SCRIPTS

Of all the documents created during the production of a dramatic performance, scripts are most likely to be published—but not always. Many are only published in acting editions, and acting editions from before the 20th century are rarely (if ever) found in libraries’ circulating collections. In addition to early published scripts, national libraries such as the British Library and Library of Congress have large holdings of manuscript plays because they were submitted to the state either for a performance license from the censor (UK) or for copyright (US). Print and manuscript scripts provide an accurate record of dialogue and narrative, and the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays at the BL provide additional insight into the operations of the UK’s theatrical censor, with blue pencil marks bisecting lines requested to be omitted.

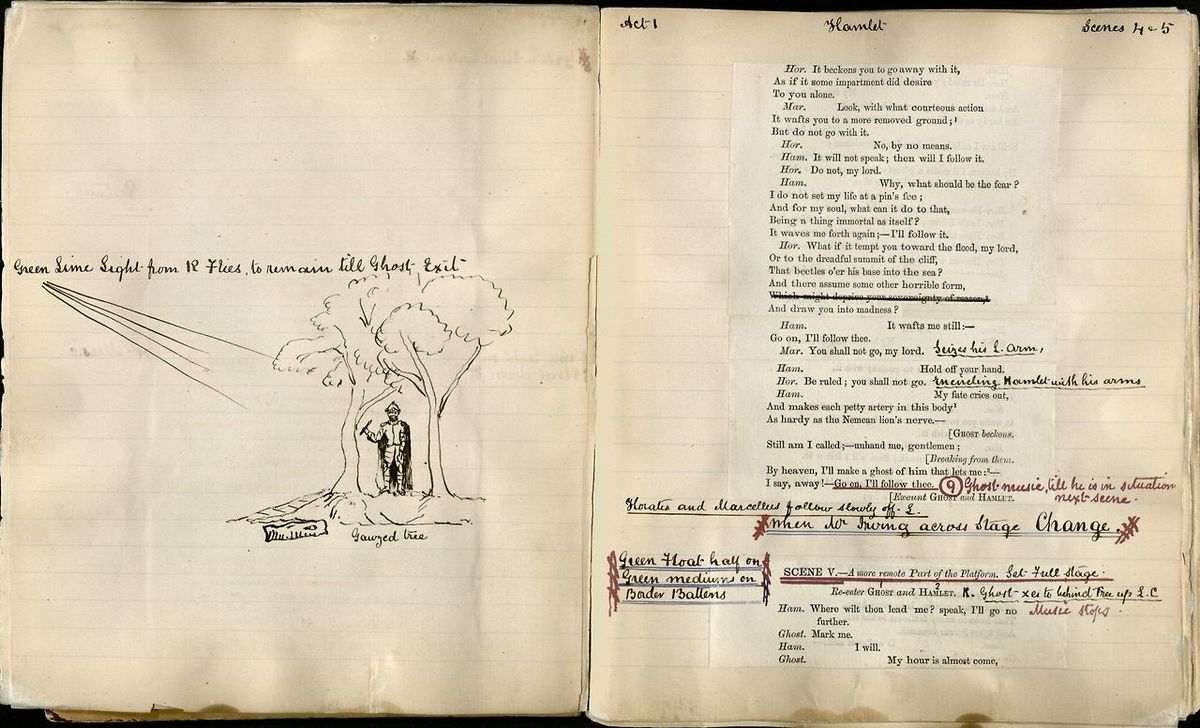

Prompt book for Henry Irving's 1874 production of Hamlet, Houghton Library, Harvard University (via Wikimedia Commons)

Prompt books tell us even more. Called “our best theatrical records of stage productions” by Edward A. Langhans,1 prompt books are working copies of the script kept by actors, the prompter (now known as stage manager) or technicians and function as instruction manuals for staging a performance. At the very least, annotations specify entrances and exits; often, they detail light and music cues, scenery shifts, and alterations to the script;2 and in some instances, they consist of the intricate blocking notations and diagrams which are now standard in stage management.3 Surviving prompt books date to the Medieval period and boast elaborate descriptions of onstage action and backstage technical processes, likely a reflection of the fact that stage management in Europe had yet to become a profession with its own vocabulary and shorthand.4 Prompt copies that look closer to what we would expect to find in a production today date to the Restoration and eighteenth century,5 and the wealth of surviving promptbooks owned by the nineteenth-century stage’s leading stars gives direct insight into how Shakespeare’s vaunted storytelling had to accommodate the demands of the star system.6

In the world of opera, the script’s equivalent is, of course, the libretto. The widespread use of surtitles in major opera houses has made reading a standard part of operagoing in recent decades, but the precedent for this practice reaches back for centuries. The libretti of early operas were published “far more often” than the musical scores,7 and because the darkened house wouldn’t become the norm until the end of the nineteenth century, audiences could follow along during the performance.8 Some composers, such as Verdi, even collaborated with publishers to make sure that the formatting of the text didn’t disrupt the spectator’s experience witnessing the drama unfold on stage.9 While the darkening of the auditorium prevented libretti reading for much of the 20th century, the increasing reliance on the operatic repertoire mitigated operagoers’ need to consult a transcription of an unfamiliar sung drama—though some spectators still arrived armed with a flashlight.10

Unlike drama and opera, dance has no standard written record, but a variety of notation systems have sought to transcribe dance on paper. Notations had traditionally focused on specifying dance steps and floor paths, but with the development of the ballet d’action during the eighteenth century, choreographers had to devise idiosyncratic systems for recording the entire body’s—not just the feet’s—movement in time.11 Nineteenth-century notation systems often used stick figures or modified music notes along with a musical staff to record the movements of different parts of the body.12 Only Rudolf von Laban’s system, devised in the 1920s, was widely adopted, and Labanotation was created to serve the needs not of ballet but modern dance, with specifications for weight, space, time, and flow rather than steps and gestures.13 The arrival of video in the 1970s and digital motion-capture tools (or “mocap”) in the 2000s has shifted the recording of movement away from paper-based systems.14 Because of the ability for instantaneous replay and, as technology developed, the ability to supplement visual data with annotations, video and motion capture are “analytical” as much as they are preservation tools, allowing choreographers and dancers to collaborate during the rehearsal process.15

Theater

New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts

Roger Belrind Productions collection of scripts, 1983-2013 (26 boxes and 2 volumes)Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Playscripts and Promptbooks Collection, 1795-1978 [bulk 1870-1915] (17 boxes)Houghton Library, Harvard University

British prompt book and theatrical manuscript collection, ca. 1680-2000 (12 boxes)Library of Congress

Manuscript Plays Collection, Library of Congress Copyright Office drama deposits, 1863-1973 [bulk 1890-1940] (190 containers)British Library

Lord Chamberlain's Plays [linked resource unavailable due to reconstruction of BL website]

University of Bristol Theatre Collection

Mander & Mitchenson Collection (165 boxes)Dance

Houghton Library, Harvard University

Nikolai Sergeev dance notations and music scores for ballets, 1888-1944 [bulk 1902-1931] (approx. 30 boxes)Library of Congress

Dance Notation Collection, 1893-1983 [bulk 1946-1992] (6 containers)American Ballet Theater archive, 1940-2014 [bulk 1940-1992] (25 boxes of dance notation from 1955-1980s)

Opera

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Hans Peter Kraus Collection of Libretti, 1600-early 20th century (approx. 3,800 items) [no published finding aid]Houghton Library, Harvard University

Opera librettos, 1838-2003 (14 boxes)[2] Edward A. Langhans, “Research Opportunities in Early Promptbooks,” Educational Theatre Journal 18:1 (March 1966): 74-75.

[3] Langhans, “Eighteenth-Century Promptbooks and Staging Practices,” 154.

[4] Langhans, “Eighteenth-Century Promptbooks and Staging Practices,” 131.

[5] Langhans, “Eighteenth-Century Promptbooks and Staging Practices,” 132.

[6] William G.B. Carson, “As You Like It and the Stars: Nineteenth-Century Prompt Books,” The Quarterly Journal of Speech 43:2 (April 1957): 118-120.

[7] Patrick Smith quoted in Lucile Desblache, “Music to my ears, but words to my eyes?,” Linguistica Antwerpiensa 6 (2007): 157.

[8] William Germano, “Reading at the Opera,” University of Toronto Quarterly 79:3 (Summer 2010): 891.

[9] Germano, 892.

[10] Desblache, 161-3.

[11] Claudia Jeschke and Robert Atwood, “Expanding Horizons: Techniques of Choreo-Graphy in Nineteenth Century Dance,” Dance Chronicle 29:2 (2006): 196.

[12] Claudia Jeschke, “Reflecting on time while moving: Dance notations from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century,” in Music-Dance: Sound and Motion in Contemporary Discourse, eds. Patrizia Veroli and Gianfranco Vinay (Routledge, 2018), 97-99.

[13] Mark Franko, “Writing for the Body: Notation, Reconstruction, and Reinvention in Dance,” Common Knowledge 17:2 (Spring 2011): 327.

[14] Franko, 330-332.

[15] Laura Karreman, “The Dance without the Dancer: Writing dance in digital scores,” Performance Research 18:5 (2013): 126.