Robert S. Runyon

Libraries

University of Nebraska at Omaha

Omaha, NE 68182-0237, USA

E-mail: runyon@unomaha.edu

http://revelation.unomaha.edu/library_home.html

1.1. Functional Illiteracy

It is ironic that in the U.S., an advanced country and world leader in the development and applications of science and technology, there is a large and growing population of low-literate or functionally illiterate citizens. It is estimated that:

According to some estimates, the number of functionally illiterate individuals in the United States grows by more than two million persons each year. As these people move out of formal school systems into adult responsibilities, their major recourse for acquiring basic literacy skills is a loosely organized infrastructure of poorly trained volunteers that reaches less than 5% of those in need of instruction.

1.2. Non-literacy

"A person may be classified as non-literate who cannot read a text with understanding and write a short text in a significant national language, cannot recognize words on signs and documents in everyday contexts, and cannot perform such specific tasks as signing his or her name or recognizing the meaning of public signs" (Wagner, 1993). The dividing line between low- and non-literate populations is not precise. Only rough estimates are available for the size of each group by country. Generally, the negative impact of non-literacy is especially great in developing or third-world countries, where whole segments of society have been denied access to the means of education. In all countries, illiteracy deepens the large and growing division between rich and poor, and contributes to a profligate waste of human talents needed for productivity and development. The impact of illiteracy in the third world, especially in parts of Asia and Africa, generally weighs much more heavily upon women than upon men.

2. Learning to read

2.1. Pathways to Literacy

The home and school are the traditional centers for basic reading instruction. Parental guidance, encouragement and modeling are essential to all directed learning. Learning to read is an early childhood experience in which parents exercise a significant lifelong impact for good or ill. It has been reported that regular, daily reading by parents to their children is one of the strongest influences upon the children later becoming active and proficient readers. Thus children with non-reading, low-literate or illiterate parents start out with a significant deficit in the learning assets column of early childhood.

Many factors contribute to the alarming growth in the rate of illiteracy in the U.S. Within disadvantaged neighborhoods of most inner cities, there is a scarcity environment in which adequate schooling, high quality reading materials, and personal success models are unavailable. Family disintegration, joblessness and violence have a negative, synergistic impact.

Diagnosis and treatment of learning disabilities have made some strides in special education programs in better financed school systems. Even where special education programs are available, however, they are usually restricted to expensive private school settings. It is likely that learning disability problems are seldom adequately diagnosed or treated for vast numbers of children, especially those from underprivileged families.

There is speculation that a majority or as much as 75% of functionally illiterate adults who are received in literacy tutorial programs are subject to learning disabilities. At the same time, assessment procedures in these programs are not sufficient to identify such disabilities. Likewise the curriculum materials and teaching strategies of volunteer-based tutorial programs are not geared to dealing effectively with complex learning disability problems.

3. The Literacy Support Infrastructure

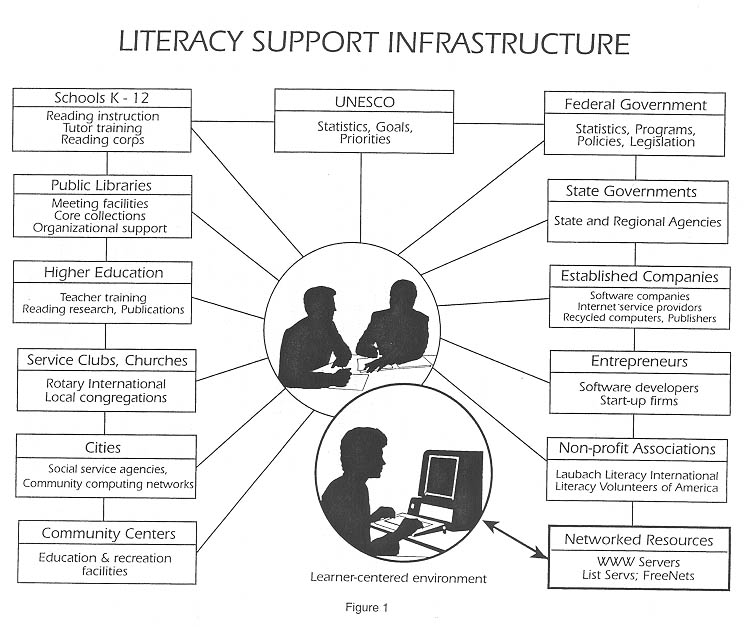

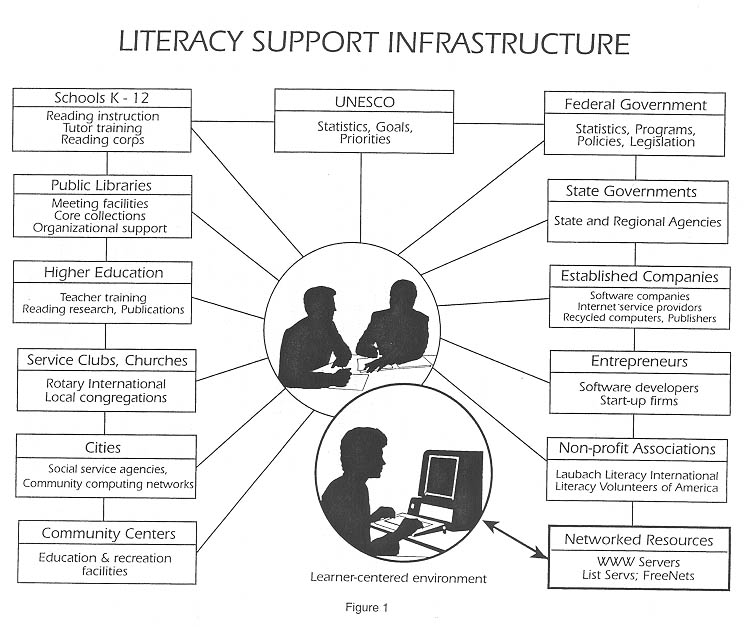

Figure 1 portrays organizational components of the evolving U.S. literacy support infrastructure. Many of these functional components are now in place. Others are part of an

emerging vision of what seems possible through literacy-based applications of new information technologies. While the components are many and diverse, they are also parts of

a very loosely coupled and sometimes overlapping system. "..The infrastructure system for adult literacy education is at best rudimentary. Development has been constrained by insufficient funds, the prevalence of part-time programming, service fragmentation, and structural marginality." (Beder, 1996)

3.1. Traditional Institutions and Programs

The first institutional providers of reading instruction in the life of the child are the Schools K-12. Teachers, textbooks and classes are introduced in this setting to move students through a graded series of formal learning experiences. Libraries within the schools offer resource materials and guidance considered essential for early childhood reading experience and instruction.

In parallel with the schools are Public Libraries that may offer extensive hours of availability, coupled with professional assistance for new readers, opening up unexpected vistas of reading opportunity.

Within the framework of Higher Education, school teachers are offered formal training in reading instruction. Universities are primary organizations for conducting research and publication on the pedagogy and development of reading skills.

Government and public service groups are also heavily involved in the literacy support infrastructure insofar as they provide program enabling legislation, policies, data, funding and products related to reading instruction. A network of government entities indicated on the chart are UNESCO, Federal Government, State Governments, Cities, Community Centers.

3.2. Learner-centered Programs

As a student becomes an adult, moving out of the tightly structured, public school instructional framework described above, there are other informal or back-up sources for acquiring missing or underdeveloped reading skills. These are often, but not exclusively, tutorial or learner-centered modalities.

Likewise Service Clubs, Rotary International for instance, have organized their members to offer programmatic support for local literacy organizations. Some Churches have also organized membership committees to provide literacy tutorial programs.

Within the last five years, Cities, universities and media broadcasters have established community computing networks. Sometimes called Free-Nets, Civic Networks, or Community Wide Education and Information Services, these systems have diverse names, and encompass a broad range of local and regional models affiliated with the National Public Telecomputing Network. They provide computing, communication and information services to citizens, organizations, businesses, government agencies, schools, libraries, and the established media. Free-Nets don't typically offer literacy support instruction, but in the future they could become major network sources for such instruction. (Meenan-Kunz, 1995)

New Distance Education delivery systems are also rapidly springing up in universities, junior colleges, and even in high schools. An innovative scheme announced in June 1996, is the Western Governors University (WGU). Established by the Western Governors Association in June 1996, this multi-state, non-profit consortium will market educational services and accredited degree programs across state boundaries in the western U.S.. Its goal is "To remove the obstacles of both time and place to post secondary education opportunities for individuals and corporate citizens of the West by developing and demonstrating innovative, cost-effective approaches to delivering education through the use of rapidly evolving advanced technology" (See WGU WWW server).

Other new technology partners and providers are rapidly emerging. These include Entrepreneurs and Networked Resources.

4. Strategies

4.1. Time on Task

For adult learners served by the agencies described above, a central problem is early attrition of students and tutors. Non-readers find it extremely difficult to acquire the skills base and study discipline that eluded them during frustrated earlier attempts in the formal schooling process. Good intentions are often not enough and students drop out of the learning process due to a myriad of factors including the pressure of other life problems and responsibilities. Tutors too have a high rate of attrition as they find the task more intractable and the results more elusive than they expected.

Even brief experience as a literacy tutor reveals that it is difficult to elicit sufficient student "time on task" to achieve progressive reading results. Typically the adult student has neglected reading for so long that it requires a strong commitment to a life-style change in order to succeed at such a demanding task. Thus a primary need for the literacy tutor is to instill the motivation and persistence necessary to keep a student working on his or her own long enough to develop tediously acquired incremental skills.

One reading researcher and literacy tutor put it this way. "Think of all the words you've ever read as so many pennies deposited in a bank. As a literate adult, the pennies you have accumulated over the years would fill a large vault. Your adult literacy student with only a third grade reading level (and apparent dyslexia) has accumulated only enough pennies to fill a small box. Therefore get him to read as much as you can. You need to encourage him to build up his deposits of pennies in the word bank."

For every literacy tutor, a key practical question is how to provide materials and structure for the student to learn independently through the completion of regular homework assignments. Each tutor must find effective ways to increase his student's "time on task" This should also be time when reading and writing are fun and not just mechanical exercises.

4.2. Technology

New approaches, and possible answers to this dilemma, are suggested by rapidly developing computer and telecommunications technologies. What might be accomplished if literacy students had access to computers on which to practice and work on appropriately structured materials? There is very little evidence to answer this question today. There are strong indications, however, that when computers are situated in public library settings, they become incentives for independent study and enjoyment.

At the Brooklyn Public Library, which houses one of the largest literacy programs of any library in the U.S., it was reported that "Computer-assisted learning proved to be an incentive; the machines are in almost constant use." (Malus, 1987, p. 39)

The power, speed and memory capacity of the latest model microcomputers are doubling about every eighteen months to two years. Although computer unit cost in relation to performance is dropping precipitously, the rapid rate of new market displacement for older hardware models and software releases is a source of serious concern, especially for educational institutions. The expenses necessary to acquire and maintain up-to-date computer equipment in schools and learning centers are staggering. Given the mounting costs, it is extremely difficult for publicly funded agencies to maintain systems currency. This situation is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

The Computers for Schools Program of the Detwiler Foundation is one example of an organization with a strong acquisition and distribution network for recycled computers. The foundation's program vision and purpose is summarized in the statements below:

AT STAKE: The future of California's students.

THE GOAL: One million donated computers.

NEEDED: Participation by every individual and company

that shares in California's future.

An executive of a large telephone company reported, "It is very difficult to give something away. We struggled with how to send our surplus computers to the schools and the Detwiler Foundation provided the means for us to do that....Getting others to have this vision is not hard, but to put together the process to make it happen without extra expense to the business is very difficult." Extensive WWW pages in the following section provide guidelines for donating computers as well as documentation and testimonials for developing awareness and program participation.

"Others in the field of adult literacy express a need for information about free and inexpensive software as well as the establishment of a mechanism for recycling computers. Public domain software that can be copied freely is recommended for tutors and learners in volunteer programs beginning at the lowest levels. Concern for empowerment of learners drives both the desire for free software and the use of real world applications; the belief is that those in need of literacy services are the last to receive technology and to have access to information." (Turner, p. 21)A different approach to computer recycling by a U.S. corporation was announced in an electronic newsletter addressed to Union Pacific Railroad employees. "Under the partnership agreement, Union Pacific will release excess or retired IBM-compatible computers to the Nebraska Lions Foundation. In turn, the Lions will inspect the equipment, perform any necessary maintenance and donate it to appropriate individuals and nonprofit organizations throughout Union Pacific's 23-state operating area." (Union Pacific, 1996).

In other instances, local clubs of Rotary International have begun to organize computer solicitation programs from their members and local businesses on behalf of municipal literacy councils. One club plans to offer its recycled computers to literacy students on a six month loan after which they will be reclaimed and offered to others in need.

An Omaha hospital recently donated 30 IBM PS/2-286 model computers to the Omaha Literacy Council for use in student homes. Volunteers are currently searching for literacy tutorial software to use on these machines. The hospital's alternative was sending the machines to a landfill or a rare metals recycler.

One negative aspect of starting with free hardware and then looking for compatible software, is the reversal of the recommended approach to system components selection. Typically, a system administrator should begin by defining educational goals and intended learner outcomes, next identify effective and compatible software, and later the hardware that will fulfill those functions.

It can be argued, however, that providing adult literacy students with personal computers, however old and poorly equipped, is a big step in the right direction. Various reading, typing, word processing, communications and games software can support student motivation for independent study and continuing literacy program participation.

• Learning networks

"The Web has grown very fast. In fact, the Web has

grown substantially faster than the Internet at large, as measured by number

of hosts. The rate of the Web's growth has been and continues to be exponential,

but is slowing in it's rate of growth. For the second half of 1993, the

Web had a doubling period of under 3 months, and even today the doubling

period is still under 6 months" ("Internet Statistics, Growth and Usage

of the Web and the Internet" <http://www.mit.edu:8001/people/mkgray/net/>).

6/93 130

12/93 623

6/94 2,738

12/94 10,022

6/95 23,500

1/96 100,000

6/96 (est) 230,000

Increasing amounts of highly useful information regarding literacy are appearing on the Internet, especially on World Wide Web home pages. The completion of this paper was delayed by the late but fortuitous discovery of vast unknown materials through the Web. A sampling of key sites and URL's follows:

Philadelphia, PA 19104-3111 Phone: 215-898-2100

E-mail: ncal@literacy.upenn.edu

<http://litserver.literacy.upenn.edu/Default.html>

The NCAL at the University of Pennsylvania is an incredibly rich and comprehensive source for the latest research, practice and policy documents in the field of adult literacy. NCAL has operated since 1990 under major grants from the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Departments of Labor and Health and Human Services. It was established to provide national leadership for research and development in adult literacy.

Along with its extensive World Wide Web server pages indicated above, NCAL recently published the Adult Literacy Explorer, An Interactive Information Software Program for Adult Literacy, Version 2.0, 1996. This CD-ROM, available in both Macintosh and Windows formats, provides a multimedia exploration of adult literacy in the U.S. It is unquestionably the best documentary source available anywhere for adult literacy information.

Major sections are: national literacy policy and organizations, state literacy profiles, adult literacy reports, and technology use in adult literacy. The technology area is further subdivided into: technology planning, hardware and software evaluation, networks, adult literacy software (includes a database and demonstration versions of many of the software packages), technology fundraising, and technical terms glossary.

The CD-ROM contains an NCAL Publications Archive with electronic copies of all NCAL publications completed through March 1995. A bibliography indicates that 51 major NCAL reports were completed by the above date. That number rose to 69 by May 1996. The archive can be used either in browse or search mode.

The combination of text, pictures and narration on this CD-ROM allow it to be used effectively with a projection device for presentations to groups. The extensive database search and browse features permit it to be used as a researcher's library for consultation of the latest information and data in the field. The CD-ROM, sells for $35.00.

Institute for the Study of Adult Literacy, Pennsylvania State University <http://www.psu.edu/institutes/isal/>

National Institute for Literacy

<http://novel.nifl.gov/HomePage.html>

Online Adult Literacy Sources

<http://www.mlin.lib.ma.us/literacy.htm>

Nebraska Institute for the Study of Adult Literacy

<http://www.unl.edu/dvae/otherprograms.html#AL>

-Computer Technology Survey <http://archon.educ.kent.edu/~nebraska/survey.html>

Internet Directory of Literacy & Adult Education Resources

<http://literacy.nifl.gov/litdir/elandh/hsubjndx.htm>

Literacy Volunteers of America (LVA)

<http://archon.educ.kent.edu/LVA/>

National Adult Literacy and Learning Diabilities Center, University of Kansas <http://novel.nifl.gov/nalldtop.htm>

The Detweiler Foundation. Computers for Schools Program

<http://199.2.50.5:80/detwiler/>

Davis Dyslexia Association International

Dyslexia - The Gift <http://www.dyslexia.com/>

George's Dyslexia Resource Links

<http://www.iscm.ulst.ac.uk/~george/subjects/dyslexia.html>

Dyslexia: The Gift. Information for Parents and their Children

<http://www.iscm.ulst.ac.uk/~george/subjects/dyslexia.html>

Orton Dyslexia Society

<http://ods.pie.org/T3639>

Dyslexia - My Life

<http://www.qni.com/~girards/>

Poor Richard's Publishing - Resources for the learning disabilities community

<http://www.tiac.net/users/poorrich/index.html>

Don Johnson Products for learning disabilities

<http://www.donjohnston.com/>

Official Rotary International Homepage

<http://www.rotary.org/index2.html> <http://www.tecc.co.uk/public/PaulHarris/enh.index.html>

- An Unofficial Guide to Rotary <http://www.tecc.co.uk/public/PaulHarris/enh.index.html>

Sister Cities International

<http://www.sister-cities.org/index.html>

Western Governors University

<http://www.westgov.org/smart/vu/vu.html>

National Public Telecomputing Network

<http://www.nptn.org>

"It seems clear that a library, properly managed, and made available for the practical and scientific purposes of a community, should tend to increase the ability and resourcefulness of that community, especially if it is so managed as to meet the constantly changing demands of the day as science grows." (Carnegie, 1948)Carnegie's vision of the role of the library helped to define the public library movement in the U.S. He also foresaw that libraries would adapt to the "demands of the day." And indeed they are moving rapidly into the digital age, supplementing traditional print collections with electronic databases and network access workstations for public usage.

"Libraries provide unique opportunities in literacy instruction with their long hours and community orientation. Furniture is designed for adults and the buildings are not schools. Technology works well in such an environment where librarians, long accustomed to the use of computers for cataloguing and communicating, have an easier time understanding its potential than do many teachers and tutors.Several books outline strategies, plans, and specific programs for implementing literacy support programs in libraries (Salter & Salter, 1991; Weibel, 1992; Rosow, 1995; Weingand, 1986; Lyman, 1977).Perhaps the most significant contribution of the library to the literacy field is a new way of thinking about literacy. As librarians have rethought their role in the information age, they have broadened the thinking of literacy professionals as well. Access to information through a wide range of modalities, one of which is the book, is a major library theme. Literacy professionals, bound by the constraints of print literacy, are beginning to envision a world in which the teaching of literacy skills encompasses all the senses." (Turner, 1993)

4.4. Welfare Structures for Assisted Self-development

Recent changes in U.S. federal welfare laws may help to highlight the needs for expanded literacy instruction. New federal legislation opens up heretofore untried mechanisms for states to contract out welfare services to private companies. "Before the new welfare law, moving people from welfare to work was the domain of nonprofit organizations and three relatively small businesses. Now, some large companies see a potentially multibillion-dollar industry that could run entire welfare programs for states and counties" (Bernstein, 1996). In a The New York Times article, it is indicated that large information systems vendors are now bidding on state contracts for welfare services. Some of these such as, Lockheed Information Services and Electronic Data Systems, already have multi-million dollar contracts for provision of administrative systems support to state welfare agencies.

Under the new law, fixed price, performance-based contracts may be written with guarantees to move specified numbers of welfare recipients into paying jobs within two years. With this degree of accountability for results, one may expect increased attention directed to the role of low-literacy in unemployment. A higher priority may be given to literacy instruction as a way to move welfare recipients into productive employment. If this is the case, a vast new market will be created for technological "solutions" to the growing problems of illiteracy. "Interactive computerized instruction programs have been little used in welfare-to-work programs. However, they appear to have considerable promise in overcoming the barriers of motivation and shame associated with standard one-on-one tutoring or small group classroom instruction." (Cohen, 1994)

Two approaches suggested here are literacy tutorial software and network-based servers and resources for distance education. When lucrative contract offerings are coupled with big corporation information systems expertise, a much higher priority is possible for literacy software development and training facilities. "The consumer market appears to have great potential for the development of adult literacy software. There are approximately 50 million potential adult literacy students, and many of these could be reached in their homes." (Harvey-Morgan, 1996)

4.5. International Collaboration

Certain non-governmental organizations have been instrumental in furthering collaborative international programs for addressing illiteracy and non-literacy.

Rotary International has identified literacy as one of its primary themes in World and Community Service. The Rotary Foundation provides grants that support literacy projects on a multinational basis. In South Africa, where black children who speak the vernacular need to learn standard English, the Rotary Club of Sandton donated tape recorders, typewriters and personal computers to the South African "Write to Read" literacy program.

Sister Cities International is involved in building community partnerships worldwide. "The Sister Cities program is an important resource to the negotiations of governments in letting the people themselves give expression of their common desire for friendship, goodwill and cooperation for a better world for all." (Dwight D. Eisenhower)

References

Beder, Hal. (1996, January). The Infrastructure of Adult Literacy Education: Implications for Polity. Washington, DC: US National Center for Adult Literacy. NCAL Technical Report TR96-01. p. 9.

Bernstein, Nina. (1996, September 15). Giant companies entering race to run state welfare programs. New York Times, CXLV (50): 551. p. 1.

Bowen, Betsy A. (1994). Telecommunications networks: Expanding the contexts for literacy. N: Selfe, Cynthia L. and Susan Hilligoss. ed. Literacy and Computers: The Complications of Teaching and Learning with Technology. New York: The Modern Language Association of America.

Clark, Diana Brewster and Joanna Kellogg Uhry. (1995). Dyslexia: Theory & Practice of Remedial Instruction. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: York Press.

Carnegie, Andrew. (1915). A Carnegie Anthology. Arranged by Margaret B. Wilson. New York: Privately Printed.

Carnegie, Andrew. (c1948). Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 272.

Cohen, Elena, et. al. (1994). Literacy and Welfare Reform: Are We Making the Connection? NCAL Technical Report TR94-16. Washington, DC: US National Center for Adult Literacy. p. 2.

Duin, Ann Hill and Craig Hansen. (1994). Reading and writing on computer networks as social construction and social interaction. In Selfe, Cynthia L. and Susan Hilligoss, ed. Literacy and Computers: The Complications of Teaching and Learning with Technology. New York: The Modern Language Association of America.

Fordham, Paul, Deryn Holland, and Juliet Millican. (1995). Adult Literacy: A Handbook for Development Workers. Oxford: Osfam -Voluntary Services Overseas.

Fukuyama, Francis. (1995). Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Harvey-Morgan, Joyce. (1996, May). Moving Forward the Software Development Agenda in Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: US National Center for Adult Literacy. Practice Report PR96-02. p.2.

Lyman, Helen Huguenor. (1977). Literacy and the Nation's Libraries. Chicago: American Library Association.

Main, Linda and Char Whitaker. (1991). Automating Literacy: A Challenge for Libraries. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Malus, Susan. (1987, July). The logical place to attain literacy, Library Journal. pp. 38-40.

Meenan-Kunz, Avis. (1995, October). Community computing. Mosaic: Research Notes on Literacy (Institute for the Study of Adult Literacy). 5 (1): 5.

Nelson, Theodor H. (1992). Opening hypertext: A memoir. In Tuman, Myron C. ed., Literacy Online: The Promise (and Peril) of Reading and Writing with Computers. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Rosow, La Vergne. (1995). In Forsaken Hands: How Theory Empowers Literacy Learners. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Salter, Jeffrey L. and Charles A. Salter. (1991). Literacy and the Library. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Turner, Terilyn C. (1993, April). Literacy and Machines: An Overview of the Use of Technology in Adult Literacy Programs. Washington, DC: US National Center for Adult Literacy. Technical Report TR93-3. p. 37.

Union Pacific Railroad. (1996, September 5). Online, No. 187.

Wagner, Daniel A. (1993, June). Literacy and Development: Rationales, Assessment, and Innovation. Washington, DC: US National Center for Adult Literacy. LRC/NCAL International Paper IP93-1.

Wagner, Daniel A. and Richard L. Venezky. (1995, May). Adult Literacy: The Next Generation. An NCAL White Paper, NCAL Technical Report TR95-01.

Weingand, Darlene E. ed. (1986, Fall). Adult education, literacy, and libraries. Library Trends, 35 (2).

Weibel, Marguerite Crowley. (1992). The Library as Literacy Classroom: A Program for Teaching. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Wilson, William Julius. (1996). When Work Disappears:

the World of the New Urban Poor. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.