SCRAPBOOKS

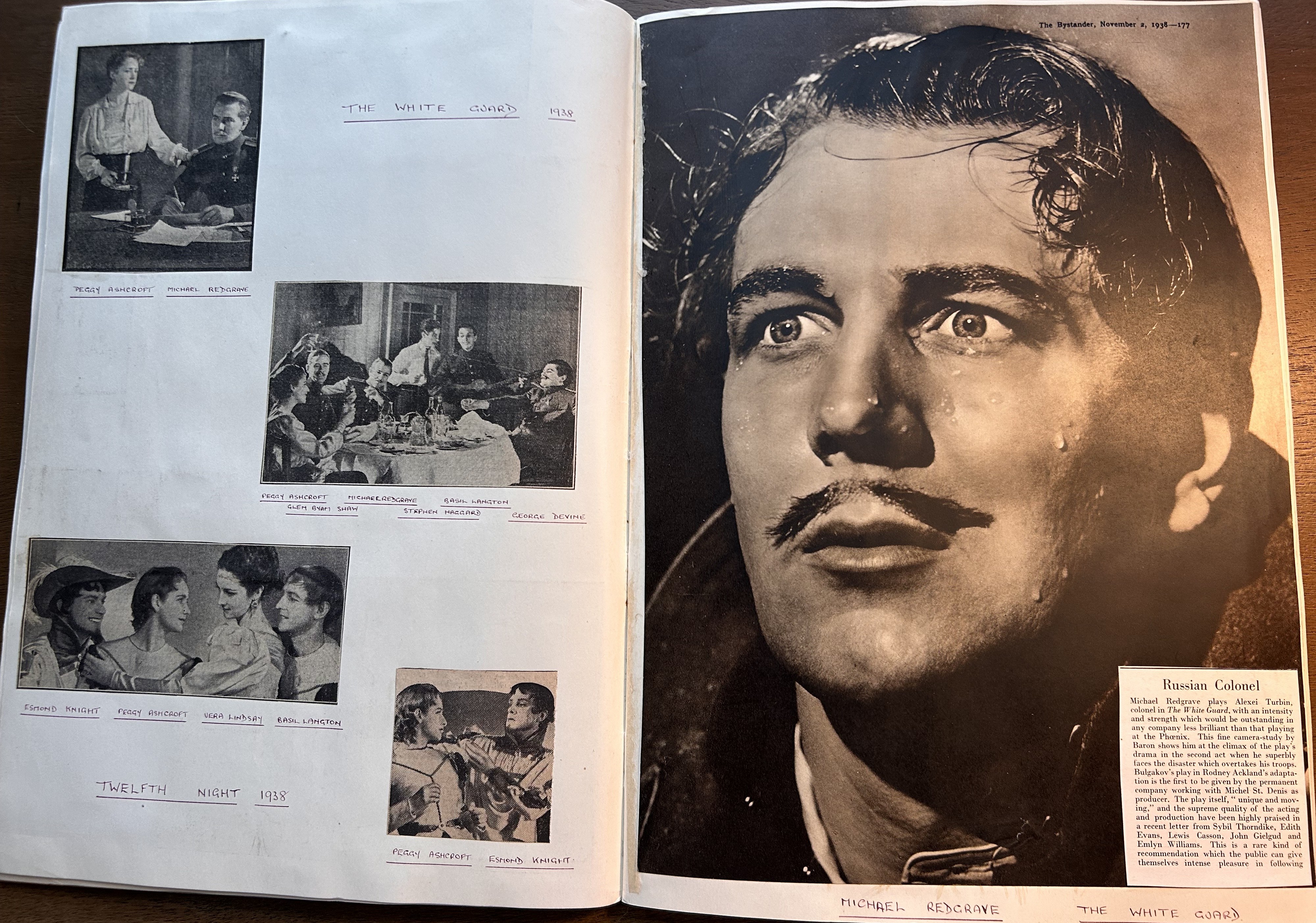

Theatrical scrapbooks exist because theatrical ephemera exists. The Oxford English Dictionary’s earliest entry for the word scrapbook dates to 1817,1 and by 1823, theatrical scrapbooks were apparently already a familiar genre, if newspaper column titles like “The Stage Scrap-book” are any indication.2 Early scrapbooks consist of the printed ephemera available to theatergoers, hobbyist historians, and actors at that time: newspapers and playbills. As new printing techniques and print formats emerged, so did they appear in scrapbooks. Folded programs—a product of the 1860s—would either have their casts lists clipped out or be carefully affixed in their entirety to scrapbook pages. Wood engravings reproduced in newspapers like the Illustrated London News in the 1840s allowed text-based ephemera to be supplemented with visual representations of actors and scenes,3 and the invention of halftone printing allowed photographs to be published in magazines like The Graphic and clipped for scrapbooking.4

Not every type of ephemera was, initially, suited for scrapbooking. The cardboard mountings of cartes de visite and cabinet photographs posed a challenge to pasting, and collectors generally opted to preserve them in specially manufactured albums made of thick pages with pre-cut windows into which photographs could be slipped. With the introduction of the thinner “picture postcard” at the turn of the century,5 photographic portraits could be easily placed directly alongside programs and tickets, and the flourishing of magazines during this same period further supplied compilers with graphic fodder for their pages.6 Sharon Marcus dates the “golden age” of the theatrical scrapbook to this period, 1880 to 1920,7 but the flood of fan magazines ushered in by Hollywood’s star system during the ‘20 and its imitation by the recording industry in the ‘50s and ‘60s ensured that the fan scrapbook would endure well into the final decades of the twentieth century, and thespians often shared space with screen idols and pop stars. And because programs continued to be an important part of the theatergoing experience across performing arts disciplines, scrapbooks continued to provide an effective medium for organizing and preserving one’s programs.

Scrapbook titled "Theatre," dated 1938-1939, of British provenance (webmaster's personal collection)

Fans weren’t the only participants in performance culture who created scrapbooks. Performers both famous and forgotten used the medium to track their career through clippings and programs, and annotations provide direct insight into their reflections on their work. Critics did so as well. Yet fan scrapbooks have the most scholarly interest because they document the least documented aspect of an already ephemeral art form, spectatorship. Scrapbooks that consist only of programs without any annotations indicate individual tastes and tendencies, while annotations—a common practice in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, when preprinted rubrics started to appear—provide direct insight into the compiler’s feelings and reactions. The careful clipping and arrangement of performers’ portraits showcase how compilers used the medium to bridge the gap between spectator and performer and deepen their intimacy with performers’ bodies.8

This latter practice has particular significance to researchers interested in spectatorship’s intersection with gender and sexuality. By the end of the nineteenth century, the British press heralded scrapbooking as the “latest fad” among young women,9 and the Weekly Irish Times singled out the theatrical scrapbook as “now considered a necessary possession by every theatre-going woman.”10 Scrapbooks could even preserve queer desires and pleasures, as Kim Marra argues of a four-volume scrapbook dedicated to Maude Adams—described by biographers as a lesbian11—lovingly compiled by the unmarried Phyllis Robbins, who made sure to include the program from the evening when she first met Adams.12

Theater

New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts

Harriet L. Lagowitz scrapbooks, 1879-1893 (9 volumes)Mrs. Harry A. Lee scrapbooks, 1849-1918 [bulk 1887-1915] (6 volumes)

Scrapbooks of Tallulah Bankhead and other actors, 1921-1968 (17 boxes)

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Scrapbook Collection, ca. 1738-1969 (262 bound volumes and 33 document boxes) [No published finding aid, but available for research]

Houghton Library, Harvard University

Theatrical scrapbook collection, 1791-1967 (114 boxes and 39 volumes)Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

Scrapbook File, Brander Matthews Dramatic Museum Ephemera, late 19th and 20th centuries (109 volumes)Theater Scrapbooks Collection, 1891-1949 (12 cartons)

Ohio State University Special Collections

Scrapbook Collection, 1866-1979 (112 boxes)Victoria & Albert Museum

Nancy Adam Bequest of Theatrical Notebooks and Scrapbooks, 1867-1950s (9 volumes)Miss P. Hall Theatrical Scrapbook Collection, 1944-1977 (5 volumes)

University of Bristol Theatre Collection

Mander & Mitchenson Collection (70 boxes and 101 volumes)Opera

New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts

Mrs. William Patten papers, 1801-1950 (22 boxes)[2] “The Stage Scrap-Book,” The Sun (December 22, 1823).

[3] "History of Periodical Illustration,” North Carolina State University, accessed December 9, 2025, https://ncna.dh.chass.ncsu.edu/imageanalytics/history.php.

[4] “Morgan, Inventor of Halftone, Dies,” The New York Times (August 31, 1941).

[5] Monica Cure, Picturing the Postcard: A New Media Crisis at the Turn of the Century (University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 28.

[6] Sharon Marcus, “The Theatrical Scrapbook,” Theatre Survey 54:2 (May 2013): 287-288.

[7] Marcus, 287.

[8] Marcus, 300-301.

[9] “An Up-To-Date Scrapbook,” The Dundee Courier (May 21, 1898).

[10] "Society Gossip,” Weekly Irish Times (September 8, 1900).

[11] Billy J. Harbin, Kim Marra, and Robert A. Schanke, The Gay & Lesbian Theatrical Legacy: A Biographical Dictionary of Major Figures (University of Michigan Press, 2007), 16-18.

[12] Kim Marra, “Phyllis Robbins (1883-1972),” The Routledge Anthology of Women’s Theatre Theory and Dramatic Criticism, eds. Catherine Burroughs and J. Ellen Gainor (Routledge, 2023), 165.