treats "total salary" as the foundation, is typically used in "not-for-profit" institutions; the other, which treats "direct salary" as the foundation, is typically used in commercial contexts. Whichever may be used, the total costs (leaving aside allocation of profit or amortization of capital costs) must be the same, if efficiencies are the same. And, with all due respect to the much vaunted efficiency of private enterprise, there is nothing inherent in the tasks here that implies greater efficiency as a result of different means in accounting for costs. For a variety of reasons, though, the commercial accounting model is the one used in the LCM. In the following sub-sections, each of the major categories of overhead will be described and then the relevant data from U.S. site visits will be summarized.

Indirect FTE. These reflect the role of staff time needed to supervise and support the work of the direct FTE involved in actual performance of library operations and services. They include time involved in training (though not that of staff doing the training). They include provision (unallo-cated time) for all other time spent on the job but not carrying out actual direct work. Finally they include provision for holidays, vacation, sick leave, and other time-off.

Supervision and Clerical Support. Any operation must have supervision (to schedule and assign tasks, to evaluate performance, to provide assistance with problems) and that usually implies clerical support (not clericals as part of direct labor, but in administrative functions). Even a "one person" operation requires planning and scheduling of work, reporting and evaluation of perfor-mance, correspondence and record keeping; in such contexts, supervision and clerical support must be treated as a portion of the single person's time. But in many-person contexts, these overhead items are critical and should be carefully and separately accounted for.

What is the portion of time required for supervision? Military and industrial experience, over centuries, has established a standard "span of control," represented at the simplest level by the squad -- a group of 8 to 12 persons under a non-commissioned officer as supervisor. That ratio, of 1/8 to 1/12, appears to be quite common and, given no other data, was the original basis for LCM over-head rates, as presented above. The examination of libraries generally has confirmed the validity of that ratio of supervisors to direct staff FTE.

From groups of all kinds within libraries visited -- preservation departments, technical services departments, and a variety of others -- proportions for supervisory staff to total staff appear to be uniformly 12% (plus or minus 0.5%) -- a ratio of roughly one supervisor to 8 staff, not far from the military and industrial experience in span of control. In very small groups, descriptions of duties clearly show that persons identified as "supervisors" spend a high portion of time in direct, produc-tive labor, and there is no reason to treat the ratio of supervision time to direct labor time in such circumstances as substantially different from 1/8. In conformance with the general principle of using default values of minimal precision, the value used for supervision is .10 (i.e., one supervisor for every 10 direct FTE). Neither ratio, though, recognizes the fact that the supervisors are univer-sally paid at higher salaries. As a result, the proportion of salary dollars is dramatically different, being nearly twice -- about 20%. Again, the proportion was quite uniform, differing by at most 0.5% either way from 20%.

Training. "Training" is a significant component of overhead. There are a number of sources recommending that 2% to 3% of total staff costs should be committed to training, so this overhead function has been estimated at 3%.

Unallocated Time. In every operation there is time of staff, who may be, in principle, assign-ed to direct work, which should be assigned to indirect or overhead time -- what is called "unallocat-ed" time (i.e., not allocated to direct, productive work). For example, staff attend meetings; they participate in orientation; they must deal with visitors that ask for data about operations and costs; they attend union meetings and professional society meetings; they assist in training programs. There are innumerable demands on staff time that fall into this category.

Unfortunately, there are few data that can be used even to estimate unallocated time. There apparently are no practices in libraries for keeping track of it and certainly none to account for it. The kinds of activities involved may or may not be recognized as reducing the time for direct, productive work. Surely, some, such as time to attend professional society meetings, are recog-nized; but even for them, there is no evident record of the total time commitment. Others, such as time to assist in training and for internal meetings, appear simply to be accepted as part of the work-load, even though they clearly are not specific to the workload tasks. Of all of the categories of overhead, it is the one most likely to result in dramatic increases in indirect costs and in reduction in productivity. Given that, it would seem valuable to establish at least some bench-marks for acceptable ranges of values.

Benefit Days. A major component of overhead are holidays, vacation,

sick leave, personal leave, and sabbatical. There were fairly wide variations

among these categories, but again the modal cluster was clear and narrow.

Summary of Benefit Days

_________________________________________________________

Category Days Percentage of YearHolidays 11 4.2 %

Vacation 22 8.4 %

Sick Leave 16 6.1 %

Total 49 18.7 %

First, the range for holidays was from 10 to 13 days, but the evident

mode was 11 days per year. Given 260 days total per year (52 weeks at 5

days per week) as the total salary period, at 11 days per year holidays

represent 4.2% of total salary.

Second, the range for vacation time was from 15 to 25 days per year. There was no evident modal cluster, but the mean was 22 days (about four weeks). For 260 days total per year, that represents 8.4% of total salary.

Third, sick leave and personal leave are evidently treated as part of a combined package by most, if not all, institutions even though in principle they should not be substitutable. Combined, they cluster around 16 days per year which, for 260 days total, represents 6.1% of total salary. Of course, the extent to which these are in fact used varies much more than holidays and vacations, so the actual cost of sick leave and personal leave may be different from the stated policies.

Fourth, sabbatical leave or some equivalent "leave with pay" is frequently a perquisite for professional positions, especially when they have faculty status. Typically, a sabbatical might be accumulated at the rate of half a year to one year every seven years. If sabbaticals were taken at that rate, the benefit days would be the equivalent of 7.0% to 14.0%. The facts, however, are that sabbaticals seem to be rarely taken even in institutions where librarians have faculty status. The result is that this benefit has negligible addition to overhead.

As the table above shows, the total is just about 10 working weeks,

about 19% of the 52 weeks of a year, that must be paid for benefit days

for full-time employees. However, again the high percentage of FTE filled

by students has a dramatic effect on benefit days, since vacations are

not accumulated by them and they are not likely to be paid for holiday

time, unless they actually work on those days. Given that about 25% of

the staff FTE are students, the result is a significant reduction from

the total of 19% to a net total of 14% (i.e., the 19% applies only to the

75% of staff who are full-time).

Salary Benefits

Categories of Benefits

Social Security 7.50 % salary

Disability 1.00 % salary

Unemployment 0.50 % salary

Fica 3.00 % salary

Life insurance 0.50 % salary

Medical insurance 4.00 % salary

Tuition 1.00 % salary

Retirement 8.00 % salary

Total 25.50 % salary

These provide for salary related costs other than the salary itself or the various days off. They include social security (employer's contribution), other retirement costs, work-men's compensation, medical and other insurance, employer paid payroll taxes, etc. The categories of benefits, though not all of them are necessarily defined by any one institution as part of their benefits package, are as follows (in each case, the figure reflects the employer's contribution, not that of the employee):

The totals for salary-related benefits in the U.S. has a very wide range

but the modal cluster is apparently just about 25.5% of total salary. The

range is from 21% to 31%, but the average is 25.5%, exactly at the modal

cluster mid-point. Furthermore, the basis for the quoted values varied

from statements in documents on benefits policy to ratios of expenditures.

The latter will result in substantially lower actual percentages because

of the lessened benefits for students and other hourly employees. In any

event, the average of 25.5% is most representative of the benefits policies,

especially in university contexts.

Overhead Supplies

Supplies and expenses are treated as a central budget in libraries and

not allocated to individual departments in any manner that permits association

with either functional activities or even general costs. Data were obtained

on which to estimate the percentage of total operating costs (not counting

direct expenses associated with materials and processing or binding of

them) for some components of Overhead Expenses, as percentages of total

operating costs:

Electricity 3.0%

Telephone 0.5%

Postage & Stationary 1.5%

LCM uses a nominal 5% of total salary for this category.

Space, Maintenance, Utilities

These overhead items turn out to be exceptionally difficult to account for. The cost for construction is uncertain; the time period for amortization is undefined; the space allocable to speci-fic functions is uncertain. The cost for maintenance depends upon the nature of the space occupied but is never clearly defined; the basis for quoting the cost of maintenance varies widely among insti-tutions; the extent to which it in fact is provided is uncertain. The charges for utilities are usually buried in institutional budgets; they vary widely and unaccountably by the type of space occupied. However, estimates for construction currently are quite focused around a modal value of $150 per square foot. If we use an amortization period of 20 years, that's $7.50 per square foot per year. Estimates for the costs of maintenance are quite narrowly clustered around $5.00 per square foot per year. Finally, data for space occupied by various functions suggests that each person requires about 250 square feet (including both space actually occupied and the necessary "public space"). The result is a cost per year, per person, of $3125. That is about 14% of the average current salary.

Maintenance of Equipment and Amortization of Capital Expenses

In commercial and industrial organizations, capital expenditures for equipment are usually amortized over an appropriate period of time -- five years, for example. The purpose is to provide the accounting basis for accumulating capital for replacement of the equipment as it becomes obso-lescent or obsolete. The amortized costs, together with those for maintenance of the equipment, are typically included as part of overhead and in that way included in the costs of products and services.

Unfortunately, most not-for-profit organizations treat capital expenditures as expenses rather than as investments and do not accumulate funds for replacement in that way. The result has frequently been serious difficulty in keeping pace with the developments in information technology.

University Overhead

A final potential overhead item is the university overhead. However,

important though it is, there are great variabilities in it, great dependence

upon the basis for allocation and institutional specifics, and much overlap

with the library's own budget. As a result, no effort has been made to

estimate either the magnitude of institutional overhead or the basis for

allocation of it.

Costs of Information Materials and Direct Expenses

The LCM provides means for including costs for information materials such as books, jour-nals, audio-visual media, CD-ROM and other electronic forms, and multi-media systems.

It also provides means for including costs for direct expenses associated

with library opera-tions and services. Such costs are involved in acquisition

and processing of information materials -- for bar-codes, jackets, labels,

book cards, etc.; in use of bibliographic utilities as part of cataloging;

in use of bibliographic utilities for searching and in packaging and mailing

to support interlibrary borrowing and lending; in on line searching to

support reference and bibliographic services.

General and Administrative -- G&A

The operation of a major research library requires central administration of a high order, covering a wide range of responsibilities that, by their nature, make no direct contribution to the production of library services or to operations. They are nevertheless essential functions, without which the library could not operate.

To be specific, the following typically are included in these "general and administrative" functions:

• Leadership. This clearly is the most significant function in research library administration. It sets the objectives, the priorities, the style for the library. It determines how and where resources are needed and will be committed. It creates working relation with the institution served by the library.

• Personnel Administration. The functions of hiring, evaluating, promoting, and maintaining records on staff, and more generally providing all that is necessary for personnel administration are a fundamental G&A responsibility. To some extent, the research library may call on the larger institu-tional administration for assistance, but in all major research libraries the library itself provides for all significant aspects of personnel administration.

• Budgeting and Accounting. As multi-million dollar operations, the research libraries must maintain complete and dedicated services for financial management. Book funds, personnel funds, project funds -- all must be carefully and completely accounted for. These must be handled at the G&A level.

• Public Relations and Publicity. Every major library maintains an extensive program of communications, publicity, and public relations. This kind of G&A activity is essential for develop-ment of financial support of the library, but it is even more essential to the university because of the central role of the research library in institutional reputation.

• Collection Development. The central library administration can play a substantive role with respect to collection development. This reflects the importance given that function, especially with respect to gifts from major donors, in which the tasks of collection development are inseparable from those of financial development. There is almost no rational means for separating out these productive functions from the general and administrative ones.

• Automated Systems. Systems analysis, programming, computer equipment and facilities management, associated personnel, local area networking and CD-ROM accessing, relationships with central campus computing facilities -- all of these have now become essential components of academic library operation. By their nature they are clearly part of G&A, since they apply across the board of library operations rather than being specific to any one function.

• Other Kinds of Support. It is possible that other responsibilities,

such as legal counsel services, might be included within the library's

administration and therefore be part of G&A.

Should G&A be Included in Costing?

With this definition of "general and administrative functions," the question is whether their costs should be included in the cost assessment. Some would argue that these are costs that will be incurred by the library whatever the decisions may be. They see G&A costs as fixed and would treat them as "marginal costs," without any allocation of them. LCM assumes that G&A costs may need to be considered and properly allocated, proportionally to the direct and indirect costs involved.

Among the categories of information about academic libraries, this can be among the most difficult to obtain as unequivocal, uniform data. In some cases, the central administration is defined to include heads of branches or operational departments in ways impossible to separate out. In other cases, the central administration, as defined, clearly does not include all of the G&A functions; yet, it may not be clear where those functions are provided.

However, the available data show that G&A -- the university librarian's

office, to be specific -- averages about 15% of total operating costs (not

counting costs of acquisitions). For a variety of reasons, though, the

default value has been chosen at 10% of operating costs.

3. THE EFFECTS OF NEW INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

The effects of new information technology upon costs of library operations and services will now be discussed using the framework of the LCM components in the following order:

• Effects on costs for general administration

• Effects on costs for information materials and direct expenses

• Effects on overhead costs

• Effects on indirect salaries

• Effects on workload factors and associated direct salaries

• Effects on costs for general administration

For at least the past two decades, automation and the effective utilization of new information technology has been a major focus of strategic management for academic libraries. It has required the attention of library directors in order to obtain the funds required, hire the staff needed to imple-ment, control the processes in acquisition of hardware and software, allocate the space and operating resources needed to house them, participate in cooperative efforts to minimize costs by sharing bibliographic data, deal with the needs of staff in adapting to the changes in operations, inform the academic community of users and work with them to assure their needs are met. Taken together, these tasks may well have consumed as much as 25% of time for academic library directors.

Addition of staff -- systems staff and operating staff -- has been required to make the necessary technical decisions and to implement and manage the results. The percentage of G&A staff involved in such efforts appears to be about 10% of total general management for a library. Frequently their work required hiring consultants and short-term project staff to support the internal staff.

It is evident that new information technology will continue to require at least comparable levels of commitment at the highest levels of academic library management. The costs for doing so will probably be in the range of 10% to 15% of the G&A budget, or about 2% of total library budget.

• Effects on costs for information materials and direct expenses

The acquisition of new information technology materials is just beginning, but already CD-ROM acquisitions are part of the budget of every academic library and many of them are acquiring magnetic tape files for loading into local systems for access though campus on line public access catalogs. As newer materials, such as multi-media systems, become widely available they will add further pressures, and within this decade new technology information materials will probably require about 10% of the library's acquisition budget.

• Effects on overhead costs

If proper accounting for capital costs -- in purchase of hardware and software, in conversion of data files, in installation of facilities -- were included as part of overhead, the effects would be substantial. Amortization of such capital costs might average about $500,000 per year for an average ARL library -- about 5% to 10% of total budget. The effect would be a substantial increase in the overhead rate.

• Effects on indirect salaries

Will new information technology affect indirect salaries? That is a question of some current debate. Some have argued that information technology can significantly reduce the need for middle management and for supervision in general. Their view is that distributed computing will permit the elimination of layers of management, replacing them by inter-communication through shared data files.

However, there are even more persuasive arguments against that view. Middle management is needed to assure that data are valid. They are needed because "span of control" is still subject to the reality of what persons can do. They are needed as means to communicate between strategic, tacti-cal, and operational levels of management. They are needed as the training ground for top levels of management.

• Effects on workload factors and associated direct salaries

The default values used in the LCM were first published twenty years ago, but they remain essentially the same in its implementation today. During that time, though, automation has become a standard part of library operations and services. So repeatedly, as the LCM has been presented to librarians, the question has been asked, "Hasn't automation affected the efficiency of staff? Why haven't the workload factors changed?" On the surface, that question is reasonable. In fact, it is being repeatedly asked in commerce and industry where expectations of improved clerical produc-tivity as a result of automation have almost never been met.

The evidence from application of the LCM to data from hundreds of libraries over the past thirty years is that automation does not fundamentally change the efficiency of human operations. Persons still keyboard data at about the same rate; they make errors at about the same rate; they make decisions at about the same rate; they handle physical objects at about the same rate. Since these are the things that the workload factors measure, there is no reason to expect them to change.

What does change is the mix of tasks performed. That is best illustrated through cataloging, in which the mix of original cataloging and copy cataloging has dramatically changed in the past twenty years. The effect of bibliographic utilities has been profound and has led to dramatic reductions in the staffing of technical services.

One effect of new technology may lead to change, not so much in the workload factors them-selves as between them and the overall operation. It is the potential of "telecommuting," in which work may be done remotely thus reducing time lost in transportation and increasing the morale of staff.

Even more important, though, is the effect on services and on the users.

It permits the library to provide services that would otherwise be inconceivable,

vastly increasing the value to the users, and increasing their productivity.

The result has been increases of staff requirements for providing information

services and for educating users in the opportunities provided by the new

information technology. It is this that makes the new technology worthwhile.