PANEL ON INFORMATION INFRASTRUCTURE - INTERNATIONAL SCENE

The Information

Infrastructure of Russia: Sci-Tech Information Area.

The Past, Present, and Prospects

Yakov Shraiberg

Deputy Director

Russian National Public Library for Science and

Technology

Moscow, Russia

shra@gpntb.msk.su

INTRODUCTION

Informatization in the global sense and in individual countries is determined not only by a degree of computerization and the development of telecommunication technologies that should be adequately supported legally, economically, technologically, and socially. It is determined also by the information policy pursued by the world community and an individual country.

Though private business is rapidly penetrating into the economy of the Eastern European countries, the information policy still remains there, and should remain, a prerogative of the state. Economically developed Western countries represent a good example in this respect. Though private business has long gained strong grounds in the economy of these countries, the information policy conducted on the state level prevails over other levels, that is, branch, regional, private, and individual.

A correct information policy is essential for the countries that have taken a new economic path. As Russia is one of them, we consider the outlining of the information policy as a condition for overcoming the present crisis and reaching the historical targets (Rakitov, 1994).

In this article, we are not setting the task of featuring all issues of information policy and activity in Russia. The task would be too enormous both for this article and for our professional qualification. Nevertheless, we shall examine the state-of-the-art in sci-tech information (STI), that has become one of the major branches, if not the major one, of the information policy, information activity, and informatization of the country. The analysis of the present situation and prospects of STI in Russia will allow us to estimate some global problems and decide, which type of global information infrastructure (GII) can be considered the most suitable for Russia and what measures should be taken to reach it.

A SURVEY OF THE STATE STI SYSTEM IN SOVIET RUSSIA

The present STI infrastructure and activity in Russia are inseparable from the background. We shall give a brief survey of the organization of the STI system in the former USSR.

Scientific and technological progress, and a dramatic growth of sci-tech infor-mation flows in the 50-60s forced the government of the USSR to take some administrative decisions and organizational steps. In the end of the 60s and the beginning of the 70s, the government worked out a concept of the State STI System. It outlined the development of the country in the area of sci-tech infor-mation and was based on strict state planning, regulation, and centralization.

In the beginning of the 60s, the USSR had a network of information centers that combined 4 Union, 12 republican, 30 central branch, 24 interbranch regional, and 4,000 institutional and corporate sci-tech departments. The branch had over 50,000 information specialists.

It was in those years that important decrees were issued in order to introduce certain measures and decisions. They served as a basis for the establishment of reference information collections and obligatory UDC indexing of all publica-tions; the formulation of the basic principles for the State STI System; the deve-lopment of the standard statutes for all information centers that resolved the general organizational problems of all information centers of the country and unified their activity; the unification of sci-tech information centers and sci-tech libraries of the country and the involvement of the latter into the STI System; the development of the State Automated Sci-Tech System that utilized a network of the automated sci-tech information centers, services for the distribution of infor-mation on magnetic tapes, and a distributed data bank.

In the following decade the government formulated the task of information support to the target programs. It had to resolve the vital sci-tech problems listed in the subject plan of the economic and social development of the USSR.

The goal of the State STI System was to accelerate sci-tech development of the national economy by providing the governmental bodies, organizations, and enterprises with relevant information on the latest developments in science and technology (The USSR State Committee for Science and Technology 1987).

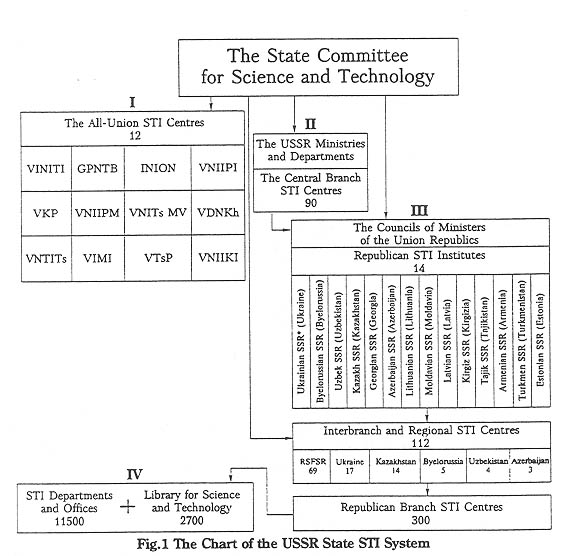

Structurally and functionally the State STI System was based on the correla-tion of the management and information levels (Figure 1).

The State STI System had a hierarchic four-level structure, every level of which had its special functions:

• The second level comprised 90 central branch information centers subor-dinate to the Ministries and Departments, and different by their subject scope. These information centers acquired information flows processed on the first level and continued their analytical processing. It is of interest, that, besides these functions, several information centers of this level undertook some Union functions. VNIINS, for instance, that is the All-Union Scientific and Research Institute of Information on Civil Engineering and Architecture, produced abstract journals on its subject scope. They existed along with the abstract journals produced by VINITI.

• The third level was represented by interbranch and regional STI centers. It included 14 republican STI institutes of the state level (Russia is not men-tioned here as it had the information structure similar to that of the USSR), 112 interbranch and regional STI centers and nearly 300 branch information centers of the local republican status that were subordinate to the Ministries of the republics. This level had to form the upward flow of information on the achievements and experience gained in the republics and regions, and provide information support to the scientific and technological programs, to the Party and Soviet organizations.

• The fourth level comprised 11,500 information departments and offices, and 2,700 scientific and technical libraries of enterprises, research institutes, universities, and design offices. More often than not, the libraries played a secondary role relative to that of the information centers, the functions of which they duplicated. The main task of this level was to provide informa-tion support to the scientists and staff members of the respective institutes, and to submit efficient and regular reports to the above levels on new technologies, products, and developments.

Despite the obvious drawbacks of the strict centralization, the State STI Sys-tem had a lot of advantages. Thus, it was easy to implement the principles of the obligatory delivery and receipt of the information, of the responsibility for the information delivered, and others. They were supported legally by special governmental decrees.

The State STI System virtually determined the information infrastructure in the area of science, technology, and social information in the former USSR (Kedrovskii, 1993). Information service of defense branches (with VIMI only partially covering the demand), statistical, legal, and administrative information were the only ones left beyond the framework of the State STI System.

Strict administrative control together with the control of the Party, that pro-hibited the introduction of market mechanisms, promoted the monopolization in the information area and excluded independent information expertise. As the country continued to develop technologically, the dictatorship of the state and strict administering started to block the path of the evolution in the information area. The situation was aggravated by the development of computers and their application for information processing.

Despite the aforementioned achievements, the State Automated STI System remained rather a declaration than a result. Only a few technologies of the first level were automated. A low quality of the telephone channels and inaccessible radio and satellite communications did not allow the State STI System to imple-ment the telecommunication access and start information exchange even on the middle level. Not a single fully automated network was introduced. Vast amounts of money spent on powerful mainframes and complicated teleprocessors were virtually wasted because a reliable access to electronic information banks was impossible. Several major state network projects, together with the noto-rious Akademset' project, turned out a failure. Telecommunication access to foreign data banks and information networks could be provided only via VNIIPAS, the state monopolist, while the quality of the channels remained poor and the service of the technologies - outdated.

It explains, why the State STI System was unable to implement information superhighway, to say nothing of the global one. However, if we were ready to divide the information and technological parts, ignore the means of information collection, processing, and transmission, close our eyes to the administrative and uncontrollable character of information cooperation and a superhighway of the state level, we could describe the State STI System as a Soviet analog of the information highway.

We can examine the State STI System in this way in the given context, be-cause, with a lot of restrictions, it was capable of providing information, indica-ting its holder, and answering information demands of the users living on a vast territory of a state with an extremely inflated administration, strictly regulated economy, ideological pressure, totalitarian policy, and specific national features of the inhabitants.

Among other factors hindering today the development of the superhighway are the following ones (The Centre of Scientific Research and Statistics, 1993):

• A low speed of information promotion. From one to three years could pass from the moment of writing to the publication of a scientific paper. The information became outdated before it was available to the general public. Publications that appeared in the regional scientific journals were, as a rule, not only outdated, in the applied sciences particularly, but also substandard, because their authors did not have access to the advanced foreign develop-ments.

• The absence of a perspective publishing program and modern polygraphic facilities. The number of scientific books and journals published in the USSR was by an order of magnitude lower than that in the United States. Only 10% of the papers written by Soviet scientists could see the light.

The STI Infrastructure in the Transition Period

The well-known political events of the beginning of the 90s led to the disintegra-tion of the USSR, the formation of new independent states out of the former USSR republics and caused dramatic changes in the economic relations.

All newly formed countries began their movement to the market economy along the same road, though from different starting points and using different techniques. On the way to it they had to learn in practice the earlier unknown liberalization of prices, freedom of trade, private business, and other notions accompanied by features inherent of the transition period from the totalitarian-communist regime to the market economy: inflation and hyperinflation, unem-ployment, falling production rates, and the reduction of living standards.

Though it is clear that these things are temporary, inevitable on the way to the civilized economy, and characteristic of the transition period through which Russia is now surviving, it worth noting that these processes are going much har-der in Russia and other Former Soviet Union (FSU) republics than in the Eastern European countries of the former socialist camp.

Reliable economic and technological cooperation was stopped, the links in the "supplier - user" chain were broken and lost, financial reserves vanished into thin air, and a unified information space ceased to exist.

The State STI System virtually collapsed on the threshold of the drastic chan-ges that were to turn it into a unified information superhighway on the basis of the already adopted conceptual and strategic documents (Tereshchenko, 1990; "The concept of development of the state STI system in 1991-1995," 1990).

The disintegration of the USSR resulted in a collapse of the legal system of sci-tech information, as it was based on the state laws and decrees adopted by the central administrative bodies. These documents had the power of the law and were rigorously followed by all information centers, and with a rather good result. It was not without reason that some American specialists compared the establishment of the State STI System with a launching of the first Soviet sputnik.

The consequences of the disintegration in the state regulation of the informa-tion area may be illustrated by several examples.

Acquisition of foreign sci-tech publications and user demand

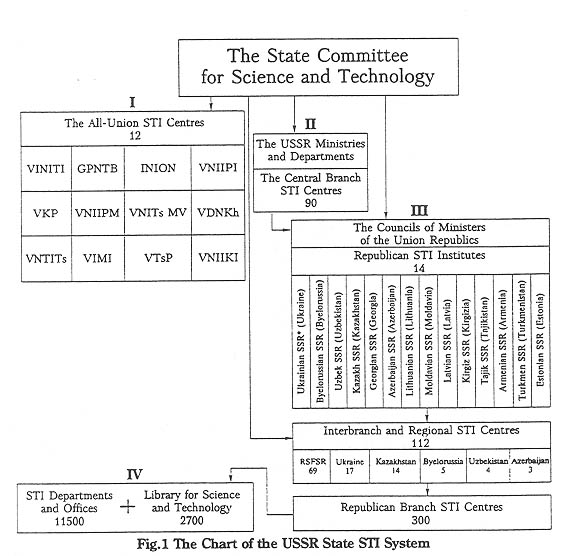

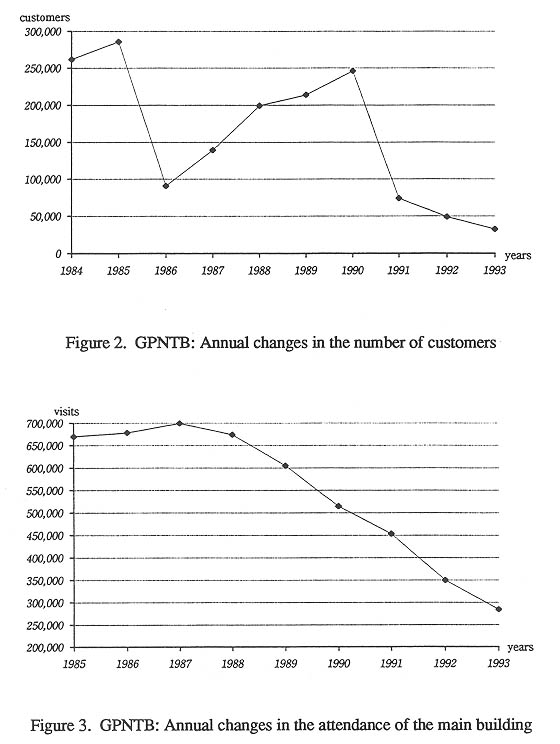

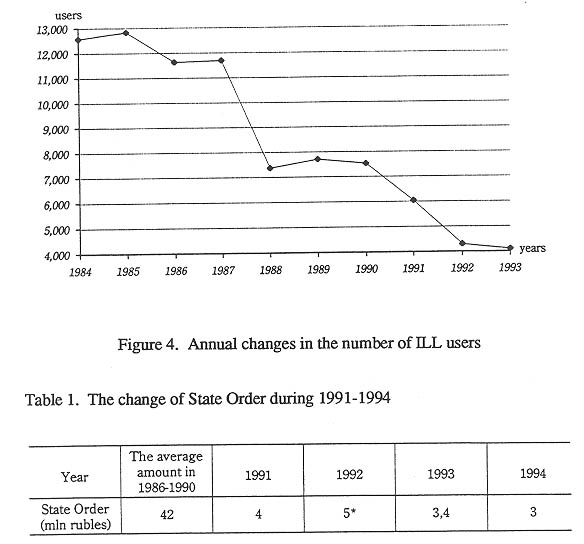

Until 1990 the government gave annually over 20 million US dollars for the acquisition of foreign sci-tech publications. Eighty percent of this amount were given to the libraries, institutes and STI System centers. The annual amount received by GPNTB was 2 1/2 million US dollars. Since 1991 until now the government has not given a single dollar for this purpose, and the libraries' and institutes' collections have been completed by foreign publications received via book exchange and random grants. As a result, we have less than 7,000 titles of foreign sci-tech journals per year, and many of them are not generally accessible as, purchased on private, not federal, money, they may be used only as their owner decides. Compare these figures with over 25,000 titles received by Russia annually before 1991 (even this number hardly covered 30% of the global flow). Many information, serial, and reference publications and monographs ceased to arrive in Russia. It resulted in an abrupt reduction in library attendance and lesser interest in the original publications. Compare the situation in GPNTB, the major scientific and technical library of the country and one of the main bodies of the State STI System. The number of customers attending the library annually (ILL and remote users are not taken into account) decreased from 262,000 in 1984 to 32,000 in 1993 (Figure 2). The number of customers attending the main building of the library fell from 670,000 in 1985 to 284,000 in 1993 (Figure 3) and the number of ILL users decreased from 12,574 in 1984 to 4,100 in 1993 (Figure 4).

Budgetary funding of scientific and information activity in the country

While the funding of science has significantly reduced and science in Russia has been suffering through hard times since 1991, the funding of the information area has reduced still more drastically. In 1986-1990 the average annual amount allo-cated to the information bodies of Russia made nearly 42 million rubles within the State STI System (it was the so-called State Order), without the money allocated by a parent organization. The situation in the following years is illustrated in Table 1.

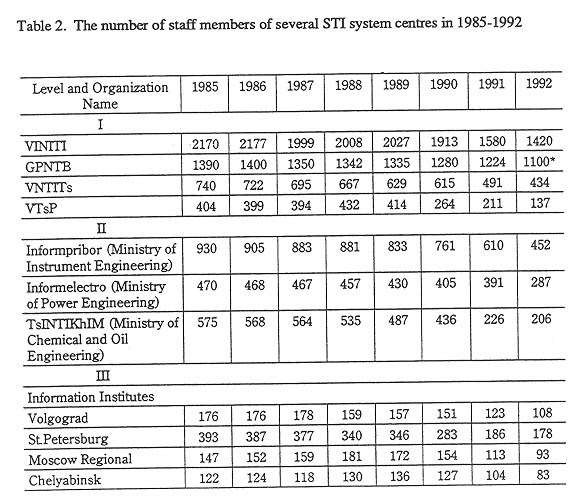

Moreover, the number of the organizations financed by the government reduced from 121 in 1990 to 57 in 1993. Most of the branch systems ceased to receive money from their parent ministries, and 7 information centers of the third and fourth levels (Figure 1) ceased to exist. Many information centers had to start a completely different business, rent premises and equipment, and fulfill commercial requests to seek jobs in other areas, which is an alarming sign in itself, minding that there was no official centralized staff reduction (Table 2).

Note that the tendency of a gradual decrease in the number of staff members is still continuing. Thus, on January 1, 1994, the Russian National Public Library for Science and Technology had 850 staff members, while this number was only 760 on November 1, 1994.

Table 2. The number of staff members of several STI system centres in 1985-1992

The formation of the Russian domestic documentary information resource

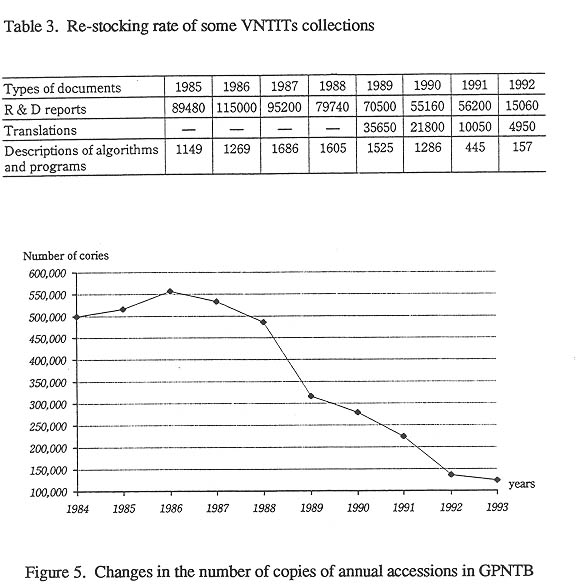

The situation here is similar to the one in the acquisition of foreign publications due to the reduced budgetary funding. Some additional problems also take place. For example, the decree of the USSR State Committee for Science and Techno-logy on the obligatory total state recording of the results of research and develop-ments has become invalid; it has reduced by more than one half the accessions of these materials in the central collections. The documentation on technological norms and standards, and other valuable technological documentation is no longer recorded. The Law of the USSR of the obligatory copy is ignored and many scientific publishing houses are voluntarily changing the subject scope of their publications in favor of commercially popular editions. All this has signifi-cantly influenced the completeness of information collections (Table 3 and Figure 5).

Table 3. Re-stocking rate of some VNTITs collections

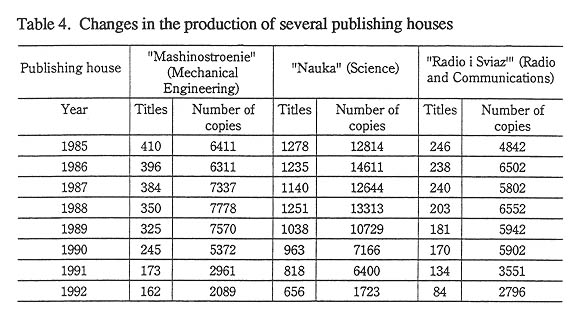

Table 4 additionally illustrates the current situation characterized by a signi-ficantly reducing number of sci-tech publications. It gives information about the three large publishing houses of Russia.

The results of 1993-1994 are still more depressing. Scientific papers were published in 200 or 300 copies only, and all sci-tech publications will soon be classified as "grey". The information represented in Tables 2-4 was taken from the Centre of Scientific Research and Statistics' data (The Centre of Scientific Research and Statistics, 1993).

In the current transition period, the lack of information and the absence of the required state support exclude the idea of the development or improvement of information superhighway or a domestic highway. This system should be created anew, on the basis of the experience and new possibilities offered by the demo-

cratization of the society, social and economic reforms. Many obstacles have been removed that stood formerly in the way of information exchange between the organizations within the country and with foreign countries. New approaches appear together with new, already implemented, projects of modern STI systems, databases and data banks, networks, and information technologies. The scope of joint projects with the Western countries is broadening and the destroyed infor-mation infrastructure of the FSU countries is under repair.

One thing is obvious. There is no more State STI System which is strictly administered and convenient for the officials (not general users). The first years in the market economy have revealed all the plagues and drawbacks in the infor-mation area. They clearly indicate the necessity of new approaches, new state programs for the creation of information infrastructure in Russia, and its inclu-sion into the global information superhighway.

Prospects of the Russian STI Resource

Considering the prospects of the Russian STI resource, we realize that a reliable legal basis is needed first and foremost to make the state responsible for the organization of the information activity and its relations with information owners. It would be naive to think that the commercialization of the society and the economy could diminish the role of the state in the information area. Even in the United States 70% of the institutes and libraries belong to the state. A law on sci-tech information is needed in which the total information activities are considered as a separate area. Ministry of Information should be established, a package of norms and decrees should be issued, and a profound expertise of the present institutes and information centers should be conducted. A new efficient structure of STI bodies should be formed that will become a basis of a new information infrastructure of Russia.

Much has been done to achieve these goals. Below we shall name the prin-cipal events:

2. Regulations have been issued for Rosinformresurs - a union responsible for the unification of Russian information resources of sci-tech develop-ment. As a state information and technological complex Rosinformresurs functions as a leading body for 69 interbranch regional centers of the third level of the former State STI System (note, that all 69 centers have sur-vived!). It is responsible for the creation and utilization of the state sci-tech resources of the whole country, the systems of the automated infor-mation processing and transmission ("Regulations of the Russian Union of Information Resources of Sci-Tech Development...," 1993).

3. A draft Federal Law on "Information, Informatization, and Information Protection" has been worked out. The Law formulates the legal basis of the formation and utilization of information resources and considers the growing importance of information for the renovation of the production, organizational, and managerial potential of the country, and inclusion of Russia into the world community ("A Draft Law of the Russian Federation 'On Information, Informatization, and Information Protection', " 1992).

4. A Decree on "The Basics of the State Policy in Informatization" has been issued by the President of the Russian Federation. The Decree stipulates the establishment of a committee for the informatization policy that will be subordinate to the president. It is to coordinate the implementation of the information policy by the state bodies.

5. A package of laws, norms, legal acts and organizational documents has been adopted to improve the legal basis of information activity. Among them are the Law on "The Legal Protection of Computer Programs and Databases," "The Patent Law of the Russian Federation," "The Law on Mass Media," a draft Law "On the State Policy in Science and Techno-logy," an agreement "On the Interstate Exchange of Scientific and Techni-cal Information," a Decree "On the State Expertise in Science," and others (over 50 documents were adopted in the past two years).

The next significant step to be taken for the formation of a new information resource of Russia is a development and implementation of federal programs with a long-term state funding. One of the achievements in this field was the State Scientific and Technical Program of Russia entitled "The Federal Informa-tion Resource of Science and Technology" and adopted in 1993. The program neither envisages the reanimation of the State STI System nor creates a strict organizational structure. Its main idea is to coordinate and stimulate information centers, institutes, and libraries of Russia engaged in the creation of the state sci-tech collections and provision of an efficient access to the information by means of modern information technologies (Gubanov, 1993). Over 150 research institutes and information centers together with the Academy of Sciences are involved in this program. The program has 10 main sections and 140 projects designed until the year of 2000. Section 1, for instance, named "Acquisition of the State Sci-Tech Collections of the Public Access," includes 9 projects, among which is "A System of Interbranch Coordination of the Acquisition of the State Collections of Foreign Sci-Tech Publications," the leading body in which is GPNTB. Section 3 entitled "The Formation and Utilization of Databases and Data Banks of Sci-Tech Information" includes 69 projects of databases, including the project named "The Development of the Federal Data Bank of Domestic and Foreign Publications on Natural Sciences and Technology." The organization responsible is VINITI.

The projects were selected on a competitive basis and the general supervision and funding of the program is done by the Ministry of Science and Technological Policy of the Russian Federation that is a successor of the former USSR State Committee for Science and Technology, but has lesser centralized and directive functions.

Besides this program, the Ministry maintains several other programs related to the information area. This is, for instance, a program of R & D computerization. Several other programs have been developed and funded by other organizations, including the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Ministry of Higher Education, the Ministry of Public Health, and the Ministry of Culture.

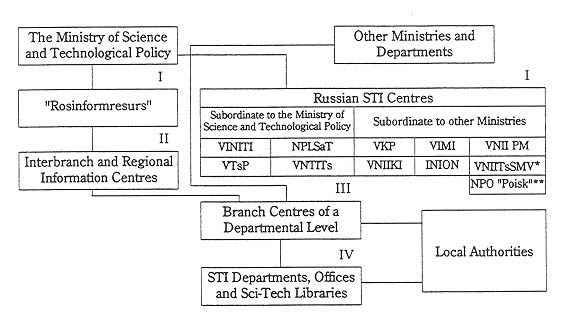

Compared with the organizational and functional structure of the former State STI System, the present STI System of Russia has undergone changes. Informa-tion centers of the republics have quitted the System, the number of the second-level centers has naturally reduced (we have less than 30 of them today), and the number of the first-level centers has reduced by one (the total number is 11). The administrative system has also drastically changed: the Ministry of Science and Technological Policy no longer administers other ministries and information centers, but cooperates with them within the framework of long-term programs. The chart of the present STI System is represented on Figure 6.

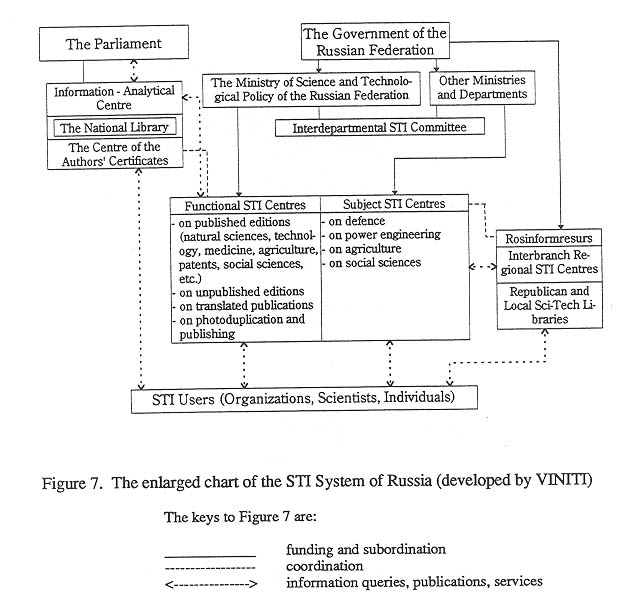

The given chart is undoubtedly far from perfect, but at present, when the formation of legal foundations has not yet been completed and new economic conditions are coming into force, it may serve as a stimulus for the improvement of the activity of sci-tech centers as part of the total information infrastructure of Russia. Several new charts have already been proposed. The one developed by VINITI is represented on Figure 7.

Figure 6. The chart of the present STI System of Russia

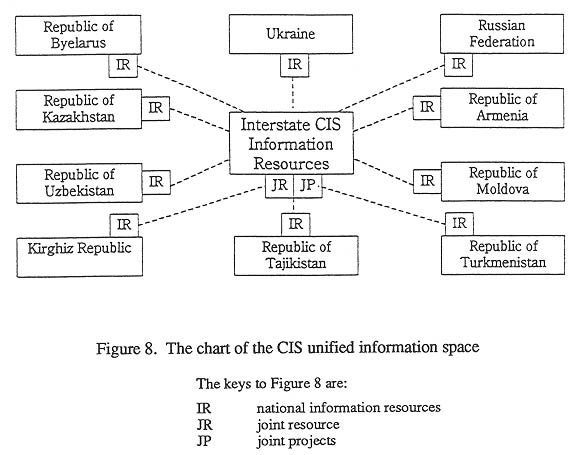

Still another significant factor is a formation of a unified information space of the CIS countries. It is a system of national information resources coordinated organizationally and methodologically in time and space, and a system of the interstate information resources meant for the implementation of joint programs and managerial tasks on the interstate level (Belov, 1993). Several interstate commissions and councils have been set up and set to work. Among them is the Interstate Coordination Council on Sci-Tech Information responsible for several joint projects signed by information centers of the CIS countries.

The chart of the unified information space is represented on Figure 8.

The CIS unified information space include Republic of Byelarus, Republic of Kazakhstan, Republic of Uzbekistan, Kirghiz Republic, Ukraine, Interstate CIS Information Resources, Republic of Tajikistan, Russian Federation, Republic of Armenia, Republic of Moldova, Republic of Turkmenistan

Information activity of sci-tech information centers of Russia within the projects of the CIS unified information space is the first step on the way to the European and, later, to the world information space. In other words, it is an initial step on the way to the information superhighway.

It is worth mentioning, that the role of libraries is increasing today with the development and renovation of the whole sci-tech information area. Within the State STI System in the 70s and 80s, the libraries always played a secondary role and were considered as a raw material appendage of sci-tech information centers. Regional libraries especially were given little thought and a logical program of their technological re-armament and inclusion into the information activity did not exist at all.

Today the role of libraries in the creation of the information resource of the country is generally recognized. The libraries in Russia, holding millions of items of sci-tech publications, start to function as information centers and possess their own federal resources that are an integral part of the state information resource. As an example, we can speak about the systems of the Union Catalog and, particularly, about the computerized Union Catalog of Sci-Tech Publica-tions. It has been maintained by the Russian National Public Library for Science and Technology and has over 700,000 bibliographic records reflecting the acces-sions of 400 Russian libraries (formerly the Catalog reflected the accessions of over 1,000 libraries of the USSR). Besides, the libraries cooperate via ILL, there is a system of the National Bibliography maintained by the Russian Book Cham-ber, and a number of systems are under way for the coordination of acquisition and book exchange.

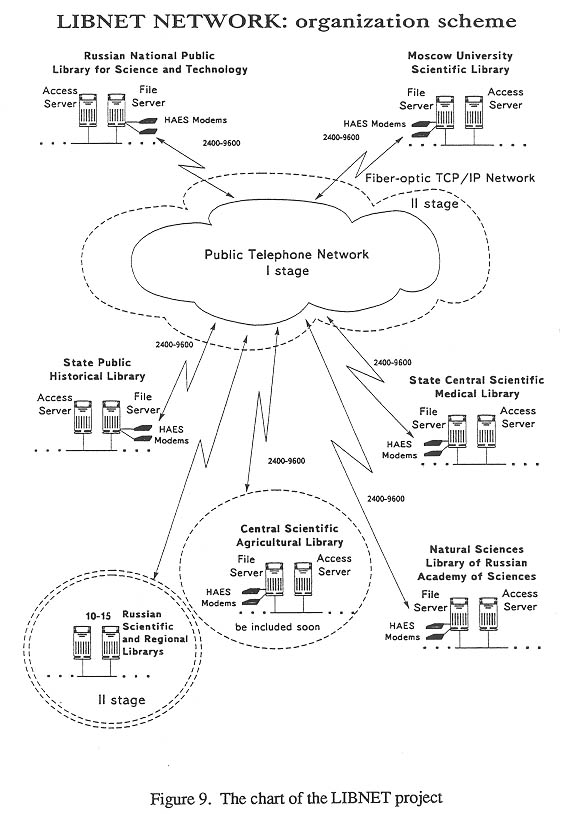

Most of the Russian libraries use INTERNET (the Russian part of which is called RELCOM) and modern telecommunication technologies become popular. Among the latter are a LIBNET project for the network of the major Moscow libraries (see Figure 9) and other projects (Shraiberg, 1993)

Library systems and networks, regardless scientific and technical, universal, medical, agricultural, regional, and others, effectively supplement information resources of the country on the way to the unified superhighway.

In addition to the aforementioned facts and developments, some other pro-grams that are planned for implementation in the near future should be men-tioned. These are:

• Integration of information collections and creation of the systems for a unified access to the databases and data banks of sci-tech publications, as there are over 20,000 databases in the country today.

• Attraction of additional funds for the development of the STI system, in-cluding private funds and international projects.

• Improvement of the analytical work and research in the area of STI and expertise.

• Enhancement of library automation and introduction of telecommunication technologies, access to the domestic and world information resources, development of multimedia and artificial intelligence systems.

• Complete transition to the international standards

and formats and adhe-rence to the principle of the general availability

of publications.

Conclusion

A construction and development of the information infrastructure of Russia, as well as its entry to the information superhighway require profound research and a special program. The advanced foreign experience should be taken into consi-deration, Russian and foreign professionals should be invited, and the job should be done in accordance with the unified national information policy.

Information infrastructure should be flexible and

easily adjusted to the chang-ing economic situation. It should be based

on modern information and computer

technologies, networks, and communications to ensure effectively and reliably one of the basic human rights - a right for information.

Let us presume that the first step has been taken, while the following ones stand out clearly in the distant prospects.

REFERENCES

"The Concept of the Development of the State STI System in 1991-1995." (1990). Scientific and Technical Information, Series 1, No. 9, pp.9-15.

The Center of Scientific Research and Statistics, Moscow. (1993). Science in Russia: Collection of Statistics. pp.251-267.

Development of the State Policy in the Formation and Utilization of the Infor-mation Resources and a Program of the STI System Modernization. (1992). Scientific and Technical Information, Series 1, No.9, pp.9-21.

A Draft Law of the Russian Federation "On Information, Informatization, and Information Protection. (1992) Russian Information Resources, 5-6, 2-10.

Gubanov V.A. (1992). On the National Information Policy: Aspects of the Scientific and Technical Information. Scientific and Technical Information, Series 1, Nos.3-4, pp.17-19.

Gubanov V.A. (1993) The State Information Policy of Russia: The State Infor-mation Resource Program. Russian Information Resources, 4, 7-9.

Kedrovskii O.V. (1993). We Know Not What Is Good Until We Have Lost It. Russian Information Resources, 5, 2-4.

The Law of the Russian Federation "On the State STI System of Russia" (draft). (1992). Scientific and Technical Information, Series 1, No.1, pp.3-5

Rakitov A.I. (1994). Russia in the Global Information Process and Regional Information Policy. Introduction to Information Technology and Information Policy. INION RAS, pp. 5-25.

Regulations of the Russian Union of Information Resources of Sci-Tech Develop-ment Subordinate to the Council of Ministers - the Government of the Russian Federation (1993). Russian Information Resources, 4, 2-5.

Shraiberg Y. L. (1993). The State of Library Automation in Russia. Microcom-puters for Information Management, 10 (4): 293-310.

Tereshchenko S.S. (1990). The Strategy of the Development of the State STI and ASTI Systems in 1991-1995. Scientific and Technical Information, Series 1, No.8, pp.18-21.

The USSR State Committee for Science and Technology,.

Institute for the Advanced Education of Information Specialists, Moscow.

(1987). Organiza-tion of the Scientific and Methodological Activity:

Methodological Guide. Moscow, The Institute for the Advanced Education

of Information Specialists.

DISCUSSIONS

[David Penniman]

Thank you very much. Comments from the audience?

[Richard Quandt]

I wonder if there are funds available for acquisitions and also funds available for staff. As a result of this, is there a kind of professional staff brain drain for the libraries to the private sector or foreign countries, as been experienced by libraries in the Eastern Europe?

[Yakov Shraiberg]

I want to divide the answer to this question in two parts. For our library, we have not received any funds from outside except assistance from AAAS and some others. Now, it is only my opinion: I think that the No. 1 problem is that it is vital to have support for foreign periodicals acquisition. The second point is the necessity to use support from outside foundations for training.

[David Penniman]

You have a figure showing the drastic dropping off in customers. Do you have a similar chart showing how the number of library staff dropped off sharply?

[Yakov Shraiberg]

Yes.

[David Penniman]

In terms of lost talent, I think that was the point that Richard Quandt was driving at. Have library staff been drawn away to other parts of the market? If so, where do you get your staff trained?

[Yakov Shraiberg]

Table 2 of my paper shows the sharp drop. Most of library's capable technical staff have been drawn away by the private sector with much higher salary.

[David Penniman]

One more question.

[Elizabeth Kirk]

I just want to comment that we have visited 19 libraries in January or Fe-bruary this year. Of which one or two technically trained staff members were sponsored by the Library of Congress and IREX. Within 6 months, they were gone -- working for the private sector. I don't know how you can keep these people. Yakov's library is an exception because he has a large number of staff who are technically trained.

[David Penniman]

I hope that we will be able to come back to ask more

questions to all members of the panel. Our next speaker is Marinus Swanepoel

from the Gold Fields Technobib, Technikon, Pretoria, South Africa.