Wallace C. Koehler, Jr.

International Information Associates, Inc.

Oak Ridge, TN, USA

The University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN, USA

E-mail: willing@usit.net

Librarians and other information specialists are familiar with a wide range of print and other materials and their varying formats -- monographs, serials, pamphlets, microfilm, audio, visual, and so on. Internet material has been classified in general terms, in terms of the means of information delivery -- telnet, listserv, newsgroup, ftp, as well as gopher and html WWW pages. In general, WWW material is inadequately classified. The paper suggests three general types -- "jump," "gateway," and "content" pages. Jump pages provide hypertext links to usually related pages not a part of the same family of pages. They serve a reference function. "Gateway" pages describes the contents of subordinate pages and serve a "table of contents" function. Content pages contain actual textual, numeric, graphic, audio, or visual data. Often, Webpages are a hybrid of these three types, the most common the jump, followed by gateway and content pages.

Internet material will be written with greater frequency in indigenous languages in more developed countries because, I posit, communications are internally oriented. Because the target audience is often foreign, the more underdeveloped countries will post in English, the lingua franca of the Internet and most other international endeavors. Webpages are more content oriented in the more underdeveloped countries as a proportion of all in-country pages because the Internet is used there as a medium of communication among business, scientific, pedagogic, and government elites. As Internet access is democratized, "college sophomores" and marketers compete with "traditional Internet elites" and the number of more "trivial" and commercial sites increases as a proportion of all in-country Webpages.

The paper will focus on Internet use in Mexico and South and Central America. Spanish, Portuguese, and French are the primary indigenous languages of the region (English speaking countries are excluded). Both economic and Internet development varies widely from great sophistication in second tier countries (e.g. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico), moderate sophistication in third tier countries (e.g. Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela ). Haiti and Cuba offer other valuable lessons in Internet use.

There is a little order to the chaos of the Internet. This paper seeks to describe some of that order by exploring Latin American practice. Latin America is defined in its broadest sense to include the countries of South and Central America and the Caribbean as well as Mexico. Why Latin America? There are several reasons:

• Second, the Internet experience of these countries ranges from the very sophisticated (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico) to non-existent (Guyana, Haiti, St. Kitts, Surinam). Internet sophistication parallels economic development as well as the sophistication of other telecommunications infrastructure. The literature on the role of the Internet in development, as a tool for democratization, or as an agent in Latin America is sparse. There are a variety of factors which further influence Internet connectivity in these countries (Dias, 1994; Hollis, 1994; Ciurlizza, 1996), its use as a research resource (Resnick, 1995; Rodriguez, 1996), and which will impact further developments (Cabezas, 1995; Mansilla, 1995). There has been little effort to explain these processes.

• Third, patterns of server ownership and access vary from diverse (Costa Rica, Mexico) to limited (Brazil). In some cases, ownership is dominated by commercial entities, in others by universities or governments. Although beyond the scope of this paper, the ownership/access dimension significantly affects the type of material mounted on servers in various countries. In Brazil, with government and academic ownership, most material is of scientific or technical content. Almost anything can be found on Mexican servers. For a list of server owners world wide, see http://www.iworld.com/resources/.

• Fourth, as everywhere else, Latin American Internet servers employ functional and geographical URL domain naming standards and practices. Many also carry domain naming practices to the second-level. Use of top- and second-level domain names facilitates searching, particularly with the advent of the new search engines.

• Finally, Latin American Web documents range from the very simple to the very complex. This variation offers a test bed for development of a Web document taxonomy. Definitions and names are suggested for three types of Web documents.

I would suggest that these issues have both theoretical as well as practical implications. Not only can they contribute to our understanding of the Internet and its uses, they can also contribute to search approaches and search methodologies.

2. DOMAIN NAMES

Domain naming is addressed first because it lies at the basis of the methodology for determining Web document nationality and function. Domain names are read from right to left. They indicate the location of the computer, the host, and the server where any given Web document resides.

2.1. Top-Level Domain Names

Web documents were counted by top-level and second-level domain names in August 1996 using the HotBot Expert search engine. A total of 53.3 million documents were counted. 30.5 million used functional domain names, 22.8 million geographic. Of the 22.8 million, 12.7 million employed standard functional second-level domain names. The original top-level domains followed the US functional naming convention:

• .edu for educational institution,There are others, now used rarely. The functional naming convention is used in more than 30.5 million or 55 percent of existing Web documents. Many of these, but by no means all, have a US origin.• .com for commercial entity,

• .gov for any level of government,

• .net for network service provider,

• .org for organization, and

• .mil for military entity.

The second top-level domain naming method utilizes the two-figure ISO 3166 standard (see Country Codes from ISO 3166, http://www.lib.waterloo.ca/country_codes.html). Countries and other political divisions (Puerto Rico, Antarctica, Soviet Union, for example) are assigned a code. This code is used as the top-level domain name for most non-United States servers as well as a growing number of US servers.

The domain name lies between the first two forward slashes // and the first forward slash / of the URL. For example, the domain name in the URL cited above is www.lib.waterloo.ca. The top-level name, .ca, indicates a Canadian origin. .waterloo may indicate the city or the university in that Ontario community. Directory and file structure follow the first forward slash.

2.2. Second-Level Domain Names

World Wide Web URL domain names contain at least two domains, and frequently three or more. There are no formal standards regulating second- or subsequent level domain naming. There are three common practices. The application of these practices is governed by each server owner or the individual registry. These practices are:

• Use of second-level functional codes are limited to those Web documents using geographic top- level domain names only. There are approximately 8.8 million Web documents carrying second-level functional domain names, approximately 16.5 percent of all Web documents and 38.7 percent of those using geographic top-level names. There are two sets of functional codes now in general use, and each has a variation:

Type 1 follows the top-level functional naming convention: .com, .edu, .gov, .mil, .net, .org. The variation adopted by some Latin American countries is to substitute .gob [gobierno] for .gov [government].

Type 2 employs different abbreviations for commercial and educational: .co and .ac. The variation is to shorten .gov and .org to .go and .or.

There are also several single country practices: Egypt labels educational servers with the second- level domain name .eud, Bulgaria uses .acad. Israel employs .k12 to indicate secondary school servers. The .k12 domain name is not used as a second-level domain name elsewhere, but often occurs as a third-level domain name (e.g. k12.ca.us). A number of countries use both Type 1 and Type 2 second-level domain names.

• Geographic codes are applied. These represent approximately 1.7 percent, or almost 900,000 Web documents. This practice is most common in the United States and is reserved for those Web documents employing the geographic top-level domain nomenclature (.us). The second-level domain name attached to these Web documents are typically the postal codes for US states (.tn .us for Tennessee, .ca.us for California, etc). Some potential for confusion exists between US state postal code abbreviations and the ISO 3166 standards. For example Azerbaijan and Arizona share .az, Tunisia and Tennessee .tn, Colombia and Colorado .co, New Caledonia and North Carolina .nc, and so on.

The estimate of the number of Web documents per domain was accomplished using the WWW search engine HotBot Expert, located at http://www.hotbot.com, to generate the data. The HotBot Expert template can be divided into two sections -- search term and search parameters. HotBot Expert supports three search parameters -- date, format, and domain. If no term is provided and no parameters specified, HotBot Expert will not operate. However, if the search term is left blank, but search parameters are specified, it is possible to generate a count of all Web documents which meet the specified parameter criteria. Thus, by entering a single top-level domain name at the appropriate place, an estimate of the number of Web documents found within that domain is generated. For example, approximately 13.7 million documents carrying the .com (commercial) top-level domain name existed at the time these data were collected. Similarly, there were 73 Web documents which carried the top-level domain name .nc or New Caledonia for the same period.

The estimate of the number of non-English Web documents per top-level domain was calculated by examining the abstracts for the first 100 hits generated by a HotBot Expert search, using the domain parameter control. The percent of non-English hits is multiplied by the total number of Web documents identified in that domain. There are inherent problems with this approach:

• Second, HotBot Expert returns are relevance ranked, thus the first 100 hits should be the more relevant ones. However, using the search technique described, all returned documents are relevant if and only if they carry the appropriate top-level domain name. All examined do. HotBot consistently returned the same documents and in the same order following resubmission of the same search query. The online documentation does not explain how the selection is made. Is there, for example, a built-in bias for Web documents in a certain format, in a given language, of a certain length? This is unclear. The interpretation of the number of English or non-English Web documents found in any given domain should be tempered and qualified. However, given the large number of documents and the large number of domains searched, it is likely that any error introduced in one search will be counterbalanced by a similar but opposite error in a second search. In any event, these data should be considered indicators rather than as absolutes.

• Third, the Internet is dynamic. Any given distribution is subject to change as the Internet changes. This is particularly true of some of the smaller top-level domains. For example, "Bulgaria" (.bg) was searched during the first week of August 1996, and 2848 hits were returned. One week later Bulgaria was again searched, with a return of 3345 hits for an increase of more than 14 percent over the period.

• Fourth, and most importantly, the data for geographical domains might be interpreted to suggest the absolute number of Web documents produced and/or mounted within those geographical/political entities. No such interpretation should be taken. There is no prohibition against anyone mounting Web documents on servers using the functional top-level designation. For example, Sri Lanka source Web material can be found not only on the domain .lk," with 579 hits, but also on http://www.lanka.com (one hit) and http://www.lanka.net (2285 hits). No Web documents were found for many countries and other entities when searching by the ISO 3166 top-level domain name. Searches on the domain names for Guyana (.gy) and Surinam (.sr) yielded no hits in August 1996, but limited material can be found at http://www.guyana. com, http://www.sr.com, and http://www.surinam.com.

"Web document" is a term used loosely by HotBot. The construct of Web documents is considered in the section entitled "Web taxonomy." The Web documents generated by a HotBot search include both subordinate and superordinate pages, each a part of what I define as a consanguineous gateway. That may result in over counting and is analogous to counting separate book chapters and possibly even pages as independent intellectual contributions. With that understanding, in August 1996, HotBot Expert provided an estimate of more than 53.3 million Web documents, mounted on more than 9.4 million hosts, or approximately 5.7 Web documents per host.

4. WEB TAXONOMY

4.1. Hierarchy

A number of terms have been suggested to describe the presentation, the form of material found on the World Wide Web. These terms include "Webpage, " "Web document," "Web site," node," and "family of Webpages or Web documents." Users tend to use these terms loosely or interchangeably. The taxonomy of the World Wide Web is complex, and these terms might better be used to describe different aspects of that taxonomy. Each of these terms is useful and should be retained in the descriptive lexicon.

Webpages can be defined as the contents of a single screen. A single screen is not limited to the monitor display, but may consist of extensive scrolling. All material is contained within the page. No hypertext or other links are required to access the information provided.

Web documents are a collection of one or more interrelated, associated, integrated Webpages. Each Webpage is an integral part of the whole Web document, just as sections or chapters are integral components of articles or books. Each Webpage is a Web document, but each Web document consists of one or more Webpages.

Web document families vary from very simple constructs to the very complex. The term "family" has frequently been used to describe the relationship among related Web documents. This application of the term is a useful metaphor. The relationship, the linkages among Web documents bears an interesting similarity to genealogical tables. Because of that similarity, genealogical terms, I suggest, might prove useful in describing Webpage relationships. Just as the point of departure in genealogical description is the individual, so it is in describing Webpage structures. In describing a genealogy, a target individual, a propositus, is required. Similarly, a propositus page (sometimes termed "root document") must be identified before the relationship among Webpages and Web documents can be described. The propositus page is frequently the homepage of a Web document, but it need not be. The propositus page may be a superordinate or subordinate page to a homepage. Consider, for example, the homepage for the renewable energy program at the US Department of Energy (http://www.eren.doe.gov). The page provides two links to superordinate pages: the Department of Energy homepage (http://www.doe.gov) and the White House homepage (http://www.whitehouse.gov). Both links from the renewable energy program page are direct. Three steps are required to move from the Department of Energy The EREN homepage also provides links to consanguineous subordinate pages, that is pages located within the same directory on the same server. The concept is discussed below. The subordinate pages are homepages, propositus pages perhaps, for the various offices and programs within the renewable energy division. These pages, in turn, link to both consanguineous and adoptive subordinate pages. The adoptive subordinate pages describe various renewable energy programs at various institutions around the world. Most of these Webpages are homepages (and depending on perspective, propositus pages) capping a wide variety of Web documents.

Another highly complex Web document is Peru's homepage (http://apu.rcp.net.pe). The homepage points to an "index page," which in turn points to ten subordinate Web documents. Each of these serves as a homepage and index to additional pages. For example, the "Sector Gobiernal" (http://apu.rcp.net.pe/rcp /rcp-gob.html) links to twenty-four government branches, ministries, and agencies. These, in turn, point to further subdivisions, and finally to "data." For example, the Ministry of Agriculture homepage (http://www.minag.gob.pe) points to an index, which in turn points to an index of agricultural statistics (the URL is http://www.minag.gob.pe/MINAG/estadistica/estadistica.html). This points to an index of prices http://www.minag.gob.pe/MINAG/estadistica/precios/precisos.html). This, in turn, leads to content: a list of fruit prices in Peru's principle markets for a six month period (http://www.minag.gob.pe/MINAG /estadistica/precios/C-58C.html).

Under the terminology proposed here, the Ministry of Agriculture Web document is an adoptive part of the Peruvian government Web document, since servers change. The subordinate Webpages within the Ministry of Agriculture Web document are consanguineous. Therefore, Webpages may be related to one another in two ways: through file and subfile structure and through hypertext linkages. Consanguineous Webpages are related through file structure where one is created and stored on the server as a subfile of the other. Webpages related through file structure may be but need not necessarily be linked directly or indirectly to one another.

4.2. Structure

Web documents can be divided into at least three types or groups: "Gateway," "jump," and "content." The determination of Web document structure is less concerned with the file or hypertext connection among individual Webpages, but more with the overall or coherent purpose of the document. A distinction is made however, between "consanguineous" and "adoptive" gateways based on their file and hypertext structures.

• Gateway Documents

Gateway Web documents consist of related documents and pages combined as a unit or as a whole. The homepage or index page provides table-of -contents like direction to the content of the entire Web document. It is in effect a gateway to document content. Consanguineous gateways consist largely of file related documents, while adoptive gateways incorporate Web documents located elsewhere on other servers into the coherent whole. The Peruvian Web document (http://apu.rcp.net.pe) described above consists largely of subordinate pages located on the same server and in the same file structure. It is therefore an example of a consanguineous Web document, even though an important portion of the document is adoptive.

The US Department of Energy Renewable Energy Web document is adoptive (http://www.eren.doe.gov). The first two and sometimes three levels of the document are largely consanguineous, but the general structure and design of the document is adoptive. Independent Web documents are incorporated through hypertext links (and not through file structure) into the whole of the renewable energy document. These documents are selected and categorized according to the information (content) they provide.

• Jump Documents

Jump documents are almost always adoptive in form. While there may be a common theme underlying a Web jump document (e.g., European tourism), no effort is made to bring the document into a coherent single whole. A jump document resembles more a directory rather than a table-of- contents that the gateway emulates. Jump documents generally lack superordinate-subordinate structure. They also lack the internal structure exhibited by gateways and tend to be more random in their organization. A good example of a jump document is the EcuaNet document (http://www3.ecua.net.ec). The homepage points to a diverse set of consanguineous and adoptive documents, including advertising. If, for example, the organizations link were followed (http://www3.ecua.net.ec/organismos), a diverse collection of political and private institution homepages would be provided. The Web document is useful and graphically rich. With the exception that most of the material addresses Ecuadorian themes, the document lacks coherence. This is not a criticism. Jump documents, by definition, lack coherence.

• Content Documents

Both jump and gateway documents can provide substantial substantive information, but their primary purpose is to provide direction within the document whole. Content documents, on the other hand, provide textual, numeric, graphic, audio, and or video data. Content pages are usually subordinate to gateways or jump pages, but may stand alone. The Peruvian fruit price page cited above is an example of a content page subordinate to a series of gateways (http://www.minag.gob.pe/ MINAG/estadistica/precios/C-58C.html).

The Content+1 page is a variant of the gateway. It is the Webpage which lies immediately above content pages. The content+1 page describes, points to actual content, and is often the first place that actual content is referenced in detail. It is not uncommon to access the homepage of a complex Web document and be provided few if any clues to the data content of the document. It is too often necessary to click down, to peel away the layers within the document to identify and access that information.

5. LANGUAGES OF THE LATIN AMERICAN WWW

The number of Latin American Web documents represents a relatively small proportion of all Web documents. Based on the August 1996 HotBot search described above, the largest block of documents are those carrying functional top-level domain names: 30.6 million of the 53.3 million total. Most of these, but not all originate in the United States. North America (less Mexico) represents by far the largest block of Web material (nearly 63 percent), followed by Western Europe (22 percent) and Asia (8 percent). Latin America, with its nearly 700,000 Web documents, represents only 1.3 percent of all Web documents.

Nearly 80 percent of all Web documents are published in English or have English language mirror pages. This is no surprise since English is the language used by the major Web document publishers: the United States (73 percent), the United Kingdom (4.3 percent), Canada (3.6 percent), Hong Kong (2.4 percent), Australia (2.3 percent), India (0.4 percent) and South Africa (0.3 percent).

If documents published in English in these countries (86 percent of the total) are eliminated, language distribution in Web documents is reversed: English 30 percent and Other Languages 70 percent in the remaining 14 percent of Web documents. If indeed the number of Web documents being produced in non-English speaking countries is growing exponentially, while the number in the United States is growing arithmetically, the dominance of English on the Web will wane.

There is also an interesting regional distribution. Almost all Web documents published in Africa, North America, the Pacific, and South Asia are published in English. On the other hand, more than 70 percent of Asian documents, 60 percent of Western European documents, and 38 percent of Eastern European documents are in languages other than English. The same pattern is true in Latin America as well: South America 86 percent, Mexico 74 percent, Central America 70 percent, and the Caribbean 19 percent. The Caribbean, it should be noted, contains numerous anglophone countries.

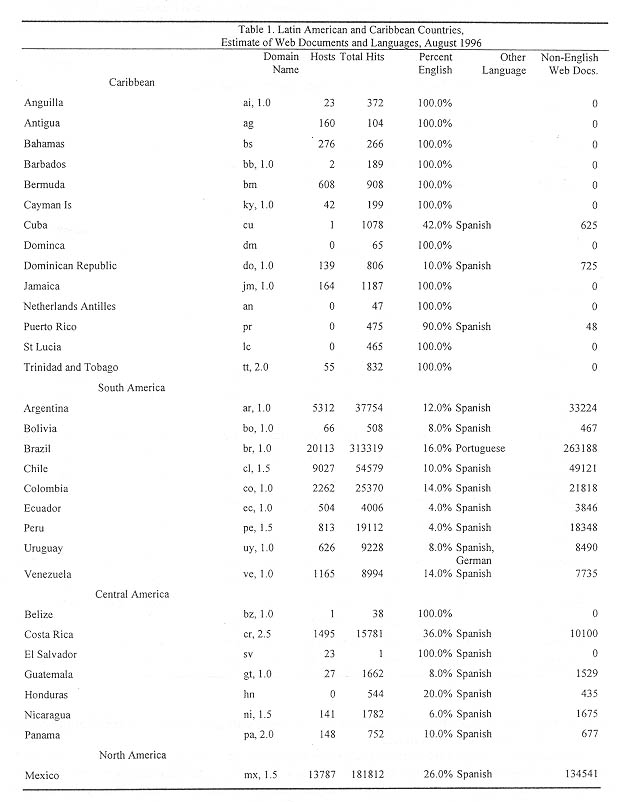

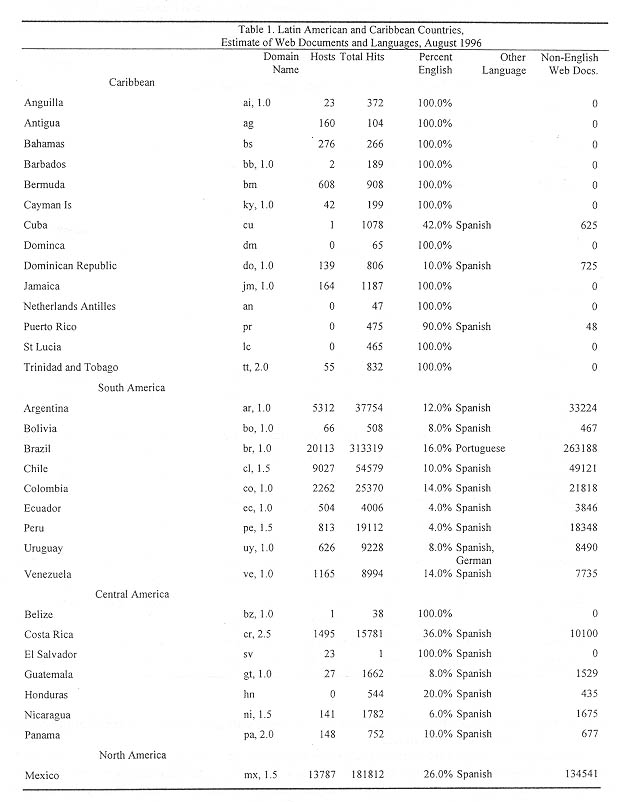

Table 1 provides data on countries using the ISO 3166 top-level domain standard and furnishes greater detail on the distribution of hits by languages. The information included in Table 1 are:

• The second column (domain name) provides the ISO 3166 abbreviation as well as the type of second-level domain name practice.

• The third column lists the number of hosts, defined as any domain name with an IP address (http://www.nw.com/zone/WWW/defs.html), that is any computer connected to the Internet.

• The fourth column lists the total number of hits returned by the HotBot Expert searches described in the methodology section.

• The fifth column provides an estimate of the total number of pages in English.

• The sixth column lists the other language(s) found.

• The seventh column estimates the total number of non-English Web documents in the domain.

English is clearly the primary second language on the Latin American WWW. Almost none of these countries published material in languages other than its indigenous language or English. It is, in fact, striking that there are almost no Spanish language documents on Brazilian servers, and almost no Portuguese on the Spanish speaking servers. No English speaking country, including Belize where Spanish is an important second language, published material in any other language than English.

Data for several hosts are not reported in Table 1. These are servers which do not comply with the ISO 3166 naming convention. These include http://www.guyana.com, http://www.sr.com, http//:surinam .com, and others. No estimate of the number of Web documents resident on these servers has yet been generated. There are Dutch language documents on the Surinamese servers.

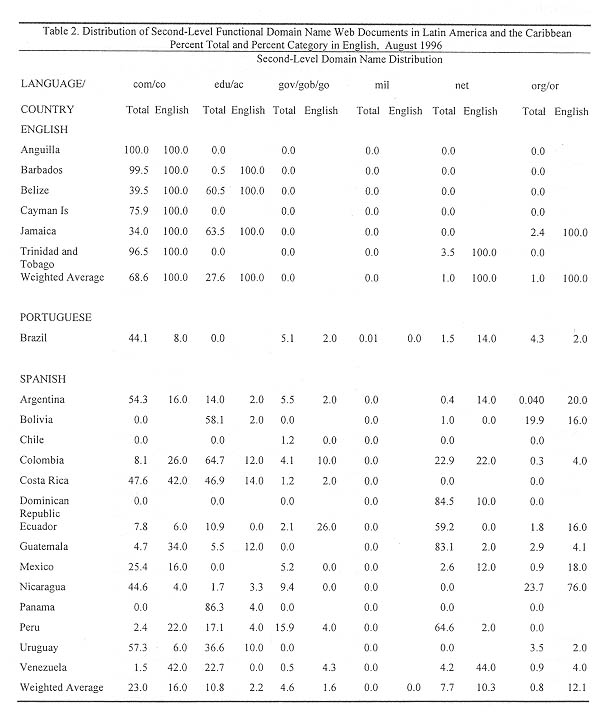

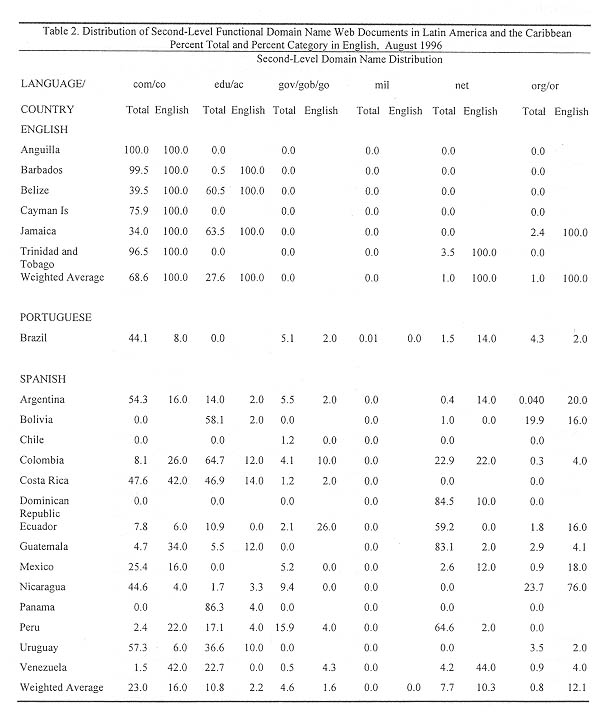

Table 2 provides the distribution of Web documents by language, broken down by second-level domain practice for those Latin American countries using them. Two columns are listed under each generic second-level tag (.com, .edu, .gov, .mil, .net, and .org). The first of these two columns gives the percent of all documents for that top-level domain (country) in each of the second-level categories. For example, 100 percent of all Anguilla (top-level) are designated as commercial (second-level). Note that these "first columns" do not necessarily add to 100

percent, since not all top-level documents in a domain carry the second-level functional tags, as is the case in the Cayman Islands.

The second column under each second-level tag reports the percent of documents in that category in English. Thus, 16 percent of Argentine commercial documents were found to be in English, while 2 percent of Uruguayan organization documents were. Weighted averages are reported for each column, giving "regional" or "language area" value for all relevant documents.

Table 2 is rich in information. It provides a distribution of Web document ownership and usage grouped by indigenous language. Almost all documents published on the small island anglophone servers are commercial or educational. Most of these commercial documents are, after inspection, tourism oriented. That again is no surprise since for many of these countries, tourism is their primary or secondary industry.

The pattern is quite different for the rest of Latin America. Care must be taken in interpreting these domains, particularly the educational domain. Note that no records are reported in that domain for Brazil, Chile, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. To conclude that there are no Web documents on academic servers in these countries would not only be misleading but completely wrong. Academic servers in these countries do not use second-level functional tags, they use acronyms for the individual university servers. A document on the Universidad Nacional Autonima de Mexico server would carry the second- and top-level domain name .unam.mx, for example and not .edu.mx. or .ac.mx. And, with the exception of the Dominican Republic, academic servers in these countries supply a large proportion of the Web documents for these top-level domains. Similarly there are a number of government source documents on non-government servers. For example, some Argentine government material can be found on the Universidad de Buenos Aires server, and some Peruvian government documents are on .net.pe.

The distribution of Web documents by second-level domain names follows a similar pattern in both the English, Portuguese, and Spanish speaking countries. Commercial documents are the most common, followed by academic documents (in those countries using the tags). The next most common are documents on the .net servers. There are relatively few .org and .gov documents and almost no .mil. There are proportionately more commercial documents in the Caribbean than in the larger countries. This may be a function of the very large differences in size and economic differentiation between the Anglophone Caribbean and the rest of Latin America.

The distribution of Brazilian and Spanish-American documents by second-level domain name and English publication is more interesting. Commercial documents are much more likely to be published in English than are any of the others. Next most common are academic, organization, and network documents, followed by government and military. There are very few Latin American military documents on the WWW. But what few exist are in the indigenous language of the publishing country. The reason for this, I speculate, is the target audience. The .mil documents are targeted to the military. There is no compelling need to publish the documents in anything but the indigenous language. Government documents may or may not have a uniquely domestic audience. Governments seeking to promote foreign investment will publish in English to facilitate reading by potential foreign investors. But they will also publish in the indigenous language to disseminate information to a domestic audience.

The target audience for commercial documents is often partially external. English is the common second language of most the world, and particularly so in Latin America. Therefore, to reach the rest of the world, those documents are published in English.

7. CONCLUSIONS

This paper addresses a broad range of related subjects: (1) domain names, (2) a taxonomy of Web documents, and (3) language and the Internet. It also offers a methodology for searching and counting Web documents by top-level and second-level domain names.

There are two approaches to top-level domain names: functional and geographic. Both are legitimate and useful. All Web documents carry one form or the other. The same is not true of second-level domain names. There is no inherent reason why Internet Web documents must carry a second-level name, except that its use greatly facilitates searching and finding relevant documents and improving the recall of those documents. For that reason alone, I suggest that hosts and server registrars consider adopting the second-level naming practices.

Second, we as librarians and information specialists understand that the form of a document affects the way it is used, stored, referenced, and retrieved. Serials are treated differently from monographs, microfiche from print, and WWW from listservs. Various groups, including OCLC and the US Library of Congress, are developing means to effectively catalog these new electronic media. To be more effective, we need to differentiate among the types. This differentiation includes not only Internet groups: WWW, listservs. ft, newsgroups, and so on. We must also differentiate among the type of documents found on the WWW. I have suggested three: gateways, jumps, and content pages.

Third, it is probably wrong to argue that English

is the language of the Internet. Clearly most WWW documents are written

in English, but this is in large part because most WWW documents emanate

from English speaking places. If location is controlled for, English is

much less important as a publication language. The evidence suggests that

the rate of increase of new English language documents is slowing, while

the number of non-English documents is increasing. This trend will likely

hold as non-English speaking areas develop and implement their Internet

infrastructure and capabilities. To put this tritely, almost every college

sophomore in the United States has access to the Internet and a great many

of them have mounted their own homepages. In the developing world, access

to the Internet is often limited to political, economic, and academic elites.

As more "college sophomores" gain access to the Internet in these developing

countries, and I am convinced they will, the volume of material will continue

to explode. Moreover, so will the amount of the trivial and the trash.

REFERENCES

Cabezas, A. (1995). Internet: Potential for services in Latin America. IFLA Journal, 21: 1.

Ciurlizza, A. (1996). The Network of networks project: Electronic communications and CD-ROM data storage: Some challenges for information delivery," New Library World, 97: 1126.

Dias, E. (1994). Relatorio-General de Biblios 2000, General report on books 2000. Revista da Escola de Biblioeconomia UFMG, 23: 1.

Hollis, D. (1994). Latin America and Africa: A status report on the Internet. FID News Bulletin, 44, 11.

Mansilla, E. (1995). The Internet in Latin America: The benefits of the personal touch. Information World Review, p. 107.

Resnick, R. (1995). Ole. Latin America's net presence is growing. Internet World, 6: 4.