PANEL ON EDUCATION/TRAINING RELATED TO NIT AND GII

Customizing the Education of Information Professionals: The Paraguayan Experience

Herbert K. Achleitner

Emporia State University

School of Library & Information

Management

Emporia, Kansas 66801, USA

ACHLEITH@ESUVM1.EMPORIA.EDU

Introduction

The information society emerging today is driven by the confluence of compu-ters, communications, visual information, and knowledge. Information networks provide the necessary linkage among these technologies creating a dynamic environment in which ideas and information brush against each other, thus sha-ping our postindustrial culture and impacting our lifestyles. These technologies, because they have become such an integral part of our daily existence, are not only shaping our personal lives, but also the lives of our local communities, our nation, and the global community. Although technological progress has been an intimate part of the Western worldview, developing countries are reacting quite differently to the technological forces that impact their economic, political, and social development. Stability rather than progress and change has been the primary focus of government activity. The fact is, although in many developing countries the old centrally planned economic model is discredited, a national consensus does not exist for a shift toward liberal economic reform. The lack of popular support for change and the pressing economic needs of most of the populations leave little time for fundamental restructuring of society. It may be left to the information professionals as knowledge providers to become the bridge between those elements in a developing society opposed to change and those that see change as inevitable and even beneficial to democratic development.

The New Environment

As the networked world becomes a reality, it becomes necessary to rethink the role of information, libraries, information systems, information professionals, and private and public institutions. Not only is information technology going through a paradigm shift, but so are developing countries. The new information technolo-gy is moving toward an open, user-centered, and networked computing system. The technology empowers the user and distributes information widely and easily. For example, everyone in an organization has the potential to become part of the decision-making process, and noone is isolated from the group. The integration of text, voice, and visual information in various formats becomes seamless. However, this trend of easy access to information and openly sharing information runs counter to the autocratic tradition of controlling information. The new geopolitical order is also becoming open, networked, and information-based. Paraguay's decision to join its more powerful neighbors of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay in an economic union (MERCOSUR), in which all tariffs have been eliminated as of January 1995, means abandoning an economic model of autarky. Instead of economic self-sufficiency, hemispheric regionalism has become the goal (Hurrell, 1994). From a historic point of view, regional cooperation and, therefore, the need to overcome ancient quarrels is quite an achievement. This means close coordination of economic policy as well as continuous exchange of data and information. For Paraguay, this change in policy means more volatility in its economy and greater openness to a multipolar world and, for the old elite, greater potential for social, political, and economic instability.

The opening of world markets, competition, and the advances of information technologies is bringing about a relentless restructuring of national economies. Although in many Latin American countries the agrarian and industrial sector will continue to play a dominant role, cooperative arrangements such as between Chile and Argentina will make these countries eventually global players and economically more viable. Chile has become an important model for economic development for the rest of Latin America. What is particularly critical for deve-lopment are Chile's high-tech companies who are forming cooperative ventures with other Latin American countries (Naisbitt, 1994, pp. 314-317). The goal for any joint business venture today is for the rapid transfer of information; the benefit, however, is information technology transfer and the resultant building of a local as well as a transnational information infrastructure.

Networked World

A dominant trend in the 1990s is toward networked information systems, systems that can function in real time, retrieve appropriate information for rapid decision making from multiple sources, thereby reducing time and space dependencies (Tapscott & Caston, 1993, p. 8). Global manufacturing is illustrative of this trend toward a single worldwide marketplace. The emphasis is on the expansion of ever larger trading zones. NAFTA is contemplating adding Chile and other Latin American countries', the European Union recently added Austria and Sweden to an already very large trading block; and countries such as Bolivia are knocking at MERCOSUR's door. Free-trade zones and the removal of tariff barriers make possible the globalization not only of markets, but also of cooperation and com-petition. This network of worldwide customers, suppliers, and supportive struc-tures such as transportation and banking systems results in an around-the-clock operation. Globalization is possible because of the enabling effect of information technology, which not only allows for restructuring, but creates new models for doing things.

A new global order is being built by information technologies. Computers and telecommunications systems can carry text, voice, data, and images anytime, anyplace, by anyone. Without those capabilities the modern economy could not function. Yet, when one peers beyond the developed world, the availability and use of information technology is not the same. Ching-chin Chen (1994) aptly observed that in our world there is a "dichotomous information environment" from the high-end network computing to the most simple application of techno-logy (p. 67). As we discuss the implication of constructing a Global Information Infrastructure (GII), we are well advised to consider this unequal situation in planning and policy forums. History has taught us that if inequality in wealth and power are ignored, the consequences can lead war and revolution. A disequili-brium in the spread of information technology and the concomitant access and use of information may also have the possibility for discord.

Development of a global network is hampered by limited information deve-lopment in many Latin American countries. Most lack a well-developed library system, have few national networks, and have limited access to the Internet (Lau, 1994, p.19). Paraguay, a founding member of MERCOSUR, illustrates rather well the situation of countries at the beginning of development. Emerging from a succession of authoritarian regimes, 1989 was a turning point with the overthrow of a 35-year-long dictatorship, ending a succession of authoritarian regimes. The economy was primarily agrarian and self-reliant. The economic situation can be summarized as chaotic: a large public sector deficit, inefficient state-run indus-tries, multiple exchange rates, and a financial sector that was poorly regulated (Achleitner & Caballero, 1994).

Joining MERCOSUR provided a direction for economic policy as well as an acceptable means for making tough economic policy decisions. It created the need for a stable government that was capable of making sound economic deci-sions and able to collect and share reliable data in such areas as transportation, insurance, government debt, inflation rates, and so on. This required the collec-tion of accurate data and the sharing of information within government agencies and with the MERCOSUR partners.

An analysis of the information dissemination capabilities of Paraguay reveal-ed a lack of a government information policy. Rather than encouraging the flow of information, the decades of dictatorship encouraged suppression, distortion, and wholesale destruction of information. Libraries and archives are not valued nor viewed as important to the national development. For example, the last item added to the National Archives was in 1920, and what has been stored is slowly disintegrating due to the lack of funds and technical knowledge in preservation techniques. A similar situation exists in the National Library, where government money has been allocated in the national budget, but not distributed (Achleitner & Caballero, 1994, p. 117). The absence of adequate library service mirrors the attitude of the government toward the dissemination of information: Access and use of information was the prerogative of a few powerful individuals and not the public. What most governments in developing countries fail to realize - with the exception of Chile - is that information is a resource and a commodity critical to a nation's well-being. The knowledge cycle, that is, creation, production, dis-semination, organization, storage, utilization, and preservation of information, has been part of human activity since the advent of the printing press and is well developed in advanced industrial countries. The picture in developing countries is not complete.

Knowledge Management

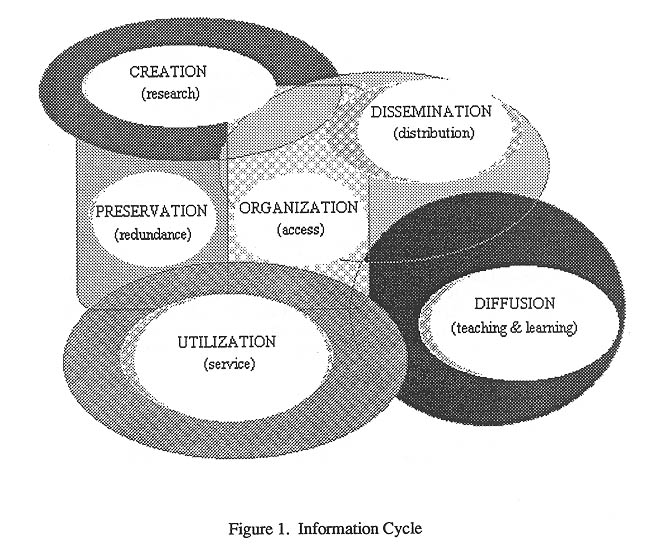

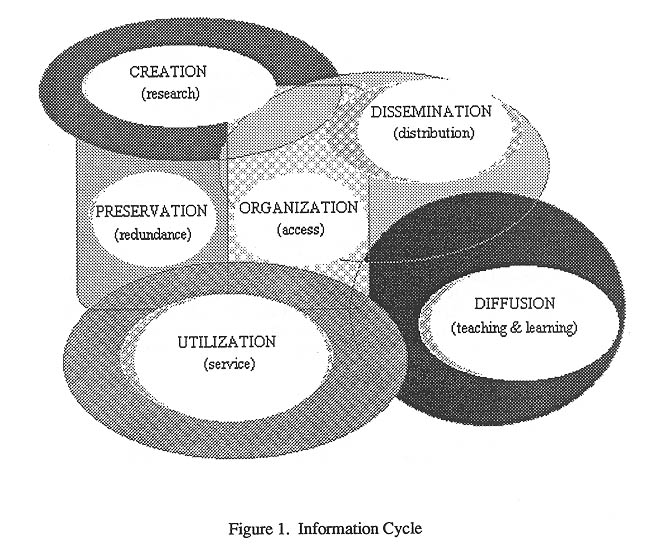

Knowledge management is the responsibility of society as a whole. This in-volves government officials, private sector, educators, scholars as well as the public. There has to be a public commitment to acquiring, storing, organizing, and making accessible a society's knowledge base for current and future use. But knowledge management goes beyond just this process and involves the entire information transfer cycle, including the structuring, restructuring, representation, repackaging, distributing, and use of information (Lucier, 1990, p. 21). The information cycle is a dynamic interactive process that is nonlinear and functions on a feedforward principle; that is, all components of the "cycle" interact and converse in time and space with each other. It can be best described in the Figure 1.*

Information Cycle

According to Nelson (1981), knowledge is created in a cultural context influen-ced by politics, economics, and technology. In the case of Paraguay, we have seen that government policy is hostile toward knowledge creation, providing little in terms of resources and human capital. Furthermore, a self-sufficient, inward-looking economy has limited need for both internal and external information. Requirements for information technology is minimal.

Dissemination of information implies the one-way spreading of information so that the potential user can find and acquire information and learn about options

(Klein & Gwaltney, 1991). Although library services and resources are in a dismal state in Paraguay, access to newspapers -- domestic and foreign radio and television -- has greatly improved in the last few years. Internet service is becoming available, albeit to a select few. Access to foreign databases is being considered.

The diffusion of knowledge is most problematic. Currency, accuracy, and understandability are all issues that impede the diffusion of knowledge. Govern-ment policy discourages diffusion. For example, at both the National and Catholic Universities, such disciplines as history, sociology, anthropology, political science, and economics are not offered. These disciplines are viewed with suspicion and judged dangerous to the internal stability of the state. With-out these key disciplines engaged in an intellectual discourse, the diffusion of knowledge can only take place incompletely. Stories abound of the former dic-tator General Stroessner changing census statistics to fit his image of Paraguay.

Another critical system failure is in the organization of national information. In effect, Paraguay does not have a national bibliography. Although there has been an attempt made by the director of the Catholic University library to collect such information, she neither has the resources nor support to sustain this effort. In addition to not knowing what information exists internally, special collections on Paraguay held in American research universities have never been inventoried.

Knowledge utilization's goal is to increase the use of knowledge, solve pro-blems, and improve the quality of life (Backer, 1991). This becomes difficult when dissemination and diffusion are not valued, research is neither encouraged nor funded, and the values imbedded in the culture tend toward hiding, distorting, and destroying information.

The picture that emerges from this brief survey is not a pretty one, but not unusual for countries in the early stages of development. Yet, the requirements of a global economy call for the building of both a sound civic culture that moves society toward the building of democratic institutions and a tolerance for change. Equally important is the development of an information infrastructure that puts the information cycle on a sound footing. What is required from the government, the legislature, the private sector, and the citizenry is a partnership to develop doable strategies and policies for building a national information infrastructure that can be linked to the GII.

What Is To Be Done?

Building an information infrastructure in a developing country in which little in terms of information systems exist is a difficult task. It is made more difficult because of the scarcity of financial and human resources. The need for building civic institutions is so great that information professionals are just one of many voices calling out. Although economic development goals receives the attention of numerous powerful international agencies, such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund, the information situation does not have such impor-tant advocates.

Industrialized countries that are information based and information dependent are able to fully take advantage of the possibilities information technology has to offer. Countries like Paraguay have not yet realized the importance of informa-tion in national development. What is needed is a change in the attitude toward information. Changing deep cultural perceptions is not done easily. What must be done is a search for stakeholders within a country who are information literate and savvy, who have international experience and outlook, and who then work with them in designing change strategies.

A successful strategy already in place are the ongoing efforts of Ching-chih Chen in organizing conferences all over the world on New Information Tech-nology. Her effort does several things: First, by sponsoring conferences in dif-ferent countries and continents, knowledge transfer is enhanced through discus-sions, debates, and publications. Second, and equally important to the diffusion of knowledge is that these conferences create a network of information profes-sionals with similar concerns. It is this network that has the potential of becom-ing a powerful voice in bringing together the developed and developing countries to cooperatively build the global information network. This raises a third oppor-tunity for a dialog among this network of information professionals with policy-makers to share our vision of a networked world with their vision of economic cooperation and global trade. Who knows? This synergy just might move us forward toward a gentler more harmonious world. I do think the key to that lies in the diffusion of knowledge!

REFERNCES

Achleitner, H.K., & Alvaro, C. (1994). Charting the information dissemination systems in Paraguay: Opportunities for the information industry. Microcom-puters for Information Management, 11 (2), 111-120.

Backer, T. E. (1991). Knowledge utilization: The third wave. Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization, 12 (3), 225-240.

Chen, C. C. (1994). Editorial. Microcomputers for Information Management, 11 (2), 67.

Hurrell, A. (1994). Regionalism in the Americas. In A. F. Lowenthal & G. F. Treverton (Eds.) Latin America in a New World. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Klein, S. & Gwaltney, M. K. (1991). Charting the education dissemination system: Where we are and where we go from here. Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization, 12 (3), 241-265.

Lau, J. (1994). Information networking in Latin America: Promises and challenges. In 1993 State-of-the Art Institute Latin America the Emerging Information Power. Washington, DC: Special Library Association.

Lucier, R. E. (1990). Knowledge management: Refining roles in scientific communication. EDUCOM Review, 25 (3), 21-27.

Naisbitt, J. (1994). Global Paradox. New York: Avon Books.

Nelson, S. D. (1981) Knowledge creation: An overview. In R. F. Rich (Ed.), The knowledge Cycle. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Tapscott, D. & Coston, A. (1993).

Paradigm Shift: The New Promise of Information Technology. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

DISCUSSIONS

[Ching-chih Chen]

Thank you very much, Herb. Instead of having questions asked of Herb, and because our next paper from Mariano Maura is also related to the Latin American region, I would like to ask if we can hold questions and comments until the end of that paper, since some of Mariano's paper may have similar complimentary points. Mariano Maura is the Director of the Graduate School of Library and Information Science of the University of Puerto Rico. He also served as an essential member of the Local Committee of NIT '93 in Puerto Rico with Annie Thompson as Chair. He has a lot of experience with Latin America, specifically in the Caribbean region. So, his paper deals with that geographical area. Mariano, the floor is yours.

[Mariano Maura]

Thank you very much, Ching-chih, for

this opportunity, and especially for allowing me to share with this wonderful

group of people. My warmest greetings. Coming from a Caribbean guy, I really

mean it.