CRITICAL DECISIONS FOR DEVELOPING THE ELECTRONIC LIBRARY

Diane Tebbetts

University Libraries

University of New Hampshire

Durham, NH 03824-3592, USA

E-mail: diane.tebbetts@unh.edu

The development of the electronic library is an exciting step into the world of computers, networks, and cyberspace. In this world, time and physical distance become meaning-less. One can surf the network from New York, to London, to Hanoi in a matter of seconds. Brian Hayes writes: "One answer to the question 'Where is cyberspace?' is that it has its own geography. The Internet is said to span national boundaries and make neighbors of people who might otherwise be isolated. Thus it is a kind of parallel universe, where distances are measured with a different metric" (Hayes, 1997, p.214). Resources that used to take weeks and months to receive by ship or days by airplane can now be displayed in seconds on a computer screen. In the excitement of this vast computer network it is easy to forget that cyberspace is dependent on the very real physical world of wires, cables, and machines. Before one can venture into this vast invisible world it is necessary to wire buildings, lay cables, make telecommunications connections, and acquire hardware.

There are many options in this electronic world. Beginning the development of the electronic library at this time has many advantages. It is possible to bypass early stages of development, to learn from the mistakes of others, and to avoid costly diversions. At the same time, the array of options is extensive. Picking and choosing the appropriate applications can be difficult. This paper will consider some of the basic components and the options available. The best choices for a specific library will vary depending on the available local resources, the goals and objectives of the library, and the personnel trained to implement the selections.

2. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Before looking at specific options for developing the electronic library, it is important to consider some general guidelines. It is essential to have a clear vision of the general direction in which to proceed. Without this basis it is easy to become intrigued by a specific application which may or may not be of long-term value to the library. As with so much in library service, it is vital to begin with a plan.

2.1. INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY PLAN

As with any planning effort, the Information Technology Plan begins with a survey of the environment. It is essential to understand the local situation. Critical to the successful implementation of information technology is the infrastructure necessary to set up the hardware, wire the buildings, and make the connections to external resources. While it is likely that elements of the infrastructure will have to be developed, it is important to understand the current situation and to assess the needs. The Information Technology Plan will provide a framework for estimating the available resources and implementing systems on that basis. The Information Technology Plan is not a static document. It will evolve as the situation changes, but the general goals will remain constant. In this quickly changing environment it is important to keep in mind the overriding goals of the institution. As David Barber writes: "Much of the art of digital library building is careful strategy. System developers need to make the best bets they can on present and future technologies in order to avoid limiting future flexibility and most of all to avoid large investment in ephemeral technologies... The focus on strategy is important because it directs attention from specific technologies that are here today and gone tomorrow to the broader issues that need to be addressed" (Barber, 1996, pp. 578-579).

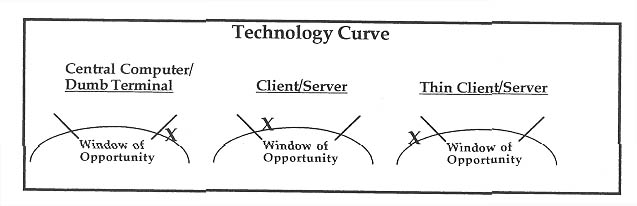

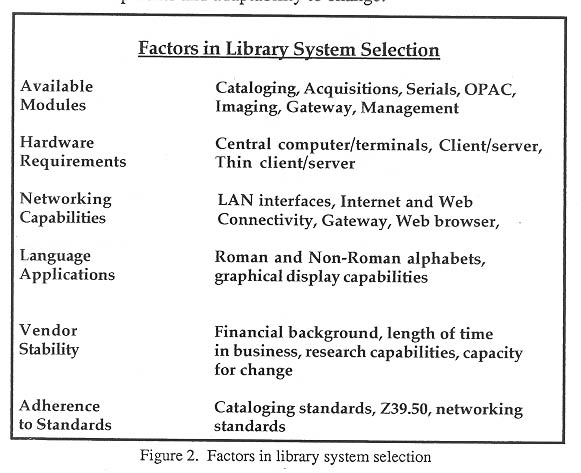

2.2. TECHNOLOGY CURVE

Deciding when to invest in a new technology or adopt a particular application is extremely difficult. Much depends on the local situation, but the maturity of a particular technology is also relevant. David Barber presents this evolutionary development as an S-curve with time on one axis and acceptance on the other. The technology starts slowly, gains momentum when many people adopt it and then tapers off and is overtaken by other developments (Barber, 1996, p.588). It can also be described as a window. There is a "window of opportunity" when it is best to implement a particular technology. Viewed on a continuum, early adoption of a technology is risky because it is not fully developed. The technology may not develop as promised, it may go through several stages before it becomes fully workable, or it may get overtaken by other products. On the other hand, late adoption of a technology may put it at the end of its life span. Other products may make it obsolete before the library has been able to use it to any extent. This is always demoralizing for staff and may be viewed as a waste of money.

Clearly, determining the best time to implement a technology is a matter of judgment that has to be based on an assessment of the technology itself and the local situation. Barber asserts: "...there are risks both to being early and late adopters of technology. There is no perfect place to be on the evolutionary curve. The right place is determined by the character and resources of the organization involved. For most organizations, late adoption of technology is a more comfortable strategy" (Barber, 1996, p. 592). Trying to find that midpoint, the "window of opportunity" would seem to be the best approach. Keeping up on technological developments, assessing the relative merits of varying approaches, being wary of very new products, and not being tempted by "test" projects unless aware of the possible consequences are some approaches in helping to determine the best time to implement a new technology. Again, as Barber writes: "When building a digital library, it is important to look at the evolutionary curves for the main technological ingredients of the services that are being built. Consider the path of change in computer power, Internet software, and related technologies. The position of the technologies in their evolutionary history must be weighed with the level of risk with which a library is comfortable" (Barber, 1996, p. 593).

2.3. PLANNING FOR CHANGE

In the fast-paced world of information technology it is essential to understand that change is the one constant. Planning must take this into consideration. Barber declares: "...there is no end point to this technological change. One has to be prepared to reevaluate what one has done. A sense of permanence is elusive in this environment. Plans for one-time skill changes and one-time investments are erroneous ideas in a world of continual change" (Barber, 1996, p. 593). Decision-making in this environment has to focus on flexibility and adaptability. The ability to interface systems, to migrate from one system to another, and to connect to outside resources is essential. Proprietary systems that demand specific hardware, or local implementations that are designed for an individual institution and cannot interface with other systems should be avoided. Although it may be tempting to develop a local system with unique programs, this approach will most likely limit flexibility and connectivity. More widely used hardware and software will most likely provide less risk and the ability to change and adapt to new developments.

2.4. ADHERING TO STANDARDS

To maintain maximum flexibility and connectivity, it is vital to adhere to standards as much as possible. From MARC to Z39.50, standards play a role in almost every aspect of the online library system. The records in the database must follow standards so external records can be added to the system. In acquisitions, adherence to the EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) standard permits the exchange of data between the library and vendors including invoicing information. In the OPAC (Online Public Access Catalog), the implementation of the Z39.50 protocol allows the user to search multiple databases using the same search strategy employed by the library's local system.

The use of standard protocols allows the local system to interact with external computers for a variety of reasons. When purchasing a new system or developing enhancements to the current system, it is important to consider these factors. As standards become more accepted by the library community, they become regular features on vendors' offerings. However, it is always wise to review the use of standard protocols.

3. THE BASICS: OPTIONS AND DECISIONS

The basic elements of the electronic library are hardware, software, and networking. In discussing the options it is essential to remember that these three components interact with each other in a complex mix. If one decides on a particular type of hardware it will determine the software alternatives and the networking requirements. On the other hand, if a particular library system is chosen, then that will determine the hardware choices and the networking capabilities. For the purposes of discussion we will examine the hardware, software, and networking options separately keeping in mind the interaction among them.

3.1. CENTRAL COMPUTER/DUMB TERMINALS

The configuration of hardware that has supported library systems from the earliest developments has included a large central computer running the software application and "dumb terminals" serving as the output devices. In this scenario, all the operations are performed on the large central computers (mainframes or minicomputers) and the terminals are limited to querying functions and displaying results. Over the years, this arrangement has served libraries well. The major cost is the central computer, while the terminals are fairly inexpensive. The terminals are easy to operate since the functions that can be performed on them are limited. They are connected to the central computer and restricted to the operations the library determines. The OPAC terminals can be programmed to perform only that function. The library does not have to be concerned that the terminals are being used for other purposes because they do not have that capability. However, terminals cannot perform complex tasks or display graphics so they can only display text. This limits severely their usefulness in accessing the Web.

Older library system installations usually have this configuration. In moving in the direction of the electronic library, it becomes increasingly important to provide more powerful workstations that can perform a variety of functions, display graphics, manipulate data, and connect to external resources. Terminals do not have these capabilities, and it becomes necessary to migrate to systems and hardware that can support more complex functions.

In setting up a new installation, it is important to consider the alternatives and weigh the pros and cons. The pros and cons for this type of installation are:

Pros:

• All the applications run on the central computer. It can be located in a central site and maintained by experienced personnel. The central computer can be located in the library since there are no longer complex site requirements, but it is important to maintain a fairly constant temperature so some air conditioning might be required, especially in a tropical environment.

• The terminals are easy to maintain because they do not contain complex components. Users cannot manipulate them or perform functions other than those determined by the library.

• Terminals are not expensive. Three or four can be purchased for the cost of one PC. This provides more access points for users.

• It is not a new technology. Most library systems began with this hardware configuration and many still use this technology so the requirements and techniques for managing the system are well-known.

• Internet access is possible from terminals connected to central computers but the information that can be displayed on terminals is limited to textual.

• In developing countries, this may be the system that telecommunications and wiring capabilities can support and from a practical perspective may be the best approach.

Cons:

• This is an older technology. On the "technology curve" this type of installation has passed its peak or optimum period of implementation.

• Full use of the Internet and the Web is not possible on terminals. It is necessary to have PCs to present graphics, manipulate data or save results on the workstation.

• Integrating internal and external resources is much more limited with terminals to access the database.

• Additional functions or library operations cannot be interfaced as easily on this type of system. For instance, a program to manipulate statistics cannot be run on the workstation if it is a terminal. The central computer would have to run the statistics and display. Therefore, it is more difficult to interface an independent statistical package on this type of system.

• The wiring for this system is different from that necessary for the client/server installation. If you switch to the client/server approach later, it will require rewiring.

3.2. CLIENT/SERVER

In the development of library systems the trend is clearly in the direction of the client/server configuration in which computing operations are shared. William Saffady writes: "For their newest integrated systems, vendors are increasingly emphasizing client/server implementations in which computing tasks are distributed among a shared computer (the server) and microcomputer-based workstations (the clients). The servers in such configurations are typically Unix-based computers. Several vendors offer Windows NT servers, and more are likely to do so. Client workstations are typically Windows-based microcomputers. A few vendors also support Macintosh or Unix-based clients" (Saffady, 1997, p. 133).

Another writer provides the following definition of the client/server infrastructure:

In considering this type of installation, the advantages and disadvantages of client/server are summarized as:

Pros:

• This is the type of installation with the most promise for future development. On the "technology curve" it is entering the optimum time for implementation. It is not so new that it is risky, and it is becoming widely available. Many library vendors are offering this configuration or moving older systems in this direction.

• It is the technology necessary for providing a Web-based OPAC on which local and external resources are both made available.

• High-powered PCs as workstations provide the capabilities for displaying graphics, downloading documents to disk, manipulating data, and accessing full-text databases.

• A client/server approach accommodates remote access to the library's integrated system from PCs located outside the library. In a fully networked environment this allows users to search the library and its resources from home, office, or other campus buildings.

Cons:

• There are costs associated with this approach. While the server (central computer) tends to be less expensive than the mainframes or minicomputers, the clients (microcomputers) are more expensive than "dumb" terminals. Since several clients are required for public and staff workstations, this can be an important factor.

• Whereas "dumb" terminals require no application software, client PCs require desktop software to enable them to perform the functions required. This means that system personnel will have to set up and maintain the PCs.

• "Dumb" terminals are extremely easy to operate. Usually they are menu driven and require simple keystrokes to operate. PCs on the other hand, have more capabilities and require more instruction in their use. If a graphical user interface is employed, users will have to learn to operate the "mouse." This also will probably require more instruction.

• With word-processing software and networking capabilities available on the public workstation, it may be tempting for users to perform functions other than library operations thereby monopolizing the equipment.

3.3. THIN CLIENT/SERVER

The latest developments in this area involve the client part of the system. As we noted above, PCs operating as clients have cost implications as well as operational considerations revolving around staff time for maintenance and upkeep of the microcomputers. To offset these drawbacks, companies are developing "thin" or "lean" clients which are also known as "network" PCs or "NetPCs." Network computers do not have hard drives or other storage devices and they do not have software applications residing on them. However, they do have networking capabilities and the ability to interact with other computers on the network and utilize software applications such as Java. Several manufacturers are in the process of introducing NetPCs. Compaq has brought out the Deskpro 4000N and NEC has the NEC PowerMate Enterprise NetPC. Both of these are powerful PCs without storage devices and the prices range between $1200-$1400 which is close to an inexpensive microcomputer (Gerding, 1998, p. 1). Intel has announced a simpler version of the NetPC which "could be priced as low as $500. and would be able to run under a range of operating environments, including Microsoft Corp.'s multiuser version of Windows NT--code-named Hydra--as well as Java" (DiCarlo, 1997, p. 1).

Clearly, these NetPCs are an exciting alternative that would provide many of the capabilities of microcomputers without the costs but there are advantages and disadvantages to their implementation at this time.

Pros:

• Cost is a major factor. The NetPC is lower cost than a microcomputer. As discussed previously, the costs range from an anticipated $500 to $1400. It is likely that the NetPC would be a replacement for the "dumb" terminal. This would provide Web access and capabilities at a reasonable cost.

• The NetPCs could be managed remotely from the server thus centralizing the maintenance. David Gerding explains: "The main cost of ownership often comes from servicing and upgrading all the PCs on a network by hand. So what if your overworked IS staff could maintain your whole network of PCs remotely, essentially automating all that maintenance?" NetPCs offer that possibility.

• Software applications can be limited on the NetPC thereby eliminating many non-library uses, such as word processing.

Cons:

• This is a very new technology. Thin clients or NetPCs are just being introduced into the market. On the "technology curve" they are just at the beginning. At this time, it is not clear what will be the best product.

• While costs are lower than PCs, prices are still relatively high because the NetPCs are so new. It is likely that costs will come down as the product matures. This is evident by the announcement of the Intel NetPC under development.

• At this time, it is not clear how library system vendors will integrate this product with their systems.

• While the costs for the workstations are reduced, there are some costs that have to be switched to the server required to manage the NetPCs, so this must be considered in any cost analysis.

• It must be remembered that it is not possible to download to NetPCs because they do not have any storage devices so downloading must be transferred to a server or emailed to a user's file resident on another computer.

These are some of the hardware options for the electronic

library. Each option has advantages and disadvantages and choices depend

on the local situation, the library system, and the networking capabilities.

However, it is important to keep in mind the direction technology is taking,

where each option is on the "technology curve" and how easy it will be

to upgrade installations as future developments demand changes. However,

in general, Figure 1 shows the technology curve for each of the options,

with the left side of the curve signifies early adoption, the right side

of the curve late adoption, and the middle part of the curse the middle

range.

Figure 1. Technology curve for each of the option

4. LIBRARY SYSTEM - SOFTWARE

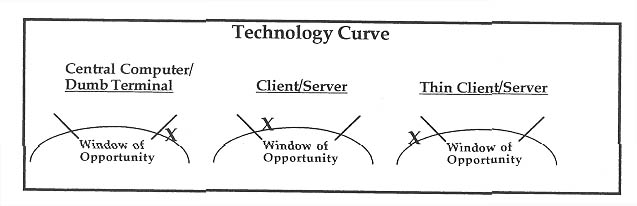

Which library system is chosen to automate the library is crucial to the capabilities of the library to change easily, to update functions, to implement Web-based features, to interface modules, and to accommodate remote users. It is evident from the preceding discussion that hardware requirements and software applications are interwoven. The decision to use a particular library system will have hardware implications and vice versa.

Of course, there are many reasons for choosing a particular library system. It is beyond the scope of this paper to go into this in detail. I have analyzed the factors at length in other papers. Figure 2 gives a listing of some of the factors that must be taken into consideration in the selection of a library system.

An analysis of system options based on these factors will help to determine which system is appropriate for a particular situation. The selection of a system is always dependent on the needs of the local library and the environmental conditions. Clearly, it is important to consider very carefully the hardware demands of any choices that are made. As we have seen, hardware requirements have associated costs, as well as implications for future developments and adaptability to change.

5. NETWORKING

Along with hardware and software, the third basic element in the development of the electronic library is networking. The availability of high-speed telecommunications is essential to the electronic library. These telecommunications networks can be local area networks (LANs) within libraries, wide area networks (WANs) connecting buildings on campuses, networks providing Internet access, and the Internet itself. As David Barber writes:

"Librarians do not need to be concerned about all of the minutiae of

network design, but they need to be aware of the fact that this design

provides them with a certain network capacity that can be used" (Barber,

1996, p..731).

There is now a network in Vietnam, Netnam, which provides access to the Internet. According to the Netnam webpage, it was established in Hanoi in December 1994 and expanded by adding a Southern server in February 1996. Netnam provides email, forums, databases, and Internet access. The webpage (Figure 3) indicates that there are 734 organizational subscribers to the network (Netnam webpage, 1998), and this number will certain grow fast.

As communications network is developing in Vietnam, libraries will be able to access these networks if they have the necessary equipment and connections in their local institutions.

Wiring within buildings is also of major concern. It is necessary to connect terminals to mainframes or minicomputers, or clients to servers. However, it is important to understand that each configuration requires different kinds of wires. "Old hard-wired serial connections used to connect dumb terminals to the host computer cannot be used to connect PCs to a Web server. Different cabling and networking architectures, such as 10Base-T,

will be needed to support Web-based computing. If that infrastructure does not exist, a major rewiring project must be designed and installed at considerable expense and aggravation" (Dennis, Carter, and Bordeianu, 1997, p. 161). If there has been no wiring in a building, it will be essential to begin that process, because internal wiring will be necessary for the development of the local system, the setup of LANs, or making the connections to the Internet.

There has been much speculation about the potential for wireless applications. Progress has been made in connecting to the Internet from cellular phones and cellular modems (Brodsky, 1995). However, the connections are slow and the quality of the transmission is variable making it difficult to transfer large files. Wireless LAN technology is also progressing making its use in local situations a possibility. However, it is most likely that these wireless LANs would have to interface with wired LANs. Recently, standards have been developed for interfacing wired and wireless LANs which is encouraging for the future progress of this technology. However, it is most likely that wireless technology will supplement wired rather than replace it (Blodgett, 1995). This technology is at the beginning of the "technology curve." It is important to watch it carefully to determine its viability and applicability to new installations. In the future, this may present a good alternative to extensive wiring, but it has not developed sufficiently at this time.

6. CONCLUSION

The implementation of the electronic library is dependent on a complex interaction of hardware, software, and networking capabilities. The library must have a plan for the electronic library based on the goals and objectives of the institution. With this overall vision guiding development, it becomes easier to decide on specific applications and approaches. The specific options and choices are dependent on the available resources and local capabilities. While it is essential to keep in mind the overall plan, it is also important to determine where a particular technology is in terms of the "technology curve." Implementing a technology when it is very new is risky and often costly. It may be too soon to know if a particular technology will become viable or whether it will be overtaken and replaced by more advanced products. It is also possible that it will never mature. On the other hand, choosing a technology at the end of its life may mean that its long-term application will be limited requiring the migration to newer products sooner than wished. This is often costly and demoralizing because it requires migrating systems, acquiring new products, and learning new skills.

Determining the right moment to acquire a technology

is an intelligent "guess" based on careful analysis of the current technology,

an awareness of the latest developments, and a thorough understanding of

the local situation and the available resources. David Barber writes: "While

individual technologies ... are based on science, their successful application

is an art form" (Barber, 1996, p. 578). Keeping in mind the need to plan

carefully, to study technological developments, to maintain flexibility

and to adhere to standards will help in choosing among the many options

available in developing the electronic library.

REFERENCES

Barber, David. (1996, September-October). "Building a digital library: Concepts and issues," Library Technology Reports, 32 (5): 573-736.

Blodgett, Mindy. (1995, June 12). "Wireless LANs Complement Existing Corporate Networks," Computerworld.

Brodsky, Ira (1995, July). "Wireless world," Internet World, 6: 34-41.

Dao, Tien. (1996, July). "Networking in Vietnam," National Library of Australia News, 7 (10): 13-16.

Dennis, Nancy K., Carter, Christina E., and Bordeianu, Sever. (1997). "Vision vs. reality: Planning for the implementation of a Web-based online catalog in an academic library," Library Hi Tech, 15 (3-4): 159-171.

DiCarlo, Lisa. (1997, December 2). "Intel readies plans for simpler NCs." PC Week Online, p. 1.

http://www.zdnet.com/zdnn/content/pcwo/1202/252473.html

Gerding, David. (1998, February). "Net PCs: Less is more." PC Computing, pp. 1-3.

http: //www.zdnet.com/products/content pccg/1102/268079.html.

Hayes, Brian. (1997, May-June). "The infrastructure of the information infrastructure," American Scientist, 85: 214-218.

"Netnam: Online Service of VAREnet--Vietnam Academic Research Educational Network" Home Page (1998, February).

http://www.batin.com.vn/vninfo/netnam.htm#t3.

Saffady, William. (1997, March-April). "Vendors of integrated library systems for minicomputers and mainframes: An industry report, Part 1, Introduction." Library Technology Reports, 33: 131-139.