PHOTOGRAPHS

Ever since it became commercialized in the early 1860s,1 photography has enjoyed an intimate if ambivalent relationship with the performing arts. Dramatic actors, opera singers, and dancers were frequent subjects of cartes de visite, or small cardboard-mounted photographic prints measuring 4 by 2 ½ inches, and the supersession of “cartomania” by the slightly larger cabinet photograph (measuring 6 ½ by 4 ½ inches) in 1866 only intensified collectors’ desire for performers’ likenesses, which could now be captured and printed in greater detail.2 These photographic cards provide invaluable insight into actors’ physical features, costuming, and even characterization and posture, but as David Mayer emphasis, they are not documentation of live performance. They were “first and foremost” portraits, meant to publicize performers rather than plays, and usually taken in a portrait photographer’s studio.3 Long exposure times—eight seconds in the 1870s and 40 seconds by the 1900s—and poor lighting conditions made shooting within the theater cumbersome, and photography during stage performance wouldn’t become possible until after 1901.4 Even after electric lighting and more agile equipment made shooting during performance easier, carefully composed studio photographs persisted as a fixture of theater iconography.5

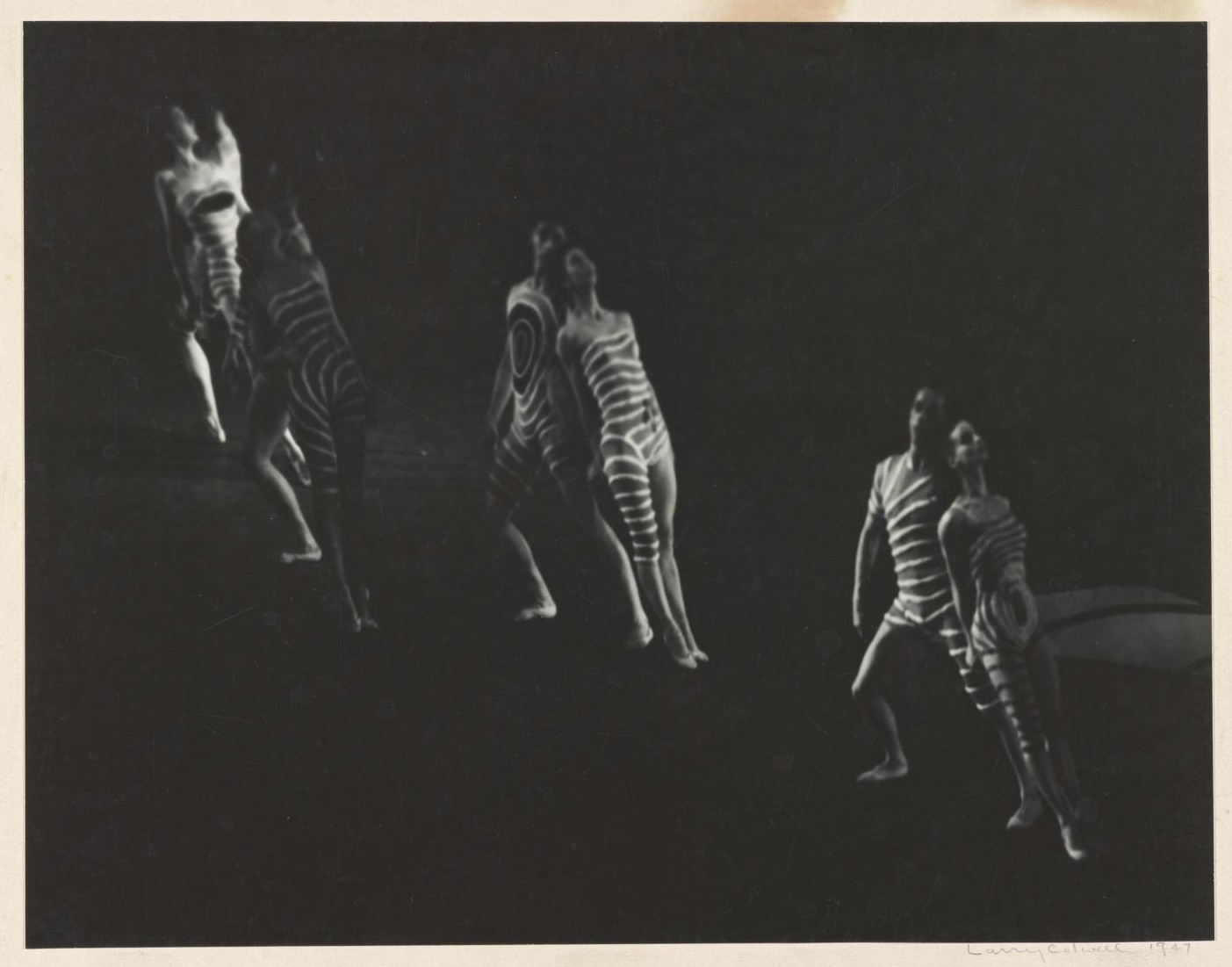

Photograph of The Seasons at the New York City Ballet, choreographed by Merce Cunningham, 1947,

Larry Colwell dance photographs, Library of Congress (free to use with proper citation)

Whether shooting from the back of the auditorium during performance actually provides a more accurate and authentic record than performance staged for the photographer’s camera is up to debate. A “photo-documentor” situated at the margins of the auditorium can visually capture the look of a performance in real time and under accurate lighting conditions, but their distance from the stage undermines their ability to capture the intimacy which individual audience members experience.6 The question of whether a still photograph could ever capture the dynamics of live performance is especially fraught in the field of dance, an art form defined by movement. On one hand, photography allows the viewer to see a gesture or configuration with greater clarity than they could watching the dance unfold in time.7 On the other, the stillness of the image cannot, by definition, represent movement.8

For theater and dance critics alike, the aesthetic and documentary value of a photograph is determined not so much by the circumstances of its creation (in a studio vs. a theatre, during rehearsal vs. before a live audience) but in how the photographer uses their medium to represent the narrative context and experiential dimensions of a single moment in time. For this reason, understanding theatre and dance photographs as documents requires looking at rather than through the idiosyncrasies of an individual photographer’s style and appreciating how pre- and postproduction interventions get the viewer closer to rather than further away from the “real” performance.9

General/interdisciplinary

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Bob Golby Collection, 1931-1977 (approx. 61 boxes and 560 oversize folders)Victoria & Albert Museum

Graham Brandon Theatre and Performance Photography collection, 1979-2003 (743 files)Theater

New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts

Joan Marcus photographs, 1980-2019 (340 boxes, 29.68 TB of digital files)Carol Rosegg photographs, 1978-2018 (481 boxes)

G. Maillard Kesslere photographs, 1925-1953 (approx. 41 boxes)

Avery Willard photographs, 1919-1993 [bulk 1940-1970] (approx. 73 boxes)

Robert Benney research materials, 1927-1978 (11 boxes)

Friedman-Abeles photographs, 1934-1991 [bulk 1954-1970]

New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Negro Actors Guild of America photograph collection, [190-]-[198-] (16 boxes)Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Theater Biography Collection, ca. 1750-2021 (867 boxes, mixed material)Production Photographs Collection, ca. 1860-1998 [bulk 1990-1965] (82 boxes)

Houghton Library, Harvard University

Harvard Theatre Collection cabinet photographs of scenes, ca. 1866-1929 (22 boxes)Harvard Theatre Collection of theatrical cabinet photographs of women, ca. 1866-1929 (310 boxes)

Harvard Theatre Collection of theatrical cabinet photographs of men, ca. 1866-1929 (155 boxes)

Harvard Theatre Collection of theatrical scene photographs, 1860-2010 (86 boxes and 109 oversize folders)

Harvard Theatre Collection of theatrical portrait photographs, ca. 1860-2010 [bulk 1880-1930] (474 boxes and 796 oversize folders)

Photographs of Broadway productions, ca. 1895-1940 (18 boxes)

Photographs of theatrical performers, 1862-1982 (15 boxes)

Alix Jeffry photographs, 1952-1974 (12 boxes)

Alix Jeffry additional papers, 1935-1994 (27 boxes and 1 folder)

Haas Arts Library, Yale University

Yale Rockefeller theatrical prints collection, 1934-1976 (103 boxes)Victoria & Albert Museum

Guy Little Collection, ca. 1860s-1900s (52 boxes)Ivan Kyncl Photographic Archive, 1984-2004 (90 boxes)

University of Bristol Theatre Collection

Mander & Mitchenson CollectionJohn Vickers Archive, 1845-1976 (ca. 8,000 photographic prints, 40,000 negatives, and 1,800 slides)

Dance

New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts

Photographic negatives of dancers and dance companies, 1941-1961 (29 boxes and 43,975 negatives)Kenn Duncan photograph archive, ca. 1960-1986 (approx. 390 boxes)

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater: Jack Mitchell photographs, ca. 1961-1992 (3 boxes)

Alfred Valente negatives, 1934-1958 (17 boxes)

Joanne Savio photographs, 1981-2006 (15 boxes)

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Fred Fehl Dance Collection, 1940-1985 (approx. 130 boxes)Houghton Library, Harvard University

Harvard Theatre Collection of dance organization photographs, ca. 1860-2010 (9 boxes)Harvard Theatre Collection of dance portrait photographs, ca. 1903-1990 (12 boxes)

Harvard Theatre Collection of dance scene photographs, ca. 1924-1989 (3 boxes and 31 oversize folders)

John Lindquist Collection, 1910-1985 (approx. 35 boxes and 31 albums)

Arks Smith papers, 1924-2022 (25 boxes)

Library of Congress

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Collection, 1910-1924 [bulk 1950-2005] (55 boxes of photographs)American Ballet Theater archive, 1940-2014 [bulk 1940-1992] (29 boxes of photographs)

Larry Cowell dance photographs, 1944-1966 (8 boxes)

David A. Fullard dance photographs, 1977-2012 (20 boxes and 632.55 GB of digital files)

Victoria & Albert Museum

Duncan Melvin photograph collection, ca. 1940s (23 boxes)Edward Mandinian photograph collection, ca. 1940s (1000 items)

Opera

New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts

Images of the New York City Opera, ca. 1940-1980 (3314 photographic prints, 3000 film negatives, etc.)Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Opera Collection, ca. 1800s-1990 [bulk 1880-1950] [no published finding aid; extent of photographic holdings unknown]Girvice Archer Jr. Opera Collection, late 18th-mid 20th centuries (104 boxes) [no published finding aid; primarily photographs and negatives]

Houghton Library, Harvard University

Harvard Theatre Collection of cartes-de-visite portrait photographs of female opera musicians, ca. 1854-1879 (6 boxes)Harvard Theatre Collection of cartes-de-visite portrait photographs of male opera musicians, ca. 1854-1879 (2 boxes)

Victoria & Albert Museum

Collection of Andrew Phillips Photographs, ca. 2000-2005 (ca. 12,000 digital photographs)Performance Art & Experimental Theater

New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts

Nathaniel Tileston photographs, 1964-2019 (36 boxes)John Edward Heys papers, 1962-2001 [bulk 1969-2000] (visual material scattered across 8 boxes)

Max Waldman photographs, 1959-2014 [bulk 1965-1981] (55 boxes of photographic materials; includes other subjects)

[2] Erin Pauwels, “The Art of Not Posing: Napoleon Sarony and the Popularization of Pictorial Photography,” Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography, ed. John Rohrbach (University of California Press, 2020), 28.

[3] David Mayer, “‘Quote the Words to Prompt the Attitudes’: The Victorian Performer, the Photographer, and the Photograph,” Theatre Survey 43:2 (November 2002): 227.

[4] Mayer, 227.

[5] Peter Buse, “Stage Remains: Theatre Criticism and the Photographic Archive,” Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism (Fall 1997): 82.

[6] Natalie Crohn Schmitt, “Recording the Theatre in Photographs,” Educational Theatre Journal 28:3 (October 1976): 386.

[7] Jenelle Porter, “Dance With Camera: A Curator’s POV,” The Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies, ed. Douglas Rosenberg (Oxford University Press, 2016), 23.

[8] Matthew Reason, “Still Moving: The Revelation or Representation of Dance in Still Photography,” Dance Research Journal 36 (2004): 49.

[9] Reason, 61, and Crohn Schmitt, 388.